The Golden Key

"The magical tale of a wooden boy's quest for freedom and friendship"

Plot

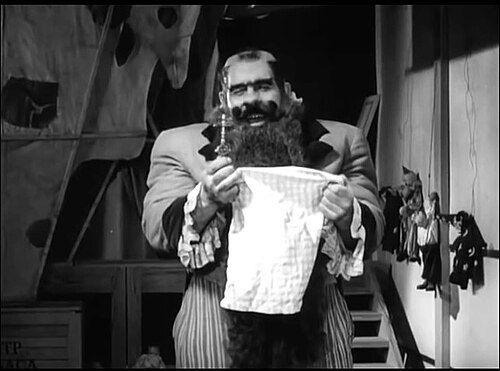

The Golden Key follows the adventures of Buratino (the Russian Pinocchio), a wooden puppet created by the kind but poor Papa Carlo. Buratino discovers that a mysterious golden key, given to him by the wise Tortilla the turtle, can unlock a magical door leading to a world of wonders and puppet freedom. Along his journey, he befriends other puppets including the poetic Pierrot, the beautiful Malvina, and her loyal poodle Artemon, while evading the evil puppet master Karabas-Barabas and his scheming accomplices Alice the Fox and Basilio the Cat. The story culminates in a climactic confrontation where Buratino must use the golden key to liberate all puppets from their puppet master's tyranny and find his own path to becoming a real boy.

About the Production

The Golden Key was a groundbreaking technical achievement, combining live-action actors with stop-motion animated puppets in a way never before seen in Soviet cinema. Director Aleksandr Ptushko, known as the 'Soviet Disney,' pioneered techniques that involved intricate puppet construction and frame-by-frame animation. The production took over two years to complete, with puppet makers working tirelessly to create the detailed characters. The film's production was complicated by the political climate of 1930s Soviet Union, requiring careful navigation of Stalinist censorship while maintaining the fairy tale's magical elements.

Historical Background

The Golden Key was produced during a critical period in Soviet history, just before the outbreak of World War II. The late 1930s saw Stalin's Great Purge reaching its peak, yet simultaneously, there was a push for cultural works that could inspire and educate Soviet youth. The film emerged from Soyuzdetfilm, the world's first film studio dedicated exclusively to children's cinema, established in 1936. This period also saw the Soviet Union emphasizing technical innovation in cinema to compete with Western films, particularly Disney's animations. The choice to adapt Pinocchio through a distinctly Russian lens reflected the Soviet policy of taking foreign cultural elements and transforming them to align with socialist values. The film's themes of liberation from tyranny and the triumph of the common puppet over the oppressive puppet master carried subtle political undertones that resonated with contemporary Soviet audiences.

Why This Film Matters

The Golden Key holds a unique place in cinema history as one of the earliest feature-length films to successfully blend live-action with stop-motion animation. It established Aleksandr Ptushko as a pioneering figure in special effects and animation, influencing generations of filmmakers both within and beyond the Soviet Union. The film's Buratino became an iconic character in Russian culture, arguably more beloved than the original Pinocchio in Soviet and post-Soviet territories. The movie demonstrated that complex fantasy stories could be told through innovative technical means, paving the way for later masterpieces like Ptushko's 'Sadko' (1952) and 'Ilya Muromets' (1956). The film's artistic style, combining Russian folk art motifs with modern animation techniques, created a visual language that would influence Soviet animation for decades. Its success proved that children's films could be both artistically ambitious and commercially viable in the Soviet system.

Making Of

The making of The Golden Key was a monumental technical undertaking for Soviet cinema in 1939. Director Aleksandr Ptushko assembled a team of over 100 craftsmen, puppet makers, and animators to bring the story to life. The puppets were constructed using a revolutionary technique involving metal armatures covered with special plastic materials that allowed for both durability and flexibility. Each main puppet required approximately three months to build, with the Buratino puppet alone featuring over 25 separate control points for animation. The live-action sequences were filmed on specially constructed sets that could seamlessly integrate with the stop-motion footage. The production team developed new camera mounting systems and lighting techniques to ensure the live actors and animated puppets appeared to occupy the same space convincingly. The film's score was composed by Sergei Prokofiev's student, Lev Shvarts, who created memorable themes that became classics in Soviet children's music.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Golden Key was groundbreaking for its time, employing innovative techniques to seamlessly blend live-action and stop-motion elements. Cinematographer Fyodor Provorov developed new lighting methods that could accommodate both actors and puppets in the same frame, creating consistent shadows and highlights across different media. The film used forced perspective and carefully constructed miniature sets to maintain scale relationships between human actors and puppet characters. The camera movements were meticulously planned to ensure smooth transitions between live and animated sequences, with some shots requiring up to three days to complete. The visual style incorporated elements of Russian folk art, particularly in the set designs and color palette, creating a distinctly Soviet fantasy aesthetic. The film also featured innovative use of matte paintings and multiple exposure techniques to create magical effects that would influence later Soviet fantasy films.

Innovations

The Golden Key represented a quantum leap in film technology for the Soviet cinema industry. The film pioneered the use of advanced stop-motion animation techniques, including the development of ball-and-socket armatures that allowed for more fluid and realistic puppet movements. The production team created custom-built animation rigs and camera control systems that could execute complex camera movements while maintaining precise frame-by-frame animation control. The film featured one of the earliest uses of traveling matte techniques in Soviet cinema, allowing live actors to interact directly with animated characters. The special effects department developed new methods for creating magical elements, including innovative uses of smoke, mirrors, and multiple exposures. The sound recording techniques used for the film were also advanced for their time, featuring early attempts at creating spatial audio effects to enhance the fantasy atmosphere. These technical achievements established new standards for special effects in Soviet cinema and influenced numerous subsequent productions.

