The Daughter of Dawn

Plot

The Daughter of Dawn tells the story of Dawn, a Kiowa woman caught between two suitors: the brave warrior Black Wolf and the jealous rival Red Wing. After Black Wolf proves his valor through impressive feats including a dramatic buffalo hunt and battles with Comanche warriors, Dawn chooses him as her mate. The narrative explores themes of love, honor, and tribal tradition while showcasing authentic Kiowa and Comanche culture, ceremonies, and daily life. The film culminates in dramatic confrontations that test the lovers' commitment and the strength of their community bonds, all set against the sweeping landscapes of the Oklahoma territory.

About the Production

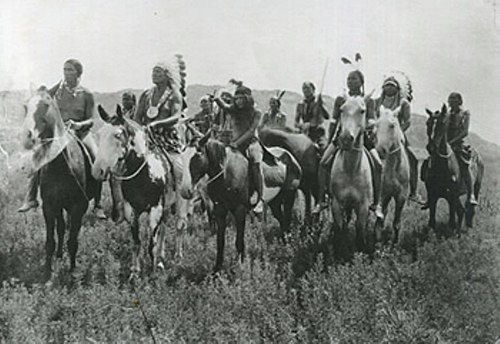

Filmed entirely on location with an authentic Native American cast recruited from Kiowa and Comanche reservations. The production was granted unprecedented access to film actual tribal ceremonies and gatherings. Director Norbert A. Myles worked closely with tribal elders to ensure cultural accuracy. The cast performed their own stunts and traditional rituals authentically on screen. White Parker, the male lead, was the son of Quanah Parker, the last chief of the Comanche tribe.

Historical Background

The film emerged during the height of the silent film era when Hollywood typically portrayed Native Americans through stereotypes and white actors in redface. The early 1920s saw Native American communities grappling with the aftermath of forced assimilation policies, the loss of traditional lands, and pressure to abandon their cultural heritage. Oklahoma, where the film was made, had only achieved statehood in 1907, dramatically altering tribal sovereignty and traditional ways of life. This period also saw the rise of the Indian Boarding School system, which actively worked to erase Native American culture. Against this backdrop of cultural suppression, 'The Daughter of Dawn' represented a rare opportunity for Native Americans to present their own stories and traditions authentically, preserving cultural practices that were actively being threatened by government policies.

Why This Film Matters

This film stands as a groundbreaking artifact in American cinema history, representing one of the earliest examples of Native Americans controlling their own narrative on screen. Unlike typical Hollywood Westerns that portrayed Native peoples as obstacles to progress or savage stereotypes, this film presents an intimate, authentic view of Kiowa and Comanche life, traditions, and values. The film serves as an invaluable time capsule of Native American culture at a critical historical moment when many traditions were being lost to assimilation. Its restoration has allowed modern scholars and audiences to study authentic representations of tribal ceremonies, clothing, and social structures from the period. The film challenges the dominant narrative of early American cinema and provides evidence that Native Americans were actively involved in filmmaking from its earliest days, even when their contributions were marginalized by the mainstream industry.

Making Of

Director Norbert A. Myles, a relatively obscure filmmaker working with the Texas Film Company, undertook an ambitious project that was revolutionary for its time. Instead of following Hollywood's practice of casting white actors in redface, Myles recruited actual Kiowa and Comanche tribal members from Oklahoma reservations. The production faced numerous challenges, including coordinating with tribal elders for permission to film sacred ceremonies and working in remote locations without modern equipment. Many tribal members were initially skeptical but became enthusiastic participants when they realized the film would authentically represent their culture. The buffalo hunt scenes were particularly challenging, requiring coordination of multiple riders and ensuring safety while maintaining authenticity. The production took place during a transitional period when many Native Americans were being pressured to abandon traditional ways, making the film's preservation of these customs particularly significant.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Robert E. Smith captures the majestic beauty of the Wichita Mountains with sweeping wide shots that emphasize the connection between the Native characters and their ancestral lands. The camera work, while typical of silent era techniques in its static compositions and dramatic intertitles, benefits enormously from the authentic outdoor locations rather than studio backdrops. Many scenes were filmed during actual tribal gatherings, giving the footage a documentary-like quality that was revolutionary for narrative films of the period. The use of natural lighting creates a warm, organic feel that enhances the authenticity of the performances. The buffalo hunt sequences demonstrate remarkable technical skill in capturing action on horseback, while the ceremonial scenes preserve visual records of tribal regalia and rituals with remarkable clarity.

