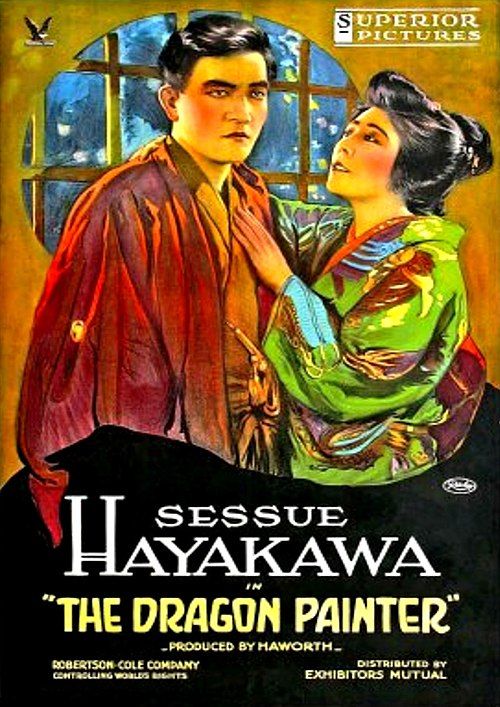

The Dragon Painter

"A Story of Art and Love in Old Japan"

Plot

Tatsu, a wild and reclusive young man living in the mountains of Japan, possesses an extraordinary divine gift for painting dragons that appear to come alive on his canvases. When master painter Kano Indara discovers Tatsu's remarkable talent, he brings him to his studio as a disciple, hoping to nurture his genius. Tatsu falls in love with Kano's daughter Ume-ko, but as his heart opens to human connection, his divine artistic ability mysteriously begins to fade. Struggling between his love for Ume-ko and his artistic gift, Tatsu descends into madness, believing his beloved has been transformed into a dragon. The film culminates in a dramatic confrontation where Tatsu must choose between earthly love and artistic transcendence, ultimately finding a way to reconcile his passion with his talent.

Director

About the Production

The film was produced by Sessue Hayakawa's own production company, Haworth Pictures, which he formed after becoming one of the highest-paid actors in Hollywood. The mountain scenes were filmed on location in Yosemite National Park, providing authentic and stunning backdrops that contrasted with typical studio productions of the era. The production faced challenges in finding appropriate locations that could stand in for the Japanese mountains, but the Yosemite locations proved exceptionally effective. Hayakawa insisted on authentic Japanese cultural elements throughout the production, including traditional costumes, customs, and artistic techniques depicted in the film.

Historical Background

The Dragon Painter was produced in 1919, a pivotal year in world history marking the end of World War I and the beginning of the Roaring Twenties. This period saw significant social change and technological advancement, including the maturation of the film industry from its primitive beginnings to a sophisticated art form. The film emerged during a time of heightened interest in Asian culture in the West, partly due to increased global interaction during the war years. However, this interest often manifested in exoticized and stereotypical portrayals in popular media. Hayakawa's production company represented a rare instance of authentic Asian representation in early Hollywood. The film was also created during the era of silent cinema, just before the transition to sound pictures would revolutionize the industry. The post-war period saw a surge in international film distribution, and The Dragon Painter was notable for its cross-cultural appeal and respectful treatment of its subject matter.

Why This Film Matters

The Dragon Painter holds immense cultural significance as one of the earliest Hollywood films to present Asian characters and culture with dignity and authenticity. At a time when Asian actors were typically relegated to villainous or comic relief roles, often played by white actors in yellowface, this film starred Sessue Hayakawa, one of the first true Asian-American movie stars, in a complex, sympathetic leading role. The film challenged prevailing stereotypes by presenting a nuanced exploration of Japanese artistic traditions and cultural values. Its success demonstrated that audiences would embrace authentic cultural stories when told with respect and artistry. The film also represents an important chapter in the history of Asian-American representation in media, showing early attempts at cultural self-determination in filmmaking. The preservation and restoration of The Dragon Painter has allowed modern scholars and audiences to study this rare example of early 20th century cross-cultural cinematic collaboration, making it an invaluable artifact for understanding both film history and the evolution of cultural representation in American media.