Music

The musical score for The Golden Key was composed by Lev Shvarts, a student of the famous Sergei Prokofiev, who created a memorable and whimsical soundtrack that perfectly complemented the film's fantastical elements. The music incorporated Russian folk melodies with classical orchestral arrangements, creating a unique sound that became instantly recognizable to Soviet audiences. Several songs from the film became popular hits in their own right, particularly Buratino's theme song and the menacing motif associated with Karabas-Barabas. The soundtrack was recorded using the then-new optical sound-on-film technology, allowing for higher quality audio reproduction than previous Soviet films. The musical numbers were carefully synchronized with the puppet animations, requiring precise timing during both the recording and animation processes. The score's success led to its release as a separate album, one of the first film soundtracks to receive such treatment in the Soviet Union.

Famous Quotes

Buratino: 'I am not a wooden boy! I have a heart that beats with courage!'

Karabas-Barabas: 'Puppets should know their place! They belong on strings, not running free!'

Tortilla: 'The golden key opens not just a door, but the path to your true self.'

Malvina: 'Kindness is the greatest magic of all.'

Papa Carlo: 'Even a wooden boy can learn to love and be loved.'

Pierrot: 'In this world of strings and stages, we must find our own truth.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Buratino comes to life and escapes from Papa Carlo's workshop, showcasing the innovative blend of live-action and stop-motion animation

- The underwater scene where Buratino meets Tortilla the turtle, featuring pioneering underwater effects and beautiful lighting

- The final confrontation between Buratino and Karabas-Barabas, where the golden key reveals its true power and all puppets are liberated

- The puppet theater sequence where the characters perform their own show, featuring intricate choreography between live actors and animated puppets

- The magical door opening scene, where the golden key transforms the ordinary into the extraordinary with stunning visual effects

Did You Know?

- This was the first Soviet feature film to combine live-action with stop-motion animation

- Director Aleksandr Ptushko was often called the 'Soviet Walt Disney' for his innovative animation techniques

- The film is based on Alexei Tolstoy's 1936 novel 'The Golden Key, or the Adventures of Buratino,' which was a Russian adaptation of Carlo Collodi's Pinocchio

- The puppets were created using a complex system of joints and mechanisms, with some having up to 30 movable parts

- Sergei Martinson, who played Karabas-Barabas, was one of Soviet cinema's most beloved character actors

- The film's stop-motion sequences were filmed at 12 frames per second, requiring meticulous attention to detail

- The Tortilla the turtle character was one of the most technically challenging puppets to animate due to its complex shell movements

- The original film negative was partially damaged during World War II but was later restored

- The film was released just weeks before the Soviet invasion of Poland, making it one of the last major cultural releases before the war intensified

- Many of the puppet designs were inspired by traditional Russian folk art and lacquer boxes

What Critics Said

Upon its release in 1939, The Golden Key received widespread critical acclaim in the Soviet press, with Pravda praising it as 'a triumph of Soviet cinematic art.' Critics particularly lauded the innovative technical achievements and the seamless integration of live-action and animation. Western critics who later saw the film during limited international screenings in the 1950s and 1960s expressed astonishment at its sophistication, with some comparing Ptushko's work favorably to contemporary Disney productions. Modern film historians consider The Golden Key a milestone in the history of special effects and animation, often citing it as an overlooked masterpiece that predates many similar techniques developed in the West. The film's restoration and re-release in the 2000s led to renewed critical appreciation, with contemporary reviewers noting its enduring charm and technical brilliance.

What Audiences Thought

The Golden Key was enormously popular with Soviet audiences upon its release, particularly with children who were captivated by the magical story and innovative visuals. The film ran in Soviet cinemas for several years, an unusual longevity for the time, and became a staple of children's matinee screenings throughout the 1940s and 1950s. Many Soviet children grew up with Buratino as their version of Pinocchio, and the character entered the popular imagination through numerous references in jokes, literature, and everyday speech. The film's popularity endured through the Soviet era and continues in post-Soviet Russia, where it remains a beloved classic. Audience members often cite the film's imaginative visuals, memorable characters, and the performance of Sergei Martinson as Karabas-Barabas as particular highlights. The movie's annual television broadcasts during holiday seasons became a tradition for many Soviet families.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, Second Class (1941) - awarded to Aleksandr Ptushko for outstanding achievement in filmmaking

- All-Union Film Festival Prize for Best Children's Film (1958, retrospective award)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Carlo Collodi's 'The Adventures of Pinocchio' (1883)

- Alexei Tolstoy's 'The Golden Key' (1936)

- Early Disney animations, particularly 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs' (1937)

- Russian folk tales and puppet theater traditions

- German Expressionist cinema for visual style

- Soviet socialist realist art principles

This Film Influenced

- The New Gulliver (1935) - Ptushko's earlier animation work that influenced this film

- Sadko (1952) - Ptushko's later fantasy film

- Ilya Muromets (1956) - Ptushko's epic fantasy

- The Snow Queen (1957) - Soviet animated feature

- Willow (1988) - Western fantasy film with similar themes

- The Adventures of Pinocchio (1996) - Live-action adaptation

- Corpse Bride (2005) - Stop-motion technique influence

- Coraline (2009) - Modern stop-motion fantasy

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Golden Key has been partially preserved and restored. The original film negative suffered damage during World War II when storage facilities were bombed, but complete copies survived in the Soviet film archive. A major restoration project was undertaken in the early 2000s by the Gosfilmofond of Russia, which digitally remastered the film and restored damaged frames. The restored version was released on DVD in 2005 and later on Blu-ray in 2015. While some original color elements have been lost, the film survives in watchable condition and remains accessible to audiences through various streaming platforms and special screenings at film archives and museums.