Innovations

While not technically innovative in terms of cinematic techniques, the film's primary achievement lies in its authentic casting and location filming approach, which was revolutionary for 1920. The use of actual Native American performers rather than white actors in makeup set a precedent for authentic representation that would rarely be matched in mainstream cinema for decades. The film's survival and restoration after 85 years represents a major technical achievement in film preservation, requiring careful transfer from deteriorating nitrate stock, digital cleaning, and frame-by-frame restoration. The restoration team successfully preserved the original tints and toning effects used in the 1920 release, maintaining the film's original aesthetic intentions. The project also pioneered new techniques for restoring ethnographic films while respecting their cultural context and consulting with descendant communities.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Daughter of Dawn' originally would have been accompanied by live musical performances during screenings, likely featuring local musicians or theater organists. For its 2012 restoration, the Oklahoma Historical Society commissioned an original score by acclaimed composer Mark Isham that incorporates traditional Native American instruments, including flutes and drums, alongside orchestral elements. Isham's score respects the film's cultural origins while creating an emotional bridge for modern audiences. The soundtrack features authentic Kiowa and Comanche musical motifs recorded with tribal musicians, ensuring cultural accuracy. Some special screenings have featured live performances of the score, recreating the original silent era experience with contemporary musical sensitivity to the film's cultural significance.

Famous Quotes

When the moon is full, the warriors gather for the council

Love is stronger than the arrow of the enemy

A brave heart fears no darkness

The spirit of our ancestors walks with us

In the land of the rising sun, our people will endure

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic buffalo hunt sequence featuring authentic hunting techniques on horseback

- Tribal council scenes showing traditional Kiowa governance and decision-making

- Romantic moments between Dawn and Black Wolf set against Wichita Mountains sunsets

- Ceremonial dance sequences preserving actual tribal rituals and regalia

- Battle sequences with Comanche warriors demonstrating traditional warfare tactics

Did You Know?

- Featured an entirely Native American cast, extremely rare for the silent era when white actors typically played Native roles

- White Parker (male lead) was the son of Quanah Parker, the last chief of the Comanche tribe

- Wanada Parker (cast member) was also a descendant of Quanah Parker

- Considered lost for over 80 years until five complete reels were discovered in a private collector's basement in 2005

- The Oklahoma Historical Society spent $200,000 to restore the film

- Filmed on sacred Kiowa and Comanche land in the Wichita Mountains

- Many scenes were shot during actual tribal ceremonies and gatherings

- The cast performed their own stunts and traditional ceremonies authentically

- Only screened a handful of times before disappearing, contributing to its lost status

- The restoration premiered at the deadCENTER Film Festival in Oklahoma City in 2012

What Critics Said

Upon its limited 1920 release, the film received little attention from mainstream critics due to its restricted distribution and independent status. However, contemporary reviews in local newspapers praised its authenticity and the natural performances of the Native American cast. After its 2012 restoration, critics and film historians have universally acclaimed the film's cultural and historical importance. The New York Times called it 'a remarkable discovery that challenges our understanding of early American cinema,' while Variety noted its 'unprecedented authenticity and visual poetry.' Film preservation experts have hailed the restoration as a triumph, and the film has been featured in major film festivals and museum retrospectives celebrating its significance as both an artistic work and cultural document.

What Audiences Thought

Original 1920 audiences who attended the limited screenings reportedly were fascinated by the film's authentic portrayal of Native American life and the sweeping Oklahoma landscapes. Modern audiences who have experienced the restored version have expressed awe at seeing such rare footage of authentic tribal ceremonies and traditions. The film now serves as an educational tool, with screenings often accompanied by discussions about Native American representation in media. Many Native American viewers have expressed emotional responses to seeing their ancestors and cultural practices preserved on film, describing it as a connection to their heritage that was thought lost forever. The film has developed a cult following among film enthusiasts and has become required viewing in courses on Native American cinema and film history.

Awards & Recognition

- National Film Registry selection (2013) - Library of Congress

- Oklahoma Historical Society's Heritage Preservation Award (2012)

- Film Preservation Society's Restoration Excellence Award (2013)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Early ethnographic documentaries

- D.W. Griffith's 'The Red Man's View' (1909)

- Cecil B. DeMille's 'The Squaw Man' (1914)

- Edward S. Curtis's documentary work

- Contemporary interest in authentic Western stories

This Film Influenced

- Modern Native American cinema movements

- Smoke Signals (1998)

- Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (2001)

- Contemporary discussions about authentic casting

- Academic studies of early Native American representation

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for over 80 years until five complete nitrate reels were discovered in a private collection in 2005. The Oklahoma Historical Society undertook a comprehensive restoration project completed in 2012, involving frame-by-frame digital restoration, preservation of original tints, and creation of new preservation elements. The restored version has been added to the National Film Registry in 2013, ensuring its long-term preservation. The restoration represents one of the most significant film recovery projects of the 21st century, saving a unique piece of both American cinema history and Native American cultural heritage.