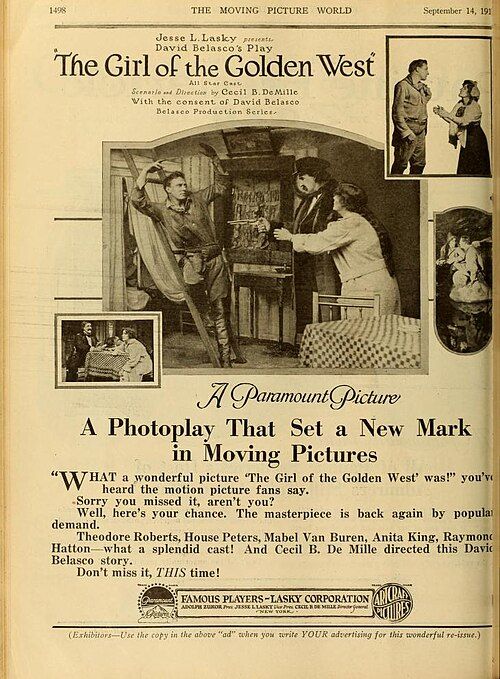

The Girl of the Golden West

"A Drama of the California Gold Rush Days"

Plot

Set in a California mining camp during the Gold Rush era, the story follows Mary, the owner of the Polka Saloon, who is beloved by the local miners but secretly loves Ramerrez, a notorious bandit known as the 'Ramirez.' Sheriff Jack Rance, who desperately loves Mary, discovers Ramerrez's true identity when he captures him and brings him to the saloon. In a dramatic climax, Rance proposes a high-stakes poker game: if Mary wins, Ramerrez goes free; if she loses, she must marry Rance. Mary cleverly cheats to save her lover, and when Rance discovers her deception, he magnanimously allows them to escape together, riding off into the sunset as the miners watch in astonishment.

About the Production

This was Cecil B. DeMille's first Western film and one of the earliest feature-length Westerns. The film was based on David Belasco's 1905 play 'The Girl of the Golden West,' which had also inspired Puccini's opera 'La fanciulla del West.' DeMille insisted on authentic costumes and props, hiring actual mining equipment from California's Gold Rush regions. The production faced challenges with the elaborate saloon set, which had to be built to accommodate both the dramatic scenes and the large cast of extras playing miners.

Historical Background

The Girl of the Golden West was produced during a pivotal moment in American cinema history, as the industry was transitioning from short films to feature-length productions. 1915 marked the rise of Hollywood as the center of American filmmaking, with companies like the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company (which would later become Paramount Pictures) establishing themselves as major players. The film reflected America's continuing fascination with the mythologized American West, even as the actual frontier had largely disappeared decades earlier. This period also saw the beginning of film censorship efforts, particularly regarding content involving gambling and romantic relationships, making DeMille's inclusion of a poker game scene somewhat controversial. The film's production coincided with World War I in Europe, which helped establish American cinema's dominance in the global market as European film production was disrupted.

Why This Film Matters

This film holds an important place in cinema history as one of the earliest feature-length Westerns, helping to establish many conventions that would define the genre for decades. It demonstrated that Western themes could sustain a feature-length narrative rather than just short films. The film's portrayal of a strong, independent female protagonist in Mary was somewhat progressive for its time, challenging traditional gender roles in Western storytelling. Its success helped cement Cecil B. DeMille's reputation as a director capable of handling large-scale productions and complex narratives. The film also represents an early example of adapting stage works to cinema, a practice that would become increasingly common as the film industry matured. Its blend of romance, action, and moral complexity influenced countless subsequent Western films.

Making Of

Cecil B. DeMille approached this project with meticulous attention to historical accuracy, researching California Gold Rush history extensively. He hired actual miners as consultants and technical advisors. The saloon set was one of the most elaborate built in Hollywood up to that time, featuring a working bar, gambling tables, and period-accurate decorations. DeMille was known for his perfectionism and reportedly reshot the climactic poker scene multiple times until he was satisfied with the dramatic tension. The film was shot during an unusually cold California winter, which created challenges for the cast and crew but added authenticity to the outdoor scenes. House Peters, who played Ramerrez, performed many of his own stunts, including horseback riding sequences that were considered dangerous for the time.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by Alvin Wyckoff, was considered advanced for its time. Wyckoff employed innovative lighting techniques to create dramatic shadows in the saloon scenes, enhancing the film's emotional intensity. The use of natural light for the outdoor sequences was particularly praised, with the California mountain locations providing striking visual backdrops. The film featured several tracking shots that were technically challenging for 1915, including a sequence following a horseback chase through mountainous terrain. The poker game scene was shot with careful attention to facial expressions and hand movements, using close-ups that were still relatively rare in feature films of this era.