Making Of

The production of The Dragon Painter was remarkable for its time due to Sessue Hayakawa's unprecedented level of creative control as both star and producer through his Haworth Pictures Corporation. Hayakawa, who had become frustrated with the stereotypical roles typically offered to Asian actors, used his production company to create more authentic and respectful portrayals of Japanese culture. The filming in Yosemite National Park was ambitious for 1919, requiring the cast and crew to transport equipment to remote locations. Hayakawa and Aoki's off-screen relationship added authenticity to their on-screen chemistry. The production team consulted with Japanese cultural experts to ensure accuracy in depicting traditional arts, customs, and settings. The painting scenes required extensive rehearsal, with Hayakawa studying traditional Japanese brush techniques for months to convincingly portray a master artist. The film's success demonstrated the commercial viability of stories featuring Asian protagonists played by Asian actors, challenging Hollywood's prevailing practices of yellowface casting.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Dragon Painter, credited to Frank D. Williams, was highly praised for its artistic composition and effective use of natural landscapes. The Yosemite filming locations provided breathtaking mountain scenery that enhanced the film's mystical atmosphere. Williams employed innovative techniques for the time, including dramatic lighting effects to emphasize the supernatural elements of Tatsu's artistic gift. The painting sequences featured carefully composed close-ups that highlighted the brushwork and artistic process. The contrast between the wild mountain landscapes and the controlled environment of the master painter's studio was visually emphasized through composition and lighting. The film used tinting techniques to enhance emotional moments, with blue tones for night scenes and amber for warm, intimate moments. The cinematography successfully captured the essence of traditional Japanese aesthetic principles, including asymmetrical composition and attention to natural beauty.

Innovations

The Dragon Painter demonstrated several technical achievements for its 1919 production period. The location filming in Yosemite represented an ambitious undertaking, requiring portable equipment and challenging logistics for the era. The film's special effects, particularly the sequences suggesting the supernatural quality of Tatsu's paintings, utilized innovative double exposure techniques that were cutting-edge for the time. The production's attention to authentic Japanese art techniques required the development of new methods for filming painting sequences that could clearly show the brushwork and artistic process. The film's preservation and restoration in the 21st century utilized advanced digital techniques to stabilize and enhance the surviving film elements, making this century-old film accessible to modern audiences. The restoration process involved frame-by-frame digital cleaning and color tinting restoration based on original distribution materials.

Music

As a silent film, The Dragon Painter would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The score would typically have been provided by a theater's organist or pianist, often using compiled classical pieces or theater-provided cue sheets. For the film's restoration and modern screenings, new musical scores have been composed. Notably, the 2018 restoration by the George Eastman Museum featured a newly commissioned score by composer Stephen Horne, who incorporated traditional Japanese musical elements and instruments to complement the film's cultural setting. The modern scores aim to enhance the emotional journey of the characters while respecting the film's period and cultural context. The use of traditional Japanese scales and instrumentation in contemporary scores helps bridge the gap between the film's historical setting and modern audience expectations.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, The Dragon Painter featured intertitles rather than spoken dialogue. Key intertitles included: 'His brush was guided by the gods themselves,' 'Love had entered his heart, but the gods had departed from his art,' and 'In madness, he saw the truth of his soul.'

Contemporary reviews quoted the film's artistic message: 'The greatest art comes from the greatest suffering,' reflecting the film's central theme about the relationship between emotion and creativity.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Tatsu in his mountain wildness, painting dragons with supernatural intensity, establishing both his character and his divine gift.

- The first meeting between Tatsu and Ume-ko, where the wild artist is captivated by human beauty for the first time, foreshadowing his artistic crisis.

