The Great Gabbo

"He Talked Through His Wooden Friend!"

Plot

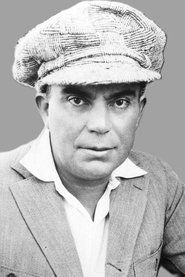

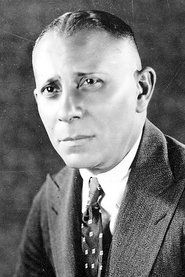

The Great Gabbo tells the story of a brilliant but arrogant ventriloquist named Gabbo (Erich von Stroheim) whose wooden dummy Otto becomes his only means of emotional expression. Gabbo's relationship with his assistant Mary (Betty Compson) deteriorates as he becomes increasingly dependent on Otto, using the dummy to say things he cannot express himself. When Mary leaves him to join a rival act with another performer (Donald Douglas), Gabbo's mental state begins to unravel completely. The film culminates in a dramatic breakdown where Gabbo can no longer distinguish between himself and his dummy, leading to a tragic finale that explores the dark side of fame and the psychological cost of artistic obsession.

About the Production

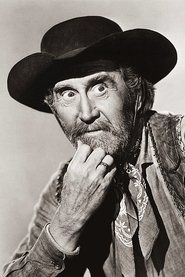

The film was one of the earliest all-talking musicals, produced during the difficult transition from silent to sound cinema. The production faced numerous technical challenges with early sound recording equipment, which required actors to remain largely stationary during dialogue scenes. Von Stroheim, who had been a major director in the silent era, was reportedly difficult during filming, clashing with director James Cruze over creative control. The film's elaborate musical numbers were staged with the limitations of early sound technology in mind, resulting in somewhat static camera work during these sequences.

Historical Background

The Great Gabbo was produced in 1929, a pivotal year in cinema history as Hollywood was fully transitioning from silent films to 'talkies.' This period, known as the sound revolution, was marked by technical experimentation, budget overruns, and career upheavals for many silent film stars. The film was released just months before the stock market crash of October 1929, which would trigger the Great Depression and dramatically change American entertainment consumption patterns. The late 1920s also saw the rise of psychological themes in cinema, influenced by the growing public interest in Freudian psychology and modernist ideas about the human mind. The ventriloquist dummy as a symbol of split personality and repressed desires tapped into contemporary anxieties about identity and mental health. Additionally, 1929 was the year that the Academy Awards were first presented (for films of 1927-28), and the industry was establishing new standards for what constituted a quality sound film. The film's blend of musical entertainment with dark psychological elements reflected the uncertainty of the era, as filmmakers experimented with the possibilities of sound while audiences grappled with rapid social and technological changes.

Why This Film Matters

The Great Gabbo holds an important place in cinema history as one of the first sound films to explore psychological horror themes, particularly the ventriloquist/dummy relationship that would become a horror subgenre. The film predates more famous examples like 'The Devil Doll' (1936) and 'Magic' (1978), establishing many of the tropes that would define ventriloquist horror cinema. Its exploration of the relationship between artist and creation, and the blurring of identity between creator and their work, resonated with modernist artistic concerns of the late 1920s. The film also represents a significant moment in Erich von Stroheim's career, marking his transition from respected silent film director to character actor in sound films. As an early musical, it demonstrates how filmmakers initially struggled to integrate musical numbers into dramatic narratives, often resulting in awkward tonal shifts. The film's commercial failure also illustrates the risks studios took during the sound transition, as they invested heavily in new technology without fully understanding audience preferences. Despite its flaws, 'The Great Gabbo' influenced later psychological horror films and remains a fascinating artifact of early sound cinema experimentation.

