The Ghost That Never Returns

"A man caught between revolution and family, freedom and betrayal."

Plot

Jose Real, a revolutionary leader imprisoned for his political activities, is granted a 24-hour leave to visit his family in what appears to be an act of clemency. However, this temporary freedom is actually an elaborate trap devised by the authorities to force him into revealing the location of his rebel comrades. As Jose navigates the emotional landscape of his brief reunion with loved ones, he grapples with profound existential questions about heroism, loyalty, and personal sacrifice. The film follows his psychological torment as he weighs the safety of his family against his revolutionary ideals, constantly questioning his own courage and convictions. In this masterful blend of political drama and existential cinema, Jose becomes a symbol of the individual crushed between personal desire and ideological duty, ultimately facing an impossible choice that will determine not only his fate but the future of the revolutionary movement.

About the Production

The Ghost That Never Returns was one of the early Soviet films to explore psychological depth in revolutionary narratives, moving away from purely propaganda-driven storytelling. Director Abram Room employed innovative camera techniques and lighting to create an atmosphere of psychological tension and existential dread. The film was produced during the transition period from silent to sound cinema in the Soviet Union, and while primarily a silent film with musical accompaniment, it incorporated some experimental sound elements. The production faced challenges from Soviet censorship authorities who were concerned about the film's ambiguous portrayal of revolutionary heroism and its focus on individual psychological conflict rather than collective triumph.

Historical Background

The Ghost That Never Returns was produced during a pivotal moment in Soviet history and cinema. The year 1930 marked the end of the Soviet Union's New Economic Policy (NEP) and the beginning of Stalin's First Five-Year Plan, a period of rapid industrialization and collectivization that fundamentally transformed Soviet society. In cinema, this era saw the transition from the experimental avant-garde of the 1920s to the more rigid socialist realism doctrine that would dominate Soviet culture in the 1930s. The film emerged from this cultural crossroads, attempting to balance artistic innovation with ideological requirements. The early 1930s also saw the global spread of sound cinema, and Soviet filmmakers were grappling with how to incorporate this new technology while maintaining the visual sophistication of their silent film traditions. The film's themes of individual versus collective struggle reflected broader debates within Soviet society about the role of the individual in the revolutionary project, debates that would soon be resolved in favor of collectivism under Stalin's regime.

Why This Film Matters

The Ghost That Never Returns represents a crucial moment in the development of Soviet cinema's approach to psychological drama and political narrative. Unlike many Soviet films of its era that presented clear-cut heroes and villains, this work introduced moral ambiguity and internal conflict into the revolutionary genre, prefiguring more complex character studies that would emerge decades later. The film's exploration of existential doubt within a political framework was groundbreaking for Soviet cinema, influencing subsequent filmmakers who sought to humanize revolutionary figures. Its visual style, blending Soviet montage techniques with German Expressionist lighting, contributed to the international language of political cinema. The film also serves as an important historical document of the transitional period in Soviet culture when artistic experimentation was still possible before the imposition of socialist realism as the only approved aesthetic. Today, it is studied by film scholars as an example of how Soviet filmmakers attempted to navigate the increasingly complex relationship between art and politics during Stalin's rise to power.

