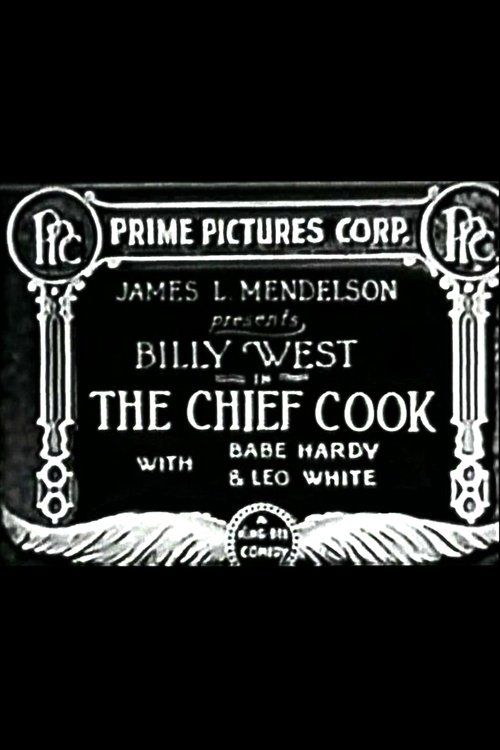

The Chief Cook

Plot

The Chief Cook opens in the lobby of a small hotel where the desk clerk and owner (Bud Ross) sternly addresses three staff members: the cook, the waiter, and the bellboy. The cook's reaction is particularly animated, with his flailing arms repeatedly knocking down the man behind him until all three servants dramatically quit in unison. They storm into the adjoining kitchen where they encounter a slavery maid (Blanche White) scrubbing the floor on her hands and knees. The men all trip over her, briefly moan in frustration, and then exit the kitchen, leaving the maid to continue her work. The film continues with comedic situations as the former employees attempt to find new employment while creating chaos wherever they go, eventually leading to a series of misunderstandings and physical comedy gags typical of silent era shorts.

About the Production

The Chief Cook was produced during the height of the silent comedy era when studios were churning out two-reel shorts at a rapid pace. Billy West, the star, was known for his Charlie Chaplin imitation and this film was part of a series of comedies he made for King Bee Studios. Oliver Hardy, who would later achieve worldwide fame as half of Laurel and Hardy, appears here in an early supporting role before his partnership with Stan Laurel began. The film was typical of the slapstick comedy style popular in 1917, featuring physical gags, exaggerated reactions, and fast-paced action sequences.

Historical Background

The Chief Cook was produced in 1917, a pivotal year in world history and American cinema. The United States had just entered World War I in April 1917, and films like this served as important escapist entertainment for audiences dealing with the uncertainty of wartime. The American film industry was consolidating its power in Hollywood, with studios developing efficient production systems to meet growing demand. Comedy was particularly popular during this period, with stars like Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd establishing themselves as major box office draws. Billy West's success as a Chaplin imitator reflected both Chaplin's immense popularity and the industry's tendency to create variations on successful formulas. The film industry was also transitioning from short subjects to feature-length productions, though comedy shorts remained a staple of theater programming throughout the silent era.

Why This Film Matters

The Chief Cook represents a typical example of the two-reel comedy format that dominated American cinema in the late 1910s. While not groundbreaking, it exemplifies the slapstick comedy style that would influence generations of comedians and filmmakers. The film also serves as an early showcase for Oliver Hardy before his iconic partnership with Stan Laurel, making it historically significant for comedy scholars. Billy West's career as a Chaplin imitator highlights the phenomenon of star imitation that was common in early Hollywood, when studios sought to capitalize on successful formulas. The film's depiction of hotel service workers reflects the class structure and workplace dynamics of the era, presented through the lens of comedy. As with many silent films, it provides a window into the visual storytelling techniques that filmmakers developed before the advent of synchronized sound.