- The climactic scene where Tatsu, believing Ume-ko has transformed into a dragon, attempts to paint her back to human form, blending madness, love, and artistic desperation.

- The final reconciliation scene where Tatsu learns to balance his earthly love with his artistic gift, finding harmony between human emotion and divine inspiration.

Did You Know?

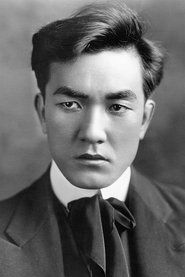

- Sessue Hayakawa was one of the first Asian-American movie stars and the highest-paid actor of his era, earning over $5,000 per week in 1919.

- The film was considered lost for decades before a print was discovered in the 1970s and subsequently preserved by the George Eastman Museum.

- Tsuru Aoki, who played Ume-ko, was Sessue Hayakawa's real-life wife, and they frequently appeared together in films.

- The Dragon Painter was one of the first Hollywood films to present a sympathetic, non-stereotypical portrayal of Asian characters and culture.

- The film was based on a story by Mary McNeil Fenollosa, who was deeply interested in Japanese culture and had lived in Japan.

- Director William Worthington was a former actor who transitioned to directing and worked frequently with Hayakawa.

- The painting sequences were carefully choreographed to show authentic Japanese brush techniques, with Hayakawa receiving training in traditional Japanese art.

- The film was a critical and commercial success, particularly praised for its artistic merit and respectful treatment of Japanese culture.

- The original story was adapted from a Japanese legend about the relationship between artistic genius and human emotion.

- The film's success led to Hayakawa forming his own production company to maintain creative control over projects featuring Asian themes.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised The Dragon Painter for its artistic merit, beautiful cinematography, and respectful treatment of Japanese culture. The New York Times lauded the film's 'exquisite photography' and 'powerful performances,' particularly noting Hayakawa's 'intense and moving portrayal.' Variety called it 'a picture of unusual artistic quality' that 'treats its Japanese subject with rare sympathy and understanding.' Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a groundbreaking work in Asian-American cinema history. Film historian Cari Beauchamp has described it as 'remarkably ahead of its time in its cultural sensitivity.' The film is now studied in film schools as an example of early authentic multicultural representation and has been featured in retrospectives at major film festivals including the San Francisco Silent Film Festival and the Pordenone Silent Film Festival.

What Audiences Thought

The Dragon Painter was well-received by audiences upon its release in 1919, particularly attracting viewers interested in artistic and cultural themes. The film's success at the box office helped establish Hayakawa's Haworth Pictures Corporation as a viable independent production company. Contemporary audience reviews in trade publications noted the film's emotional power and visual beauty. Modern audiences viewing the restored version have responded positively to the film's artistic qualities and its historical significance as an early example of authentic Asian representation in Hollywood. The film has developed a cult following among silent film enthusiasts and scholars of Asian-American cinema, with screenings at revival festivals often drawing enthusiastic crowds. Online film databases show consistently high ratings from viewers who appreciate the film's artistic merits and historical importance.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Traditional Japanese folklore and legends about artists

- Mary McNeil Fenollosa's studies of Japanese culture and art

- Contemporary Japanese art films being produced in the early 20th century

- The growing interest in Asian aesthetics in Western art and literature

This Film Influenced

- Later films featuring Asian-American protagonists in leading roles

- Subsequent films about artists and the creative process

- Modern works exploring authentic Asian representation in Western media

- Silent film restorations that prioritize cultural authenticity

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Dragon Painter was considered a lost film for several decades before a 35mm nitrate print was discovered in the 1970s. The film has since been preserved by the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York, which holds the most complete surviving elements. A major restoration was completed in 2018, utilizing digital technology to stabilize and enhance the surviving footage while preserving the film's original character. The restored version includes recreated color tints based on original distribution materials. The film is now considered one of the best-preserved examples of Sessue Hayakawa's work from this period and is regularly screened at silent film festivals and cinematheques worldwide.