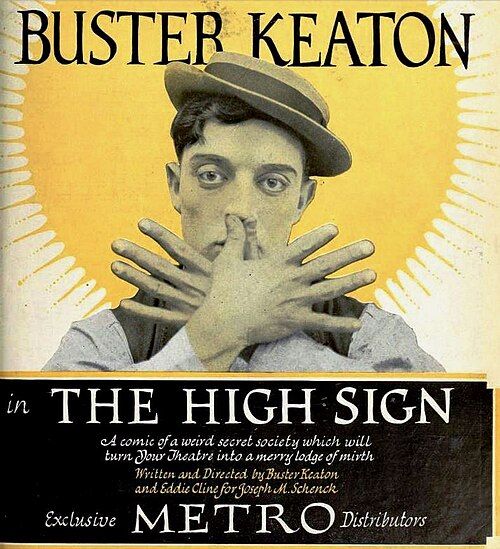

The High Sign

Plot

Buster Keaton plays a drifter who gets thrown off a train near an amusement park and stumbles into a job at a shooting gallery run by the Blinking Buzzards gang. Unbeknownst to him, the gang tests his shooting skills and hires him as a hitman to assassinate a wealthy businessman. When Buster discovers his target has a beautiful daughter, he has a change of heart and decides to protect the family instead by outfitting their mansion with an elaborate series of booby traps and defense mechanisms. The film culminates in a spectacular sequence where Buster uses his Rube Goldberg-like contraptions to single-handedly defeat the entire gang, demonstrating his trademark blend of physical comedy and mechanical ingenuity.

About the Production

The film was actually completed in 1920 but Keaton held it back from release for nearly a year because he felt it wasn't strong enough to follow his previous hit 'The Scarecrow.' The elaborate house defense sequence required weeks of preparation and engineering, with Keaton personally designing many of the mechanical gags. The train sequence at the beginning involved Keaton actually being thrown from a moving train onto a mattress just out of camera range.

Historical Background

The High Sign was produced during a transitional period in American cinema when the industry was shifting from short films to features. The early 1920s saw the rise of organized crime in public consciousness following Prohibition, making gangster themes popular in entertainment. The film also reflected the post-WWI fascination with secret societies and fraternal organizations. This was during Buster Keaton's peak creative period, as he was establishing himself as an independent filmmaker after working with Roscoe 'Fatty' Arbuckle. The amusement park setting mirrored the growing popularity of such venues in the 1920s, representing the era's expanding leisure culture. The film's mechanical gags and contraptions also reflected the technological optimism of the Jazz Age, when Americans were fascinated by new inventions and mechanical devices.

Why This Film Matters

'The High Sign' represents a pinnacle of silent comedy and showcases Buster Keaton's unique contribution to cinematic art. His innovative use of mechanical gags and physical comedy influenced generations of filmmakers and comedians. The film's elaborate house defense sequence became a template for similar scenes in countless later comedies, demonstrating how Keaton's work transcended its era. The movie exemplifies the sophistication of visual storytelling in silent cinema, proving that complex narratives could be told without dialogue. Keaton's character - the lovable underdog who outsmarts stronger opponents through cleverness and ingenuity - became an archetypal figure in American comedy. The film also represents the golden age of short comedies, which were crucial training grounds for filmmakers transitioning to features. Its preservation and continued study highlight the importance of silent film in the development of cinematic language and comedy techniques.

Making Of

The production of 'The High Sign' showcased Buster Keaton's meticulous approach to filmmaking and his hands-on involvement in every aspect. Keaton co-directed with Edward F. Cline, though Keaton was the creative driving force. He spent considerable time designing and building the elaborate booby trap mechanisms for the house defense sequence, working with carpenters and prop men to ensure each gag would work reliably. The shooting gallery scenes required precise coordination, with Keaton practicing extensively to perform convincing trick shots. The film's delay in release was due to Keaton's dissatisfaction with the initial cut, leading him to rework several sequences. This perfectionism was characteristic of Keaton's work ethic and contributed to his reputation as one of cinema's great innovators. The collaboration with Cline was part of Keaton's successful creative partnership during his peak years, with Cline understanding Keaton's vision and helping execute his complex physical comedy sequences.

Visual Style

The cinematography, typical of the era, primarily used static camera positions but with careful composition to showcase the physical gags. The film employs medium shots that allow full view of Keaton's athletic movements, while wider shots capture the scope of the elaborate mechanical sequences. The shooting gallery scenes use interesting angles to emphasize the skill involved in the trick shots. The house defense sequence required precise framing to coordinate multiple gags happening simultaneously across different parts of the set. The lighting enhances the dramatic effect of the night sequences during the climax. While not technically innovative by modern standards, the cinematography effectively serves the comedy by ensuring every gag is clearly visible and timed for maximum impact.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement is the complex house defense mechanism sequence, involving multiple interconnected gags that operate in precise succession. This required innovative engineering and careful choreography to ensure each mechanical device triggered correctly while maintaining comedic timing. The train sequence at the beginning employed practical effects with Keaton actually being thrown from a moving train, demonstrating early stunt coordination techniques. The shooting gallery scenes featured convincing trick shots achieved through careful camera placement and prop manipulation. The film also showcases Keaton's pioneering use of architectural space for comedy, transforming the house itself into a character through its mechanical defenses. These technical innovations influenced the development of physical comedy and action sequences in cinema for decades to come.

