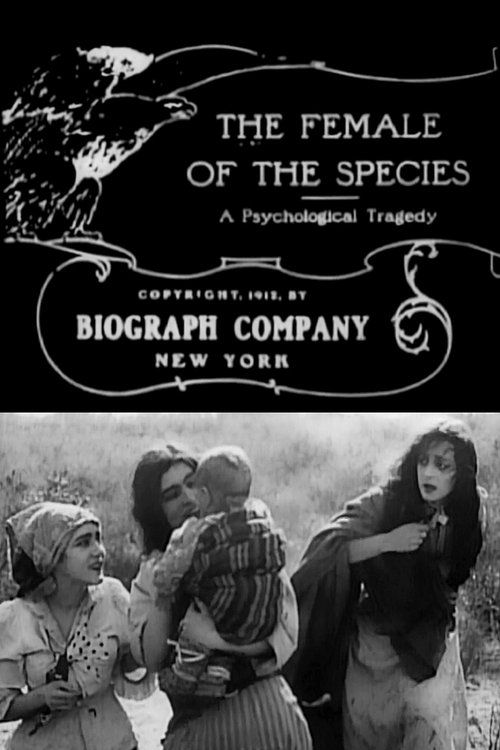

The Female of the Species

Plot

In this gripping silent drama, a group of survivors including a man and three women abandon their dying mining town and embark on a perilous journey across the harsh desert landscape. As they struggle against the elements and dwindling supplies, tensions rise among the travelers, particularly between the man's wife and her female companion. When the man succumbs to the brutal conditions during their trek, his wife becomes consumed by suspicion and jealousy, convinced that her companion had an affair with her deceased husband. The film culminates in a dramatic confrontation as the grieving wife plots her revenge, exploring the raw emotions and primal instincts that emerge when civilization's constraints are stripped away.

Director

About the Production

Filmed in the early days of cinema when Biograph was experimenting with longer narratives. The desert scenes were particularly challenging to shoot, requiring the cast and crew to endure actual harsh conditions. Griffith was known for his insistence on authentic locations, which added to the film's realism but also increased production difficulties.

Historical Background

1912 was a pivotal year in American cinema, marking the transition from short novelty films to more sophisticated narrative features. The film industry was still largely centered in New York, with California just emerging as a production hub. D.W. Griffith was at the height of his Biograph period, rapidly developing cinematic techniques that would define film language. This was the year before Griffith would make his controversial masterpiece 'The Birth of a Nation' and leave Biograph for Reliance-Majestic. The film reflected changing social attitudes about women's roles and psychology, as the suffrage movement gained momentum across America. The title's reference to Kipling's poem tapped into contemporary literary culture, showing cinema's growing ambition to be taken as seriously as literature and theater.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important milestone in the development of psychological drama in American cinema. Griffith's exploration of female jealousy and revenge was groundbreaking for its time, offering a complex portrayal of women's emotions beyond the simplistic characterizations common in early films. The film's title and themes contributed to early cinema's engagement with contemporary literary and scientific ideas about gender and psychology. Its survival and preservation make it an invaluable document of Griffith's developing style before his more famous epics. The film also demonstrates the early star power of Mary Pickford and her ability to carry dramatic weight, foreshadowing her future status as 'America's Sweetheart' and one of the most powerful women in Hollywood.

Making Of

The production of 'The Female of the Species' exemplified D.W. Griffith's growing ambition as a filmmaker. He pushed Biograph to allow him to film on location in the California desert, which was both expensive and logistically challenging for 1912. The cast had to endure genuine heat and harsh conditions during shooting, which contributed to the authentic feel of their suffering on screen. Mary Pickford, already becoming a major star, was given a more complex role than typical for the era, allowing her to showcase her dramatic range beyond the sweet ingenue parts she was known for. Griffith was experimenting with longer takes and more subtle acting styles, moving away from the exaggerated gestures common in early cinema. The film's darker themes initially caused concern at Biograph, with executives worried about audience reception to such a grim story, but Griffith's growing reputation gave him the leverage to see the project through.

Visual Style

The cinematography, credited to Billy Bitzer (Griffith's regular cameraman), was notable for its use of natural light in the desert sequences, which was unusual for 1912. The film employed wide shots to emphasize the vastness and isolation of the desert landscape, using the environment to mirror the characters' emotional states. Bitzer experimented with camera placement to create dramatic tension, particularly in the confrontation scenes. The harsh desert lighting created stark contrasts that enhanced the film's grim atmosphere. The interior scenes used more traditional lighting but incorporated subtle shadows to suggest psychological depth.