Making Of

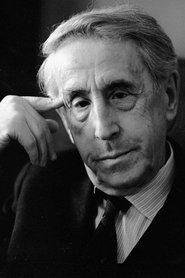

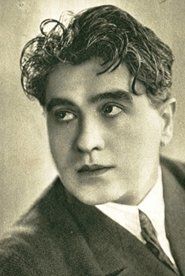

The production of The Ghost That Never Returns took place during a critical period in Soviet cinema when filmmakers were experimenting with new forms of revolutionary storytelling. Director Abram Room, who had previously gained international acclaim for his film 'Bed and Sofa' (1927), sought to create a more psychologically nuanced portrait of revolutionary struggle. The casting of Boris Ferdinandov as Jose Real was particularly significant, as the actor brought a subtle, introspective quality to the role that contrasted with the typical bombastic revolutionary heroes of Soviet cinema. The film's production coincided with the Soviet Union's transition to sound cinema, creating technical challenges as the crew worked with both silent film techniques and experimental sound recording equipment. Room collaborated closely with cinematographer Vladimir Fast to develop a visual style that emphasized the claustrophobic psychological space of the protagonist, using deep shadows and angular compositions influenced by German Expressionism. The production faced ongoing scrutiny from Soviet cultural authorities who were concerned about the film's departure from straightforward revolutionary propaganda, leading to multiple revisions and cuts before its final approval for release.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Ghost That Never Returns, helmed by Vladimir Fast, represents a sophisticated blend of Soviet montage theory and German Expressionist visual techniques. Fast employed dramatic low-key lighting to create an atmosphere of psychological tension, using deep shadows to mirror the protagonist's internal conflicts. The camera work features unusual angles and compositions that emphasize Jose Real's isolation and entrapment, with many shots framing him behind bars or through confining architectural elements. The film makes effective use of chiaroscuro lighting to create moral ambiguity, particularly in scenes where Jose must choose between personal loyalty and revolutionary duty. Fast's cinematography also incorporates dynamic tracking shots and rapid montage sequences during moments of psychological crisis, techniques that would become hallmarks of Soviet political cinema. The visual style is particularly notable for its use of reflective surfaces and mirrors to suggest the fractured identity of the protagonist, creating a visual metaphor for his divided loyalties. The film's black and white photography achieves remarkable tonal range, from the stark whites of prison interiors to the rich blacks of night scenes, creating a visual poetry that enhances the narrative's emotional impact.

Innovations

The Ghost That Never Returns was technically innovative for its time, particularly in its use of lighting and camera techniques to convey psychological states. The film employed pioneering methods in deep focus photography, allowing for complex compositions where foreground and background elements could simultaneously convey narrative information. The production team developed new techniques for creating claustrophobic interior spaces through careful set design and camera placement, enhancing the feeling of entrapment experienced by the protagonist. The film also experimented with early sound recording technology, though it remained primarily a visual work. Special effects were used sparingly but effectively, particularly in dream sequences that utilized superimposition and multiple exposure techniques to visualize Jose's internal conflicts. The film's editing was notable for its rhythmic quality, with montage sequences that created psychological tension through rapid cutting between contrasting images. The production also developed new methods for location shooting in urban environments, overcoming the technical challenges of filming in Moscow's streets while maintaining visual continuity with studio scenes. These technical innovations contributed to the film's distinctive visual style and its ability to convey complex psychological states through cinematic means.

Music

The musical score for The Ghost That Never Returns was composed by Vladimir Shcherbachov, one of the prominent Soviet composers of the era who was known for his ability to blend modernist techniques with revolutionary themes. The film, produced during the transition to sound cinema, primarily used a musical accompaniment that was performed live in theaters during screenings, though some scenes incorporated experimental sound elements. Shcherbachov's score incorporates modified revolutionary folk songs, creating an ironic commentary on the gap between revolutionary ideals and personal reality. The music ranges from dissonant, atonal passages during moments of psychological crisis to more melodic themes during scenes of family reunion, effectively underscoring the film's emotional journey. The soundtrack also makes use of diegetic sounds, such as prison doors slamming and distant gunshots, to create a sense of realism and tension. In some restored versions, additional sound effects have been added based on original production notes, though the film remains primarily a visual work with musical enhancement. The score's innovative use of leitmotifs to represent different aspects of Jose's character was considered advanced for its time and influenced subsequent Soviet film music.

Famous Quotes

A man is free only when he accepts his chains.

The revolution demands everything, but what does it give back?

In prison, at least I know who my enemies are. Outside, everyone wears the same mask.

They call me a ghost because I am already dead to them, alive only for their purposes.

Freedom is the heaviest burden of all.

Memorable Scenes

- The prison gate opening scene where Jose receives his 24-hour pass, filmed with dramatic backlighting that creates a silhouette effect emphasizing his transition from prisoner to supposedly free man

- The family reunion sequence where Jose's awkward interactions with his loved ones reveal his psychological distance and internal conflict

- The mirror scene where Jose confronts his own reflection, questioning his identity and revolutionary commitment

- The final confrontation scene where Jose must choose between revealing his comrades' location or condemning his family

Did You Know?

