The Lion of the Moguls

Plot

In the exotic kingdom of the Moguls, Prince Roudghito-Sing serves as a young officer in the royal palace when he becomes captivated by Zemgali, a beautiful captive princess imprisoned by the Grand Khan who desires her for himself. When their forbidden love is discovered, the prince must flee his homeland, eventually finding refuge in Paris where his striking appearance and exotic demeanor lead to his discovery by a French film company. Hired as an actor, Roudghito-Sing becomes the object of affection for Anna, the film's leading lady, which creates tension with banker Morel, both the film's producer and Anna's possessive lover. As the production continues, the prince must navigate the dangerous waters of romantic jealousy while maintaining his disguise and protecting his true identity, all while the memory of his beloved Zemgali continues to haunt him from afar.

About the Production

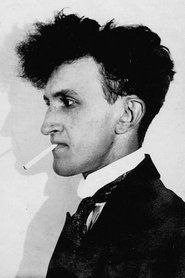

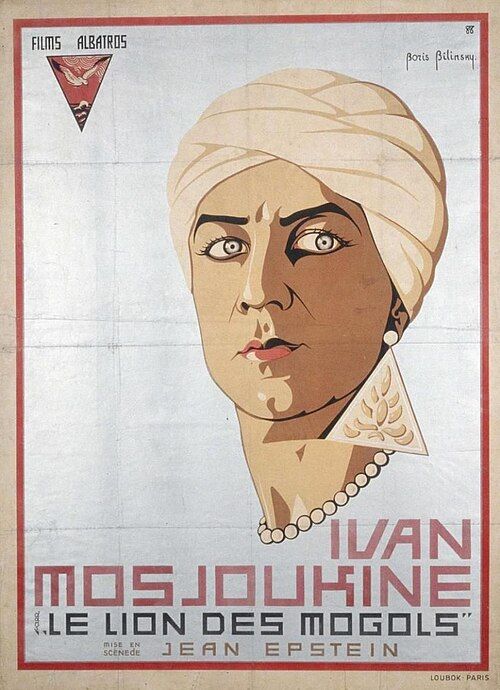

The Lion of the Moguls was produced by Films Albatros, a company founded by Russian émigré filmmakers who had fled the Russian Revolution. The film represents a collaboration between French avant-garde director Jean Epstein and the Russian film community in Paris, particularly featuring Ivan Mosjoukine, one of the most celebrated Russian actors of the silent era. The production utilized elaborate sets and costumes to create the exotic Mogul setting, contrasting it with the modern Parisian film studio environment. The film was part of a series of exotic, romantic productions that were popular in European cinema during the 1920s.

Historical Background

The Lion of the Moguls was produced during a fascinating period in French cinema history (1924), when the French film industry was recovering from World War I and experiencing an artistic renaissance. This era saw the emergence of the French avant-garde movement, with directors like Jean Epstein, Abel Gance, and Marcel L'Herbier pushing the boundaries of cinematic expression. The film also reflects the significant impact of Russian émigrés on French cinema following the 1917 Revolution, with many talented Russian actors, directors, and technicians establishing themselves in Paris. The 1920s was a decade of international co-productions and cultural exchange in European cinema, with films frequently featuring exotic settings and cross-cultural themes. The popularity of orientalist narratives during this period reflected Western fascination with Eastern cultures, though often through romanticized and stereotypical lenses. The film industry was also transitioning from shorter programs to feature-length productions, and The Lion of the Moguls, with its 86-minute runtime, represents this shift toward more substantial cinematic experiences.

Why This Film Matters

The Lion of the Moguls represents an important cultural intersection in European cinema, showcasing the collaboration between French avant-garde sensibilities and Russian dramatic traditions. The film contributed to the development of the exotic romance genre in European cinema, which would continue to influence filmmakers throughout the 1920s and beyond. Ivan Mosjoukine's performance in this film exemplifies the transition from the theatrical acting style of early cinema to the more subtle, psychologically nuanced performances that would become standard in later silent films. The movie-within-a-movie structure was innovative for its time, prefiguring later meta-cinematic works. The film also serves as a testament to the cultural diaspora's impact on artistic development, demonstrating how displaced Russian filmmakers enriched French cinema with their unique perspectives and techniques. Today, the film is studied as an example of cross-cultural artistic collaboration and as a representative work of both Epstein's oeuvre and the Russian émigré film movement in Paris.

Making Of

The production of The Lion of the Moguls brought together two distinct cinematic traditions: the French avant-garde and Russian émigré filmmaking. Jean Epstein, known for his theoretical writings on cinema and experimental techniques, worked with Ivan Mosjoukine, who brought the dramatic intensity and emotional expressiveness characteristic of Russian silent cinema. The film was shot at the Albatros studios, which had become a creative hub for Russian filmmakers in exile. The elaborate Mogul palace sets required extensive construction and were designed to create an authentic exotic atmosphere while being practical for filming. The casting of real-life couple Mosjoukine and Lissenko added authenticity to their on-screen chemistry. The film's production coincided with a period of intense creative activity in Paris, where filmmakers from various nationalities were experimenting with new cinematic techniques and narrative approaches. The movie-within-a-movie elements allowed Epstein to explore meta-cinematic themes while maintaining the commercial appeal of the romantic storyline.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Lion of the Moguls, while the specific cinematographer is not definitively recorded in available sources, reflects the sophisticated visual style characteristic of French avant-garde cinema of the 1920s. The film employs dramatic lighting contrasts between the exotic, shadow-filled interiors of the Mogul palace and the brighter, more modern settings of the Paris film studio. The camera work includes the kind of dynamic movements and innovative angles that Jean Epstein championed in his theoretical writings about cinema. The visual composition emphasizes the emotional states of the characters through careful framing and the use of light and shadow. The film's cinematography successfully creates two distinct visual worlds - the mysterious, sensual East and the industrial, modern West - reinforcing the narrative's thematic contrasts.

