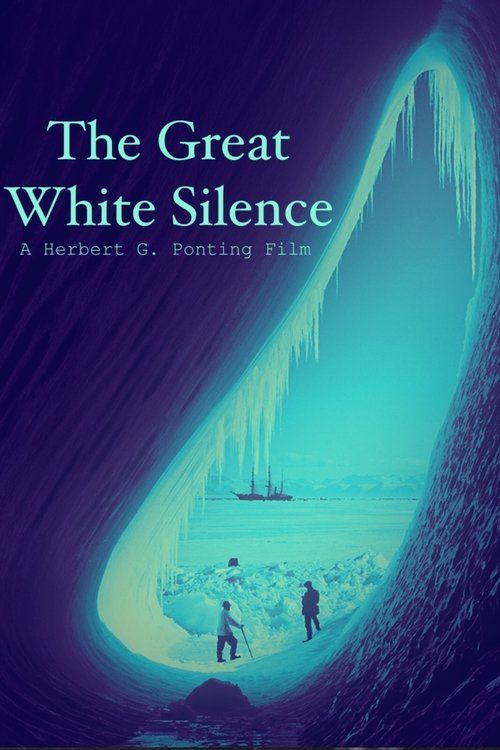

The Great White Silence

"The Epic Story of Captain Scott's Last Expedition"

Plot

Herbert G. Ponting documents Captain Robert Falcon Scott's Terra Nova Expedition to Antarctica, capturing stunning footage of the journey to the South Pole. The film follows the British expedition team from their departure in 1910, through their establishment of base camp at Cape Evans, and the grueling trek toward the pole. Ponting's camera records the daily life of the explorers, the breathtaking Antarctic landscape, and the scientific work conducted during the expedition. The documentary chronicles Scott's race against Roald Amundsen to reach the South Pole, culminating in the British team's arrival only to find the Norwegian flag already flying. The film concludes with the tragic fate of Scott and his four companions, who perished on their return journey, making this both a visual record of exploration and a memorial to one of history's most famous polar expeditions.

About the Production

Ponting used a specially adapted Newman & Sinclair camera with hand-cranked mechanism, designed to function in extreme cold. He brought over 30,000 feet of film stock and had to develop footage in a makeshift darkroom heated by blubber lamps. The camera equipment weighed over 100 pounds and had to be transported by sledge. Ponting left the expedition before the final polar journey, so the last part of Scott's expedition was reconstructed using photographs and Scott's diary entries. The original 1912 version was silent with intertitles, while the 1924 version featured new intertitles and a more dramatic narrative structure.

Historical Background

The film was created during the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration (1897-1922), when nations raced to explore the last unknown continent. This period saw intense competition between Britain and Norway for polar supremacy. The Terra Nova Expedition represented Edwardian Britain's imperial ambitions and scientific curiosity. The original footage was captured just before World War I, which would soon end the era of gentleman explorers. When Ponting re-released the film in 1924, the world had changed dramatically - the war had shattered Victorian values, and Scott's tragic sacrifice took on new meaning as a symbol of British endurance and noble failure. The film's release coincided with a growing public fascination with polar exploration and the dawn of the documentary film movement.

Why This Film Matters

The Great White Silence stands as a pioneering work in documentary filmmaking, representing one of the earliest examples of observational cinema. Ponting's approach of capturing daily life rather than staged events influenced generations of documentary filmmakers. The film established many conventions of expedition documentaries that continue today. Its preservation of a lost moment in exploration history makes it invaluable as both cinema and historical record. The film helped create the mythic status of Captain Scott in British culture, shaping how subsequent generations viewed polar exploration. Its restoration and re-release in 2011 demonstrated the enduring power of silent cinema and the continued relevance of early documentary techniques. The film's blend of scientific observation and emotional storytelling created a template for nature documentaries that would evolve into modern environmental cinema.

Making Of

Herbert Ponting, a successful professional photographer in his 40s, convinced Scott to let him join the expedition as official cinematographer after showing him his work from Japan. He underwent extensive training in cold weather survival and spent months testing his equipment in cold chambers. During filming, Ponting developed innovative techniques including using mirrors to bounce light into dark crevasses and building special igloo-like structures to protect his cameras. He left the expedition in early 1912, before the final polar journey, as planned, but maintained correspondence with Scott. After learning of the tragedy, Ponting dedicated the rest of his life to preserving the expedition's memory through lectures and films. The 1924 re-edit took him years to complete, as he struggled with the emotional weight of presenting his friends' final journey.

Visual Style

Ponting's cinematography was revolutionary for its time, employing techniques that would become standard in documentary filmmaking. He used natural light to capture the ethereal beauty of Antarctic landscapes, creating images that were both scientific documents and works of art. His compositions demonstrate a painter's eye, with careful attention to the relationship between humans and the overwhelming scale of the polar environment. He pioneered time-lapse photography to show the movement of ice and changing light conditions. The film features remarkable close-ups of wildlife, including penguins and seals, captured with unprecedented intimacy. Ponting's use of contrast between the white landscape and dark expedition clothing creates striking visual compositions. His camera work manages to convey both the beauty and danger of Antarctica, making the environment itself a character in the narrative.