Making Of

The production of 'The Great Gabbo' was fraught with difficulties from the beginning. Erich von Stroheim, who had directed acclaimed silent films like 'Greed' and 'The Wedding March,' was initially set to direct but was replaced after conflicts with the studio over his meticulous and expensive approach to filmmaking. James Cruze took over direction, but tensions remained high on set. The transition to sound technology created numerous technical challenges, with the bulky recording equipment limiting camera movement and forcing actors to deliver their performances in a more theatrical style. Von Stroheim, known for his perfectionism, struggled with the constraints of early sound recording and often demanded multiple takes that frustrated the production schedule. The musical sequences were particularly difficult to stage, requiring the orchestra to be recorded separately and synchronized with the on-screen action. Betty Compson later recalled that von Stroheim remained in character as Gabbo even between takes, creating an unsettling atmosphere on set. The film's dark themes and von Stroheim's intense performance made some cast and crew uncomfortable, with several reporting that the dummy Otto seemed to have a disturbing presence on set.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'The Great Gabbo' was handled by Ira H. Morgan, who faced the significant challenge of working with early sound recording equipment. The bulky and insensitive sound recording technology of 1929 severely limited camera movement, resulting in many static shots that give the film a theatrical quality. Morgan employed dramatic lighting to enhance the psychological elements of the story, using stark shadows and high-contrast lighting particularly in scenes featuring Gabbo alone with his dummy. The film uses German Expressionist-inspired lighting techniques to create an unsettling atmosphere, especially in the sequences where Gabbo's mental state deteriorates. During the musical numbers, Morgan attempted more dynamic compositions within the technical constraints, using elaborate sets and careful blocking to create visual interest. The close-ups of von Stroheim as Gabbo are particularly effective, capturing the actor's intense facial expressions and the psychological tension of his performance. The cinematography also makes effective use of the dummy Otto as a visual motif, often framing shots to emphasize the eerie relationship between man and puppet. While limited by early sound technology, the film's visual style successfully contributes to its unsettling atmosphere and psychological impact.

Innovations

As an early sound film, 'The Great Gabbo' represents several technical achievements and innovations for its time, despite its overall commercial failure. The film was one of the first to attempt a serious psychological drama using sound technology, exploring how audio elements could enhance psychological horror. The ventriloquism sequences presented unique technical challenges, requiring precise synchronization between von Stroheim's lip movements and the dummy's 'voice.' The film's sound engineers developed techniques for recording dialogue that would appear to come from an inanimate object, which was innovative for 1929. The musical sequences demonstrated early attempts at recording and synchronizing orchestral music with on-screen performance, though the results were sometimes uneven. The production also experimented with sound perspective, attempting to create different audio qualities for the human and dummy voices. While the film's technical aspects were sometimes crude by later standards, they pushed the boundaries of what was possible with early sound recording equipment. The film's use of sound to create psychological tension rather than just for dialogue or music was particularly innovative, influencing later horror and thriller films that would use audio elements to create atmosphere and suspense.

Music

The soundtrack for 'The Great Gabbo' was composed by Cecil Copping and included several original songs that were typical of early musical films. The most notable number was 'The Web of Love,' which became a minor hit despite the film's overall failure. The score blended popular song styles of the late 1920s with more dramatic musical underscoring for the psychological scenes. The film featured a mix of diegetic music performed within the story and non-diegetic background score, demonstrating early sound cinema's experimentation with different approaches to film music. The musical sequences were staged as vaudeville-style performances within the narrative, reflecting the film's origins in popular entertainment forms. The sound design was particularly innovative for its use of the dummy's voice as a psychological element, with von Stroheim providing both Gabbo's and Otto's dialogue. The recording quality reflects the limitations of early sound technology, with some noticeable audio inconsistencies and a lack of ambient sound typical of the period. Despite these technical limitations, the film's use of sound was ambitious for its time, attempting to create a complex audio landscape that supported the psychological themes of the story.

Famous Quotes

Gabbo: 'Otto is my mouthpiece. He says what I cannot say.'

Mary: 'You're not Gabbo anymore. You're just Otto's shadow.'

Otto (through Gabbo): 'We are one, master. One mind, one voice.'