Making Of

The production of The Chief Cook followed the factory-like efficiency common in Hollywood during the 1910s, with comedy shorts being produced in just a few days. Director Arvid E. Gillstrom worked with a regular troupe of comedy actors who understood the timing and physical requirements of slapstick humor. Billy West, who had developed his Chaplin-esque persona through years of vaudeville experience, would often improvise gags during filming. Oliver Hardy, still building his career before his legendary partnership with Stan Laurel, was developing the larger-than-life character traits that would later make him famous. The hotel set was likely a simple construction on a studio backlot, designed to maximize the potential for physical comedy with its confined spaces and multiple doorways. The film was shot in the standard 35mm format of the era, with intertitles providing the dialogue and narrative exposition.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Chief Cook was typical of comedy shorts from 1917, featuring static camera positions and wide shots that captured the full range of physical action. The camera work was functional rather than artistic, designed primarily to clearly present the slapstick gags without visual obstruction. The film likely used standard 35mm film stock with the orthochromatic process common to the era, which rendered colors in limited tones but was suitable for black and white comedy. Lighting was flat and even, prioritizing visibility over dramatic effect. The hotel set was designed to allow for clear sightlines and multiple entrances/exits to facilitate chase sequences and physical comedy routines.

Innovations

The Chief Cook did not feature any significant technical innovations, as comedy shorts of this era typically employed established techniques rather than experimenting with new technology. The film used standard editing practices of the period, including simple cuts and occasional iris shots for emphasis. The physical comedy effects were achieved practically through stunt work and timing rather than special effects. The film represents the refinement of existing comedy techniques rather than technical advancement, though its efficient production methods exemplified the industrialization of filmmaking that characterized Hollywood during this period.

Music

As a silent film, The Chief Cook was originally accompanied by live musical performances that varied by theater. Large urban theaters might have employed small orchestals to perform original scores or compiled classical pieces, while smaller venues typically used a pianist or organist. The music would have been synchronized to the on-screen action, with upbeat tempos for chase scenes and dramatic chords for moments of physical comedy. No original score survives, and modern screenings typically use period-appropriate compiled scores or newly composed music in the style of 1910s silent film accompaniment.

Famous Quotes

No dialogue quotes available - silent film with intertitles

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where the cook's animated arms repeatedly knock down the man behind him while the clerk is speaking, leading to the simultaneous resignation of all three employees

Did You Know?

- Billy West was one of the most famous Charlie Chaplin imitators of the silent era, even being mistaken for Chaplin by audiences in some markets

- Oliver Hardy was still using his birth name 'Oliver Hardy' in this film, though he would sometimes be credited as 'Babe Hardy' in later works

- Director Arvid E. Gillstrom was a Swedish-born director who specialized in comedy shorts and worked frequently with both Billy West and Harold Lloyd

- The film was released just as the United States was entering World War I, reflecting the escapist entertainment audiences sought during wartime

- King Bee Studios was a short-lived production company that existed primarily to capitalize on Billy West's Chaplin-like popularity

- The character of the slavery maid played by Blanche White reflects the unfortunate racial stereotypes common in films of this era

- This was one of over 40 short comedies Billy West made between 1916 and 1921

- The film's title refers to the cook character, though the story actually follows multiple hotel employees

- Silent films of this period were typically accompanied by live musical scores that varied by theater and performance

- The physical comedy style in this film influenced later slapstick comedians, including The Three Stooges

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of The Chief Cook were generally positive within the context of comedy short reviews of the era. Trade publications like Variety and The Moving Picture World typically praised the film's physical comedy gags and the performances of its cast, particularly noting Billy West's Chaplin-esque antics. Modern critics and film historians view the film primarily as a historical artifact, valuable for its early appearance of Oliver Hardy and its representation of the slapstick comedy genre. While not considered a masterpiece of silent comedy, it is recognized as a competent example of its type and an important piece of comedy history. The film is often discussed in studies of Chaplin imitators and the development of American slapstick comedy.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1917 generally responded positively to The Chief Cook, as it delivered the kind of fast-paced physical comedy they expected from comedy shorts. Billy West's popularity as a Chaplin-like figure ensured good attendance for his films, though some audiences were reportedly confused about whether they were watching the real Chaplin. The film's simple plot and visual gags made it accessible to diverse audiences, including recent immigrants who might struggle with English intertitles. Modern audiences encountering the film through screenings at silent film festivals or archival collections typically appreciate it for its historical value and the opportunity to see a young Oliver Hardy before his fame.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Charlie Chaplin films

- Mack Sennett comedies

- Keystone Cops style

This Film Influenced

- Later hotel comedies

- Workplace comedy shorts of the 1920s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of The Chief Cook is unclear, but like many silent shorts from this period, it may be partially or completely lost. Some fragments or copies might exist in film archives such as the Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art, or private collections. The survival rate for silent films is estimated at around 25%, with comedy shorts having a particularly low survival rate due to their perceived disposability at the time of production. Any surviving copies would likely be on 35mm nitrate film requiring careful preservation and potentially digital restoration.