Innovations

The film demonstrated several technical innovations for its time, including the effective use of location shooting to enhance narrative impact. Griffith's blocking of actors in the wide desert shots showed an understanding of how to use space dramatically. The film's pacing, building tension through the journey across the desert, represented a sophisticated approach to narrative structure. The editing techniques, particularly the cross-cutting between the suffering characters and their memories or suspicions, showed Griffith's developing mastery of cinematic language. The film's relatively long running time for a Biograph production (a full reel) allowed for more character development than typical shorts of the era.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The typical score would have been compiled from classical pieces and popular songs of the era, with theater organists or pianists selecting music to match the mood of each scene. For dramatic moments, pieces by composers like Chopin or Beethoven might have been used, while the desert scenes might have been accompanied by more exotic or mysterious-sounding selections. No specific original score was composed for the film, which was standard practice for Biograph productions of this period.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue, but intertitles included: 'The female of the species is more deadly than the male' - Kipling quote)

'In the desert, civilization wears thin... and human nature shows its true face.'

'Jealousy is a poison that grows in the heart of the abandoned.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the abandoned mining town, establishing the desolate setting

- The desert journey with the characters struggling against the elements

- The death scene of the husband, filmed with surprising subtlety for the period

- The climactic confrontation between the two women, using minimal intertitles to convey the psychological tension

- The final shots of the lone survivor walking into the vast desert, emphasizing the film's themes of isolation and consequence

Did You Know?

- The title comes from Rudyard Kipling's famous poem 'The Female of the Species,' which includes the line 'The female of the species is more deadly than the male'

- This was one of Mary Pickford's last films for Biograph before she became an independent contractor and eventually co-founded United Artists

- The film was part of D.W. Griffith's exploration of more complex psychological themes in cinema, moving away from simpler melodramas

- Biograph refused to release the film initially, finding it too dark and controversial, but Griffith insisted on its distribution

- The desert scenes were filmed on location in California, a relatively uncommon practice for 1912 films which were typically shot entirely on studio sets

- This film is considered an early example of Griffith's use of landscape as a character in the narrative

- The original negative was destroyed in a Biograph vault fire in the 1920s, but copies survived through distribution prints

- Claire McDowell and Charles West were regular collaborators with Griffith, appearing in dozens of his Biograph films

- The film's exploration of female jealousy and revenge was considered quite daring for its time

- This was one of the first films to depict a purely female-driven conflict without male intervention in the climax

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews praised the film's dramatic intensity and the performances, particularly noting Mary Pickford's departure from her usual lighthearted roles. The Moving Picture World called it 'a powerful study of human emotion under extreme conditions' and praised Griffith's direction. Modern critics view the film as an important stepping stone in Griffith's development toward his more ambitious features. Film historians appreciate its relatively sophisticated psychological elements for the period and its role in establishing conventions of the desert survival genre. The film is often cited in scholarly works about early American cinema and Griffith's Biograph period as evidence of his growing mastery of cinematic storytelling.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1912 responded positively to the film's dramatic tension and the novelty of its desert setting. The more serious tone and psychological depth distinguished it from many contemporary films, which were often simpler melodramas or comedies. The film's exploration of darker themes was noted in viewer letters to trade papers, with some finding it refreshingly sophisticated while others found it disturbing. Mary Pickford's growing popularity undoubtedly contributed to the film's success at the box office. Modern audiences who have seen the film through archives and special screenings often express surprise at its relative sophistication for such an early production.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Rudyard Kipling's poetry (particularly 'The Female of the Species')

- Naturalist literature of the late 19th century

- Earlier Biograph dramas exploring psychological themes

- Contemporary stage plays dealing with psychological drama

This Film Influenced

- Later desert survival films

- Psychological dramas focusing on female protagonists

- Films exploring jealousy and revenge themes

- Griffith's later more ambitious feature films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in 16mm and 35mm copies through various film archives, including the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. While the original Biograph negative was lost in a vault fire in the 1920s, distribution prints have allowed for preservation. The film has been restored by several archives, with versions available on DVD through Kino Lorber as part of their D.W. Griffith collections. The quality varies between surviving copies, but the film remains largely complete and viewable.