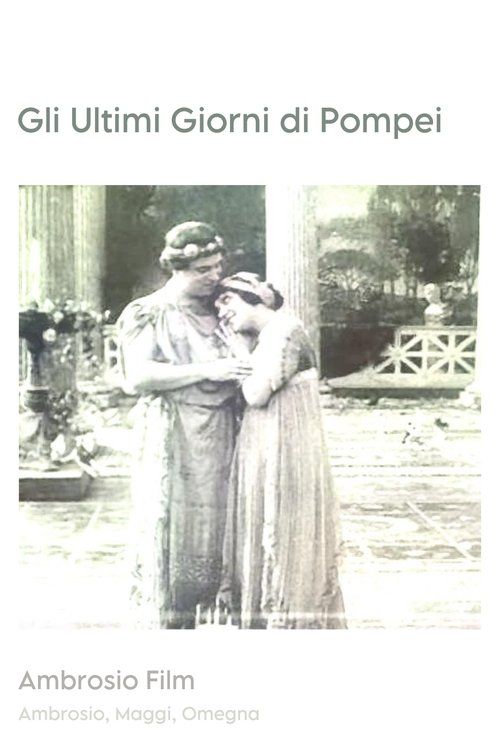

The Last Days of Pompeii

Plot

Set in Pompeii in 79 AD, days before the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius, this epic drama follows the tragic love story of Glaucus and Jone. Their romance is threatened by Arbaces, the powerful Egyptian High Priest who desires Jone for himself and will stop at nothing to possess her. Glaucus, showing compassion, purchases Nydia, a blind slave girl who has suffered greatly, but Nydia develops an obsessive love for her new master. Desperate to win Glaucus's affection, Nydia seeks help from Arbaces, who deceitfully gives her what she believes is a love potion but is actually a poison that will drive Glaucus to violent insanity. As these personal dramas unfold, the ominous rumblings of Vesuvius grow stronger, foreshadowing the imminent destruction that will consume them all and preserve their stories in volcanic ash for eternity.

About the Production

This film was one of the most ambitious productions of its time, featuring elaborate sets and a large cast of extras. The volcanic eruption sequence was particularly innovative for 1908, using special effects including smoke, fire, and falling debris to create the illusion of the disaster. The production required the construction of detailed replicas of ancient Roman streets and buildings, which were then systematically destroyed during the filming of the climax. Director Luigi Maggi also starred in the film, a common practice in early cinema when directors often doubled as actors due to limited personnel and the experimental nature of the medium.

Historical Background

The 1908 production of 'The Last Days of Pompeii' emerged during a pivotal period in cinema history when films were transitioning from simple novelty acts to sophisticated storytelling mediums. Italy was establishing itself as a leader in the emerging film industry, with Turin becoming an early center of production alongside Milan and Rome. This period saw the birth of the feature film and the development of more complex narrative structures. The film also reflected the growing public fascination with archaeology and ancient history, fueled by recent discoveries and excavations at sites like Pompeii itself. The choice of subject matter was particularly relevant as the ruins of Pompeii had become a major tourist attraction and symbol of classical antiquity's grandeur and fragility. Additionally, 1908 was a year of significant technological advancement in film, with improvements in camera stability, film stock quality, and editing techniques that made more ambitious productions possible.

Why This Film Matters

'The Last Days of Pompeii' holds a crucial place in film history as one of the earliest examples of the historical epic genre that would later become synonymous with Italian cinema. The film demonstrated that cinema could tackle complex historical narratives and spectacular visual effects, paving the way for later Italian masterpieces like 'Cabiria' (1914) and 'Quo Vadis' (1913). It helped establish the template for disaster films, showing how personal drama could be effectively set against catastrophic events. The film also contributed to the popularization of ancient Roman settings in cinema, creating a visual language for depicting antiquity that would influence filmmakers for decades. Its commercial success proved that audiences would respond to ambitious, expensive productions, encouraging investment in more elaborate films. The adaptation of a well-known literary work also helped legitimize cinema as a serious art form capable of handling complex literary adaptations, not just simple comic scenarios or actualities.

Making Of

The production of 'The Last Days of Pompeii' represented a significant leap forward in cinematic ambition for 1908. Director Luigi Maggi and his team at Ambrosio Film constructed elaborate sets in their Turin studios to recreate the streets and buildings of ancient Pompeii. The volcanic eruption sequence required considerable ingenuity, as filmmakers had to create convincing disaster effects without modern technology. They used combinations of smoke machines, controlled fires, and the deliberate destruction of sets to simulate the cataclysm. The casting was also notable for the era, with professional actors rather than theatrical performers, which was still relatively new in cinema. Maggi's decision to both direct and star in the film reflected the multi-tasking nature of early filmmaking, where personnel often wore multiple hats due to limited resources and the experimental nature of the medium. The film's success helped establish Ambrosio Film as a leading producer of spectacular films in early Italian cinema.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'The Last Days of Pompeii' was innovative for its time, utilizing techniques that were cutting-edge in 1908. The camera work was relatively static, as was common in the era, but the composition of shots showed careful planning to capture the scale of the sets and crowd scenes. The eruption sequence employed multiple camera angles to show the disaster from different perspectives, a technique that was still experimental. The film made effective use of depth in its staging, creating layered compositions that added visual interest to the Roman street scenes. Lighting was used dramatically, particularly in the climactic sequences where the glow of the volcanic eruption provided natural dramatic contrast. The cinematographer employed early special effects techniques such as multiple exposure and matte shots to create the illusion of the volcanic ash and falling debris. While the film stock of 1908 limited the visual quality by modern standards, the surviving footage shows a clear understanding of visual storytelling and the effective use of the camera to convey both intimate moments and epic scale.