Innovations

Ponting achieved several technical breakthroughs in extreme condition cinematography. He developed special camera housings that prevented frost from forming on lenses and used chemical treatments to keep film from becoming brittle in the cold. His darkroom techniques allowed him to process film in temperatures below freezing, a remarkable feat for the era. The film represents one of the earliest uses of the Newman & Sinclair camera, which was more portable than contemporary equipment. Ponting's lighting innovations, including the use of snow reflectors and filtered light, allowed him to capture clear images in the challenging Antarctic conditions. The preservation of the original nitrate film stock for over a century is itself a technical achievement. The 2011 digital restoration used state-of-the-art technology to repair damage while maintaining the original aesthetic, representing a bridge between early film technology and modern preservation techniques.

Music

The original 1924 release was accompanied by live musical performance, typically a piano or small orchestra following cue sheets provided by the distributor. The score combined popular classical pieces with original compositions to match the film's dramatic arc. For the 2011 restoration, composer Simon Fisher Turner created a new score that blended electronic elements with field recordings from modern Antarctic expeditions. This innovative approach connected the historical footage with contemporary environmental concerns. The restored version also includes period-appropriate sound effects like wind and ice cracking, carefully synchronized to enhance the viewing experience while maintaining the film's documentary integrity. The musical choices in both versions reflect the changing cultural context of how we view polar exploration - from heroic adventure to environmental concern.

Famous Quotes

"Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority." - Captain Scott's diary entry, shown in the film

"The Ponting pictures are a magnificent record of the expedition's work." - The Times review, 1924

"I do not know what to think of it all, but I think I have made a success of the photography." - Herbert Ponting's diary

"These pictures are not only a record of a great adventure, but a work of art." - Contemporary review

"The camera has captured the soul of the Antarctic." - Kathleen Scott on viewing the footage

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the Terra Nova ship breaking through Antarctic ice, establishing the scale and danger of the expedition

- The haunting footage of Scott and his team setting up the final camp before their polar journey, knowing they would never return

- The remarkable close-up sequences of Emperor penguins, showing Ponting's innovative approach to wildlife photography

- The time-lapse photography of the midnight sun moving around the horizon, demonstrating the unique polar phenomena

- The final scenes showing the memorial cross erected on Observation Hill, with Scott's name and those of his companions

Did You Know?

- Herbert Ponting was one of the first professional photographers to accompany a polar expedition and was paid £1,000 for his services

- The film contains the only known moving images of Captain Robert Falcon Scott

- Ponting's camera had to be modified with special lubricants that wouldn't freeze in temperatures reaching -50°C

- The original footage was shot between 1910-1912, making it one of the earliest feature-length documentaries

- Scott's widow, Kathleen Scott, helped Ponting re-edit the film for the 1924 release

- The film was restored by the British Film Institute in 2011 with a new musical score by Simon Fisher Turner

- Ponting brought a cinematograph to show films to the expedition members during the long Antarctic winter

- The expedition members nicknamed Ponting 'The Camera' due to his constant filming

- Some footage was lost when the ship Terra Nova was damaged in ice, but most negatives survived

- The film was initially called 'With Captain Scott, R.N. to the South Pole' when first shown in 1912

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in 1924 praised the film's technical achievements and emotional power. The Times called it 'a remarkable testament to human endurance and photographic skill.' Modern critics have recognized it as a masterpiece of early documentary filmmaking. The Guardian's review of the 2011 restoration described it as 'breathtakingly beautiful and profoundly moving.' Film historians consider it ahead of its time in its cinematic techniques and narrative structure. The British Film Institute cites it as 'perhaps the greatest of all Antarctic films' and a crucial work in documentary history. Critics consistently note how Ponting's background in art photography influenced the film's striking compositions and use of light in the extreme Antarctic environment.

What Audiences Thought

The 1924 release was well-received by British audiences who were still fascinated by Scott's expedition a decade after the tragedy. The film played to packed houses in London and was particularly popular with scientific societies and exploration clubs. When the restored version was released in 2011, it found a new audience and received standing ovations at film festivals. Modern viewers have been struck by the film's immediacy and the haunting quality of seeing the doomed explorers alive on screen. The film has developed a cult following among documentary enthusiasts and polar exploration fans. Online ratings and reviews consistently praise its historical importance and visual beauty, with many noting how it transcends its documentary nature to become a profound meditation on human ambition and mortality.

Awards & Recognition

- National Film Registry - Inducted 2011 (Library of Congress)

- British Film Institute - Named one of the 100 Greatest British Films

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Nanook of the North (1922)

- Work of Eadweard Muybridge

- Victorian expedition photography

- Early travelogues

- Scientific documentation films

This Film Influenced

- South (1930)

- The Lost World (1925)

- Kon-Tiki (1950)

- Man of Aran (1934)

- March of the Penguins (2005)

- Encounters at the End of the World (2007)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is well-preserved through the efforts of the British Film Institute National Archive. The original nitrate negatives survived in remarkably good condition and were used for the 2011 digital restoration. The BFI completed a comprehensive restoration in 2010-2011, scanning the original nitrate materials at 2K resolution and performing extensive digital cleanup. The restored version premiered at the London Film Festival in 2011. Both the 1912 and 1924 versions exist in various archives worldwide. The film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry in 2011, recognizing its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. The restoration project included creating new intertitles based on Ponting's original scripts and commissioning a new musical score.