Gabbo: 'Without Otto, I am nothing. With Otto, I am everything.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening theater performance where Gabbo and Otto first demonstrate their uncanny connection, with the dummy seemingly moving and speaking independently

- The backstage confrontation between Gabbo and Mary where Gabbo lets Otto speak his true feelings, revealing the depth of his psychological dependence

- The final breakdown scene where Gabbo, alone in his dressing room, has a complete psychotic episode and can no longer distinguish himself from Otto

- The musical number 'The Web of Love' performed by Mary and her new partner, which contrasts with Gabbo's dark descent into madness

Did You Know?

- Erich von Stroheim was originally hired as both actor and director, but was replaced as director by James Cruze after creative disputes and budget concerns

- The film was one of the earliest examples of a psychological horror film in the sound era, predating more famous ventriloquist horror films by decades

- The dummy Otto was created by prop maker Theodore Mead and was reportedly so realistic that it unnerved many cast and crew members

- Betty Compson, who played Mary, had been a major silent film star and was making her transition to sound with this film

- The film featured the popular song 'The Web of Love' which became a minor hit despite the film's commercial failure

- Von Stroheim insisted on performing all of Otto's dialogue himself without any post-production dubbing, making the ventriloquism scenes particularly challenging

- The film's original running time was approximately 100 minutes, but it was cut to 89 minutes after poor preview screenings

- This was one of the first films to explore the psychological horror of ventriloquism, a theme that would become a horror subgenre

- The film's failure contributed to von Stroheim's declining career as a leading man in Hollywood

- Despite being a musical, the film's dark psychological elements made it difficult to market to audiences expecting light entertainment

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'The Great Gabbo' was largely negative, with most reviewers finding the film tonally inconsistent and technically awkward. The New York Times criticized the film's 'uneven mixture of melodrama and musical numbers,' while Variety noted that von Stroheim's performance was 'too intense for the material.' Many reviewers felt that the film couldn't decide whether it wanted to be a serious psychological drama or a light musical entertainment. The technical limitations of early sound recording were also noted, with critics commenting on the static camera work and theatrical acting style. However, some critics praised von Stroheim's intense performance and the film's ambitious attempt to blend different genres. Modern reappraisals have been more sympathetic, with film historians recognizing the movie as an important early example of psychological horror and a fascinating document of the transition to sound. Critics now appreciate the film's dark themes and von Stroheim's committed performance, even while acknowledging its technical and narrative flaws. The film is often cited in studies of early sound cinema and horror film history as a pioneering work that explored themes that would become more common in later decades.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception to 'The Great Gabbo' was poor, contributing to its commercial failure at the box office. Moviegoers in 1929 were still adjusting to sound films, and the dark psychological themes combined with musical numbers proved confusing and off-putting to many viewers. The film's unsettling exploration of mental illness and the disturbing relationship between Gabbo and his dummy Otto was too intense for audiences seeking the light entertainment typical of early musicals. Many theatergoers found von Stroheim's performance too menacing for what they expected to be a musical drama. The film's poor word-of-mouth reception led to short theatrical runs in most markets, and it was quickly pulled from circulation. Contemporary audience surveys and exhibitor reports indicated that the film was particularly unpopular with female viewers, who found the psychological elements too disturbing. However, a small segment of audiences appreciated von Stroheim's intense performance and the film's departure from typical musical fare. Over the decades, the film has developed a cult following among classic film enthusiasts and horror fans who appreciate its historical significance and von Stroheim's committed performance.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema

- Freudian psychology

- Vaudeville and stage performance traditions

- Earlier silent film psychological dramas

This Film Influenced

- The Devil Doll (1936)

- Dead of Night (1945) - specifically the ventriloquist segment

- Magic (1978)

- Child's Play (1988) series

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Library of Congress and has been restored by several archives. While not considered lost, some elements show deterioration due to the age of the original nitrate materials. The film exists in its complete form and has been released on DVD and Blu-ray by specialty labels. The soundtrack elements have been digitally remastered to improve audio quality, though some artifacts of early sound recording remain.