Innovations

The Lion of the Moguls demonstrates several technical achievements typical of sophisticated French cinema of the mid-1920s. The film's elaborate set construction for the Mogul palace scenes represents advanced production design capabilities of the period. The movie-within-a-movie structure required careful technical planning to distinguish between the 'real' narrative and the film being made within the story. The lighting techniques used to create the contrasting atmospheres of the exotic and modern settings show the growing sophistication of cinematographic art in this era. The film also makes effective use of location shooting and studio work, combining these elements seamlessly. While not revolutionary in its technical aspects, the film represents the high level of craftsmanship that had become standard in major French productions by 1924.

Music

As a silent film, The Lion of the Moguls would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The specific musical scores used are not documented in available sources, but typical practice would have involved either a full orchestra in major cinemas or a pianist or small ensemble in smaller venues. The music would have been chosen to enhance the exotic setting of the Mogul sequences and the romantic tension of the narrative. Modern screenings of restored versions often feature newly composed scores that attempt to capture the film's dual cultural influences, combining elements that suggest both Eastern and Western musical traditions. The absence of recorded sound makes the film particularly dependent on visual storytelling and the expressive performances of its actors.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, famous quotes are not documented in intertitle form in available sources

The film's power lies in its visual storytelling and Mosjoukine's expressive performance rather than written dialogue

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic escape of Prince Roudghito-Sing from the Mogul palace, showcasing Mosjoukine's athletic performance and the film's elaborate set design

- The prince's arrival in Paris and discovery by the film company, highlighting the cultural contrast between East and West

- The tense confrontation scenes between the prince, Anna, and the jealous banker Morel on the film set

- The romantic sequences between the prince and Princess Zemgali in the Mogul palace, emphasizing the exotic atmosphere and forbidden nature of their love

Did You Know?

- Ivan Mosjoukine, who plays Prince Roudghito-Sing, was one of the highest-paid actors in European cinema during the 1920s and was known for his incredibly expressive face and intense performances

- Director Jean Epstein was a prominent figure in the French avant-garde film movement and developed theories about 'photogénie' - the unique quality that cinema could bring to subjects

- The film was produced by Films Albatros, a company comprised largely of Russian émigrés who had established themselves in Paris after fleeing the Bolshevik Revolution

- Mosjoukine was so popular that his name alone could guarantee international distribution for films, particularly in Germany and the Soviet Union

- The exotic setting and romantic plot were typical of the popular 'orientalist' genre in European cinema of the 1920s

- The film's dual setting - the exotic East and modern Paris - reflected the fascination with cultural contrasts that characterized many European films of this period

- Nathalie Lissenko, who plays Zemgali, was Mosjoukine's real-life wife and frequent co-star

- The film was one of several collaborations between Epstein and the Russian émigré film community in Paris

- The movie-within-a-movie structure was relatively innovative for its time, commenting on the nature of filmmaking itself

- The film's preservation status makes it a rare example of Epstein's work from this period

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised The Lion of the Moguls for its visual beauty and Mosjoukine's powerful performance, with French film journals highlighting the film's successful blend of exotic spectacle and emotional depth. The film was particularly noted for its effective use of contrast between the Mogul and Parisian settings, which critics felt enhanced the dramatic tension. Modern film historians and critics view the film as an important example of Franco-Russian cinematic collaboration and as a significant work in Jean Epstein's filmography. Some contemporary reviewers have noted that while the plot follows conventional romantic melodrama patterns, Epstein's directorial techniques and Mosjoukine's performance elevate the material beyond its genre limitations. The film is often cited in studies of 1920s European cinema as an example of how international co-productions and cultural exchange enriched the art form during this period.

What Audiences Thought

The Lion of the Moguls was well-received by audiences in 1924, particularly those who were fans of Ivan Mosjoukine, whose star power guaranteed significant public interest. The exotic setting and romantic storyline appealed to contemporary audiences who were fascinated by orientalist themes and cross-cultural romance narratives. The film's success in France led to international distribution, particularly in countries where Russian émigré cinema had found appreciative audiences. Modern audiences who have had the opportunity to see restored versions of the film often comment on Mosjoukine's magnetic screen presence and the film's visual sophistication. The film continues to be screened at classic film festivals and cinematheques, where it is appreciated both as a historical artifact and as an entertaining example of 1920s European cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Russian silent cinema tradition

- French avant-garde film movement

- Orientalist literature and art

- German Expressionist cinema

- Hollywood exotic romance films

This Film Influenced

- Later French exotic romances

- Films about the film industry

- Works featuring cross-cultural romance themes

- Movies exploring meta-cinematic concepts

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Lion of the Moguls is considered a partially preserved film from the silent era. While not completely lost, complete prints are rare, with some sequences possibly missing or existing only in fragmentary form. The film has been preserved through the efforts of various film archives, particularly French cinematheques and institutions dedicated to preserving silent cinema. Restored versions have been assembled from available film elements, allowing modern audiences to experience this important work of Franco-Russian cinema collaboration. The preservation status highlights the ongoing challenges of maintaining access to films from the 1920s, many of which have been lost due to the volatile nature of early film stock.