Innovations

The film featured several technical innovations for its time, including the use of artificial snow effects created through a combination of salt and cotton, which was groundbreaking in 1915. The elaborate saloon set incorporated working mechanical elements, including a functioning roulette wheel and card dealing devices. The film employed multiple camera angles for the poker game scene, a technique that was still being developed during this period. The production also pioneered the use of location shooting for Westerns, moving away from the studio-bound productions that were common at the time. The film's special effects, including simulated gunfights and horseback stunts, were considered particularly realistic for the era.

Music

As a silent film, The Girl of the Golden West would have been accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. The original score was composed by William Furst, who was the house composer for the Lasky Company. The music incorporated elements of American folk tunes and popular songs of the Gold Rush era, including 'Oh! Susanna' and 'Clementine.' Larger theaters would have used full orchestras, while smaller venues relied on piano or organ accompaniment. The score emphasized the romantic elements with lush strings and the action sequences with more percussive instrumentation. Some theaters reportedly used portions of Puccini's opera score for special presentations, creating an interesting hybrid of classical and popular music.

Famous Quotes

"A man's life is worth more than gold, but a woman's love is worth more than either." - Sheriff Rance

"In this camp, we make our own justice." - Mary

"Love makes fools of us all, but only the brave admit it." - Ramerrez

"The cards don't lie, but sometimes the players do." - During the poker game

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic poker game where Mary risks everything to save Ramerrez, with tension building as each card is dealt and the fate of all three characters hangs in the balance

- The opening sequence showing the bustling mining camp and introducing the colorful characters of the Polka Saloon

- Ramerrez's dramatic entrance into the saloon, disguised and unrecognized by all except Mary

- The final escape scene where Mary and Ramerrez ride off together as the miners watch in stunned silence

- The confrontation between Sheriff Rance and Ramerrez where the bandit's true identity is revealed

Did You Know?

- This was the first film adaptation of David Belasco's play, predating the famous opera by Puccini which had premiered in 1910

- Cecil B. DeMille considered this film one of his most important early works, as it established his reputation for handling large-scale productions

- The film featured one of the first uses of artificial snow in cinema, created using cotton and salt

- Mabel Van Buren was a stage actress before this film and this was only her second motion picture appearance

- The poker game scene was considered particularly daring for its time, showing a woman gambling in a mixed-gender setting

- DeMille insisted on filming on location in the California mountains for authenticity, unusual for 1915 productions

- The film's success helped establish the Western as a viable genre for feature-length films

- Theodore Roberts, who played Sheriff Rance, was one of DeMille's favorite character actors and appeared in over 20 of his films

- The original play had been a Broadway hit starring Blanche Walsh, who was considered for the film role but declined

- The film's title was sometimes shortened to 'The Golden West' in some advertisements to save space

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's ambitious scope and DeMille's direction. The New York Dramatic Mirror called it 'a triumph of motion picture art' and particularly noted the authenticity of the Gold Rush setting. Variety praised the performances, especially Mabel Van Buren's portrayal of Mary, calling it 'a revelation of screen acting.' Modern critics and film historians recognize the film as an important early Western that helped establish many genre conventions, though some note that its pacing and acting style reflect the limitations of the era. The film is often cited in studies of DeMille's early career and the development of the Western genre.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a popular success with audiences of its time, particularly in the American West where its authentic settings resonated with viewers. Contemporary accounts report that audiences were especially moved by the dramatic poker game scene and Mary's clever solution to her dilemma. The film's themes of love, honor, and sacrifice appealed to the moral sensibilities of 1915 audiences. Its success led to increased demand for Western features and helped establish the commercial viability of the genre. Audience response was strong enough that the film remained in circulation for several years, unusual for a feature of this period.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- David Belasco's 1905 stage play 'The Girl of the Golden West'

- Puccini's opera 'La fanciulla del West' (1910)

- Contemporary Western literature and dime novels

- American frontier mythology

- Earlier short Western films by D.W. Griffith and others

This Film Influenced

- The Girl of the Golden West (1930) - sound remake

- The Girl of the Golden West (1938) - Jeanette MacDonald/Nelson Eddy version

- Numerous subsequent Westerns featuring strong female protagonists

- Later DeMille Westerns including 'The Plainsman' (1936)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is considered lost, like approximately 90% of American films from this period. No complete prints are known to exist in any film archives worldwide. However, some fragments and still photographs from the production survive, providing visual documentation of the film's style and content. The Library of Congress maintains a collection of production stills and promotional materials. Film historians continue to search for any surviving copies, particularly in European archives where some American films were preserved. The loss of this film is particularly significant due to its importance in DeMille's early career and the development of the Western genre.