Innovations

The film featured several technical innovations that were significant for 1908. The volcanic eruption sequence represented a major achievement in special effects, combining practical effects including controlled fires, smoke machines, and the systematic destruction of elaborate sets. The production utilized advanced set construction techniques for the time, creating detailed replicas of ancient Roman architecture that could be convincingly destroyed on camera. The film also employed early editing techniques to create tension and pace, particularly in the climax where cross-cutting between different characters' fates during the disaster heightened the drama. The use of multiple camera positions for the eruption sequence was technically ambitious for the period. The production also demonstrated advances in crowd management, coordinating large groups of extras to create the impression of a bustling ancient city. These technical achievements helped establish new standards for what was possible in cinema and influenced subsequent disaster films and historical epics.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Last Days of Pompeii' had no synchronized soundtrack, but would have been accompanied by live musical performance during exhibition. The typical presentation would have featured a pianist or small orchestra providing musical accompaniment tailored to the action on screen. For a dramatic film of this nature, the music would have ranged from romantic themes during the love scenes to dramatic, percussive passages during the eruption sequence. Theaters might have used cue sheets provided by the distributor or relied on the musicians' improvisation skills. Some upscale theaters may have even compiled specific classical pieces to accompany the film, choosing works that evoked ancient Rome or dramatic catastrophe. The emotional impact of the film relied heavily on this musical accompaniment to guide audience reactions and enhance the dramatic moments. The absence of dialogue meant that intertitles were used sparingly, with the visual storytelling and musical score carrying most of the narrative weight.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, the dialogue was conveyed through intertitles and pantomime rather than spoken quotes

Memorable Scenes

- The volcanic eruption sequence, which featured innovative special effects including fire, smoke, and the destruction of elaborate sets; The blind slave Nydia's emotional scenes, which were particularly praised by contemporary audiences; The dramatic confrontation between Glaucus and Arbaces; The final moments as the characters face their fate beneath the falling ash and debris; The opening scenes establishing the bustling life of Pompeii before the disaster

Did You Know?

- This was one of the earliest film adaptations of Edward Bulwer-Lytton's 1834 novel 'The Last Days of Pompeii'

- The film was produced by Ambrosio Film, one of Italy's first and most important early film studios

- Director Luigi Maggi not only directed but also starred in the film as Glaucus

- The eruption sequence used innovative special effects for its time, including miniature sets and pyrotechnics

- This film helped establish Italy as a major force in early epic filmmaking, predating the more famous Italian epics like 'Cabiria' (1914)

- The blind slave character Nydia became particularly popular with audiences and was featured prominently in marketing materials

- Only fragments of the original film are known to survive today, making it a partially lost film

- The production utilized over 100 extras for crowd scenes, an unusually large number for 1908

- The film's success led to numerous other adaptations of the Pompeii story in subsequent decades

- It was one of the first films to attempt a historical recreation of an ancient disaster on such a scale

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its ambitious scope and spectacular effects, particularly noting the impressive recreation of the volcanic eruption. The film was reviewed favorably in trade publications of the era, with special mention given to its elaborate sets and the convincing nature of the disaster sequences. Critics of the time were impressed by the film's length and complexity, which exceeded the typical one-reel format common in 1908. Modern film historians and critics view the film as an important milestone in early cinema, recognizing it as a precursor to the epic films that would dominate Italian cinema in the following decade. While some modern critics note the film's primitive techniques by contemporary standards, they acknowledge its historical importance and innovative spirit. The surviving fragments continue to be studied by film scholars as examples of early special effects techniques and narrative development in cinema's first decade.

What Audiences Thought

The film was reportedly very popular with audiences of its time, drawing crowds to cinemas eager to see the spectacular disaster sequences. Audiences were particularly impressed by the volcanic eruption, which represented one of the most elaborate special effects sequences yet seen in cinema. The romantic elements of the story resonated with viewers, and the character of Nydia, the blind slave, proved especially popular. The film's success led to increased demand for historical epics and disaster films, influencing the programming choices of cinema owners across Europe and America. Contemporary accounts suggest that the film was often advertised as a 'sensation' or 'marvel' of cinema, emphasizing its spectacular elements to attract audiences. The popularity of the film also sparked interest in the original novel by Bulwer-Lytton, demonstrating cinema's ability to drive interest back to literary sources. Audience reaction helped establish the commercial viability of longer, more elaborate films, encouraging producers to invest in increasingly ambitious projects.

Awards & Recognition

- None - formal film awards did not exist in 1908

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Edward Bulwer-Lytton's 1834 novel 'The Last Days of Pompeii'

- Earlier Italian historical films

- Stage adaptations of the novel

- Contemporary interest in archaeology and classical antiquity

- The tradition of grand opera with its themes of love, betrayal, and catastrophe

This Film Influenced

- 'The Last Days of Pompeii' (1913)

- 'The Last Days of Pompeii' (1926)

- 'The Last Days of Pompeii' (1935)

- 'The Last Days of Pompeii' (1959)

- 'Quo Vadis' (1913)

- 'Cabiria' (1914)

- Later Italian historical epics

- Early disaster films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially lost - only fragments and sequences survive today. Some portions are preserved in film archives including the Cineteca Italiana in Milan and the British Film Institute. The surviving footage has been restored and preserved on digital formats, but significant portions of the original film are believed to be lost forever. The incomplete nature of the surviving material makes it difficult to experience the film as originally intended, though the existing fragments provide valuable insight into early Italian cinema and the development of the historical epic genre.