The Gentlefolks of Skotinin

Plot

This satirical comedy follows the absurd and depraved Skotinin family, wealthy Russian nobles who embody the worst traits of the aristocracy. The family patriarch and his relatives engage in ridiculous schemes and immoral behavior while attempting to arrange a marriage for their ignorant and spoiled son. Through a series of farcical situations and over-the-top follies, the film exposes the moral bankruptcy and intellectual emptiness of the upper class. The narrative culminates in the exposure of their various schemes and the ultimate downfall of their pretentious social standing.

About the Production

The film was produced during the relatively liberal period of Soviet cinema in the 1920s, before Stalin's strict cultural policies took full effect. Director Grigoriy Roshal adapted Denis Fonvizin's classic 18th-century play 'The Minor' to create a satire that could also be interpreted as commentary on contemporary bourgeois elements in Soviet society. The production utilized the sophisticated techniques of Soviet montage theory while maintaining the theatrical origins of the source material.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1927, a crucial year in Soviet history marking the tenth anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. This period, known as the NEP (New Economic Policy) era, saw relative cultural liberalization and artistic experimentation in Soviet cinema. The film industry was still recovering from the civil war years but was producing some of its most innovative works. The adaptation of an 18th-century classical play about aristocratic corruption could be viewed as both a critique of pre-revolutionary Russia and a subtle commentary on emerging bourgeois tendencies in Soviet society. By 1927, Stalin was beginning to consolidate his power, and the cultural freedom that allowed such satirical works would soon be severely restricted with the implementation of Socialist Realism as the only approved artistic style.

Why This Film Matters

The Gentlefolks of Skotinin represents an important example of how Soviet filmmakers used classical Russian literature to create contemporary social commentary. The film is significant for its role in the tradition of Soviet satirical cinema, which used humor and exaggeration to critique social vices. Its adaptation of Fonvizin's classic play demonstrated how revolutionary cinema could engage with Russia's cultural heritage while serving ideological purposes. The film contributed to the development of Soviet comedy and satire, showing how historical material could be made relevant to modern audiences. It also exemplifies the sophisticated literary adaptations that characterized Soviet cinema before Stalinist cultural policies limited artistic expression.

Making Of

The production of 'The Gentlefolks of Skotinin' took place during a fascinating period of Soviet cinema when filmmakers still had considerable artistic freedom. Grigoriy Roshal, who had studied under Vsevolod Meyerhold, brought theatrical sensibilities to the screen adaptation. The cast included several prominent stage actors from Moscow's leading theaters, which was common for Soviet films of this era. The production team faced the technical limitations of late 1920s Soviet filmmaking, including limited film stock and basic equipment, yet managed to create elaborate sets and costumes that captured the 18th-century setting. The satirical nature of the material required careful handling to avoid censorship, even during this relatively liberal period.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'The Gentlefolks of Skotinin' employed the sophisticated techniques of Soviet montage theory while maintaining clear narrative storytelling. The visual style contrasted the opulent but decaying aristocratic interiors with the moral emptiness of the characters. Camera work emphasized the theatrical origins of the material through carefully composed shots that highlighted the actors' performances. The film used lighting to create dramatic effects that underscored the satirical nature of the story, with harsh lighting exposing the characters' flaws. Visual motifs related to excess and decay were woven throughout the cinematography to reinforce the film's themes.

Innovations

While not as technically innovative as some other Soviet films of 1927, 'The Gentlefolks of Skotinin' demonstrated solid craftsmanship in its adaptation of theatrical material to the cinematic medium. The film successfully translated the spatial relationships of stage drama into cinematic space through effective use of set design and camera placement. The production created convincing 18th-century period details within the constraints of Soviet film resources. The editing maintained the pacing necessary for comedy while incorporating some montage techniques characteristic of Soviet cinema of the era.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Gentlefolks of Skotinin' would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The typical score for Soviet comedies of this period would have included popular Russian folk tunes, classical selections, and original compositions that emphasized the comic and satirical elements. The musical accompaniment would have varied by theater, with larger cinemas employing full orchestras while smaller venues used piano or organ. The music would have been carefully synchronized with the on-screen action to enhance the comedic timing and dramatic moments.

Famous Quotes

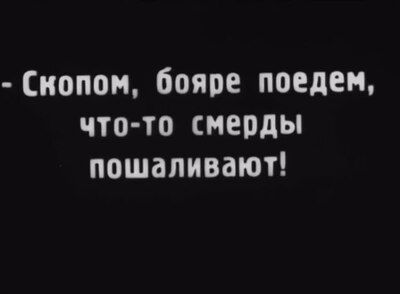

Quotes from this silent film are not typically preserved in written form, as the dialogue was conveyed through intertitles and pantomime

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene introducing the Skotinin family's absurd lifestyle

- The marriage negotiation sequences highlighting the mercenary nature of aristocratic alliances

- The exposure scene where the family's various schemes and hypocrisies are revealed

- The climatic downfall of the Skotinin social standing

Did You Know?

- The film is based on Denis Fonvizin's 1782 play 'The Minor' (Недоросль), one of the most famous Russian classical comedies

- Director Grigoriy Roshal was married to actress Vera Maretskaya, who appeared in several of his films

- The original play was considered revolutionary for its time as it criticized the Russian nobility and their poor educational practices

- 1927 was part of the golden age of Soviet silent cinema, the same year as classics like 'October' and 'The End of St. Petersburg'

- The film's title in Russian was 'Дворяне Скотинины' (Dvoryane Skotininy)

- The character name 'Skotinin' comes from the Russian word 'skot' meaning cattle, suggesting animalistic behavior

- This was one of Roshal's early directorial works before he became better known for his biographical films about cultural figures

- The film was part of a series of 1920s Soviet adaptations of classical Russian literature

- Varvara Massalitinova, who played a leading role, was a prominent actress at the Moscow Art Theatre

- The film was made just before the Great Turn in Soviet cultural policy that would restrict such satirical works

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its successful adaptation of Fonvizin's classic play and its effective use of cinematic techniques to enhance the satirical elements. Reviews highlighted the strong performances, particularly by Varvara Massalitinova, and the film's ability to make 18th-century social commentary relevant to 1920s audiences. However, as political winds shifted in the late 1920s and early 1930s, the film fell out of favor as Soviet cultural policy moved away from such satirical treatments of social issues. Modern film historians recognize the work as an important example of 1920s Soviet cinema's artistic achievements and its engagement with Russian literary tradition.

What Audiences Thought

The film was reportedly well-received by Soviet audiences in 1927, who appreciated both the humor and the literary pedigree of the source material. Contemporary viewers would have recognized the parallels between the 18th-century aristocratic decadence depicted and the social changes occurring in Soviet society. The film's theatrical origins and familiar classical story made it accessible to audiences who might have been less receptive to more experimental Soviet avant-garde works of the period. However, like many films from this era, its audience was limited by the still-developing distribution network of Soviet cinema and the relatively low literacy rates in rural areas.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Minor by Denis Fonvizin

- Soviet montage theory

- Theatrical tradition of Moscow Art Theatre

- 18th-century Russian satire

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet satirical works

- Other adaptations of classical Russian literature

- Social comedies of the late Soviet period

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'The Gentlefolks of Skotinin' is unclear, as many Soviet films from this period have been lost or exist only in incomplete copies. The film is believed to survive in at least partial form in Russian state archives, though it may not be widely available for viewing. Some sources suggest that elements of the film are preserved in the Gosfilmofond archive in Moscow, but complete restoration may be needed. The relative obscurity of the film compared to major Soviet works of 1927 suggests limited preservation efforts.