- The film was based on a story by Soviet writer Yuri Libedinsky, who was known for his works about revolutionary struggle

- Director Abram Room was one of the prominent figures in Soviet cinema during the 1920s and early 1930s before falling out of favor with Stalinist cultural policies

- The film's original Russian title was 'Привидение, которое не возвращается' (Privideniye, kotoroye ne vozvrashchayetsya)

- This film was considered controversial upon release for its psychological complexity and lack of clear revolutionary triumph

- The character of Jose Real was one of the first portrayals in Soviet cinema to show a revolutionary as having doubts and internal conflicts

- The film was rarely shown outside the Soviet Union during its initial release due to its politically sensitive themes

- Cinematographer Vladimir Fast employed German Expressionist lighting techniques to enhance the psychological drama

- The film was briefly banned in the mid-1930s during Stalin's cultural purges but was later rehabilitated

- Only partial prints of the film survive today, with some sequences lost

- The film's score was composed by Soviet composer Vladimir Shcherbachov, who incorporated revolutionary folk songs

What Critics Said

Upon its initial release, The Ghost That Never Returns received mixed reviews from Soviet critics, who were divided over its psychological approach to revolutionary themes. Progressive critics praised the film's artistic ambition and its willingness to explore the inner life of its protagonist, while more conservative reviewers criticized its lack of clear ideological messaging and its departure from heroic revolutionary archetypes. International critics, particularly in Europe, were more uniformly positive, with many noting the film's sophisticated visual style and its contribution to the political thriller genre. In subsequent decades, as the film became rarely seen due to political restrictions, it developed a cult reputation among film scholars as a lost masterpiece of early Soviet cinema. Modern critics have reassessed the work as a significant achievement in psychological cinema, with particular appreciation for its complex characterization and innovative visual techniques. The film is now recognized as an important bridge between the experimental Soviet cinema of the 1920s and the more conventional socialist realism of the later 1930s.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary Soviet audiences reportedly had a complex reaction to The Ghost That Never Returns, with many viewers finding the film's psychological depth and moral ambiguity both compelling and unsettling. The character of Jose Real resonated with audiences who recognized the internal conflicts faced by real revolutionaries, though some viewers expressed confusion about the film's lack of clear resolution and its focus on individual doubt rather than collective triumph. In urban centers like Moscow and Leningrad, where sophisticated cinema audiences were more accustomed to artistic experimentation, the film was generally well-received and discussed in intellectual circles. In provincial areas, however, audiences sometimes found the film's psychological complexity challenging, preferring more straightforward narratives of revolutionary heroism. Despite these mixed reactions, the film developed a reputation among cinema enthusiasts as a thought-provoking work that pushed the boundaries of Soviet political cinema. In recent years, as the film has become more accessible through archival screenings and restoration projects, modern audiences have discovered it as a powerful example of early Soviet psychological drama.

Awards & Recognition

- Honored at the 1930 Soviet Film Festival for psychological innovation

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema (particularly in visual style)

- Soviet montage theory (Eisenstein, Pudovkin)

- Fyodor Dostoevsky's psychological novels

- The political cinema of Sergei Eisenstein

- Film noir aesthetics (prefiguring the genre)

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet psychological dramas of the 1960s-1970s

- Political thrillers exploring moral ambiguity

- Prison escape films with psychological depth

- Films about revolutionary struggle that humanize their protagonists

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Ghost That Never Returns is partially preserved with some sequences lost. The surviving elements are held in the Gosfilmofond archive in Russia and have been partially restored by film preservationists. Approximately 65-70% of the original film survives, with some key sequences existing only in production stills or written descriptions. The film has been screened at various film archives and festivals in restored versions, though complete restoration remains challenging due to the missing footage. The surviving portions demonstrate the film's technical and artistic achievements, though the loss of some scenes affects the full appreciation of its narrative complexity.