Music

As a silent film, 'The High Sign' was originally accompanied by live musical performances in theaters, typically featuring piano or organ accompaniment. The score would have been compiled from popular classical pieces and stock music appropriate to the action on screen. Modern restorations feature newly composed scores by silent film specialists, with some versions using period-appropriate ragtime and jazz music that reflects the film's 1920s setting. The musical accompaniment enhances the comedy by punctuating physical gags and building tension during the action sequences. Some contemporary screenings feature live musicians performing original compositions that highlight the film's mechanical themes and rhythmic comedy.

Famous Quotes

(Title card) 'Help Wanted - A Dead Shot'

(Title card) 'The High Sign - Secret Signal of the Blinking Buzzards'

(Title card) 'Hired to do a job - but the wrong job'

(Title card) 'A house protected by every modern invention except a burglar alarm'

Memorable Scenes

- The elaborate house defense sequence where Keaton uses interconnected booby traps including trapdoors, revolving walls, and mechanical devices to systematically defeat each gang member, culminating in a spectacular finale where multiple gags operate simultaneously in perfect comedic timing

Did You Know?

- The title 'The High Sign' refers to a secret gang signal used in the film, parodying the fascination with secret societies in post-WWI America

- This was one of the rare occasions where Keaton played a character initially willing to be a criminal, showing his versatility beyond innocent roles

- The film's famous house defense sequence with interconnected booby traps took over two weeks to film and required precise timing for each gag

- Bartine Burkett, who played the daughter, was one of Keaton's favorite leading ladies and appeared in several of his films

- The shooting gallery was filmed at a real amusement park, with Keaton performing his own trick shots

- Keaton performed all his own stunts, including a dangerous fall from a second-story window during the climax

- The Blinking Buzzards gang name was a comedic take on secret societies like the Ku Klux Klan and Masonic orders

- This film was originally intended to be Keaton's first independent production but was held back when he completed 'The Scarecrow' first

- The mechanical house gags influenced countless later films, most notably the 'Home Alone' series

- Keaton's perfectionism led him to reshoot several sequences multiple times until the timing was exactly right

- The film features one of Keaton's most famous recurring gags: the use of a newspaper to hide from pursuers

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'The High Sign' for Keaton's athletic ability and inventive gags, with Variety noting his 'remarkable agility and comic timing.' The film was particularly lauded for its elaborate mechanical sequences, which reviewers found both hilarious and impressive in their complexity. Modern critics consider it one of Keaton's finest two-reelers, with the house defense sequence often cited as a masterpiece of physical comedy. Film historian Kevin Brownlow called it 'a perfect example of Keaton's mechanical genius,' while The New York Times retrospective on silent comedies highlighted its 'breathtaking stunt work and ingenious plotting.' The film is frequently included in lists of greatest short comedies, and the house sequence is studied in film schools as an example of perfect comedic timing and visual storytelling.

What Audiences Thought

The film was highly popular with audiences in 1921, who were captivated by Keaton's death-defying stunts and clever gags. Theater owners reported strong attendance, particularly for repeat viewings of the spectacular house defense sequence. Contemporary audience letters to film magazines praised Keaton's 'daring and humor,' with many expressing amazement at his willingness to perform dangerous stunts. The film's popularity helped solidify Keaton's status as a major comedy star capable of carrying films independently. In subsequent decades, the film has maintained its appeal through theatrical revivals and home video releases, with modern audiences still finding the physical comedy and mechanical ingenuity entertaining. The house defense sequence continues to generate laughter and applause in contemporary screenings, proving the timelessness of Keaton's comic vision.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Works of Charlie Chaplin (particularly in physical comedy style)

- Keystone comedies (for slapstick foundation)

- Harold Lloyd's daredevil comedy style

- Contemporary fascination with secret societies and organized crime

- Méliès's mechanical fantasy films

- American vaudeville tradition

This Film Influenced

- Home Alone series (particularly the house defense sequences)

- The Naked Gun films (for physical comedy style)

- Jackie Chan's action comedies (for combination of stunts and humor)

- The Three Stooges shorts (for physical gag execution)

- Modern action comedies featuring elaborate traps and contraptions

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is well-preserved and has been restored by various archives including the Library of Congress and The Criterion Collection. It exists in complete form with good image quality, and multiple restored versions are available for viewing and study.