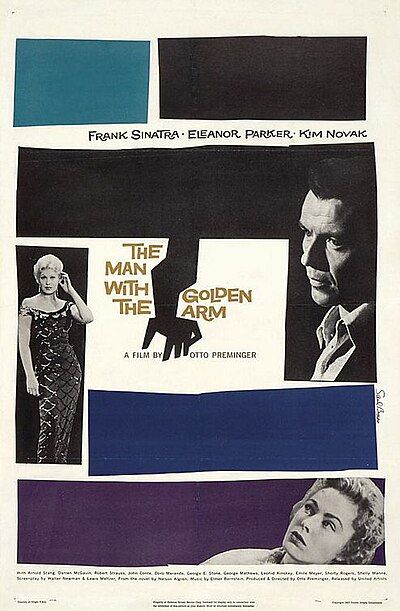

The Man with the Golden Arm

"The story of a man who wanted to clean up his own act!"

Plot

Frankie Machine, a skilled card dealer and heroin addict, returns to Chicago after serving six months in prison for a minor offense, determined to kick his drug habit and pursue his dream of becoming a professional jazz drummer. He moves back in with his wheelchair-bound wife Zoshe, who uses guilt and emotional manipulation to keep him dependent on her, while struggling to find legitimate work as a musician. Frankie's former employer and illegal card dealer, Schwiefka, tempts him back into the world of underground poker, where his 'golden arm' makes him valuable. Simultaneously, Frankie encounters his old drug pusher, 'Mouse', who relentlessly pursues him to reignite his heroin habit. Despite brief moments of hope and a budding romance with Molly, a kind-hearted neighbor, Frankie's world unravels as he succumbs to addiction, leading to a devastating downward spiral that culminates in a desperate struggle for redemption and survival.

About the Production

The film faced significant censorship challenges from the Production Code Administration due to its depiction of drug addiction. Otto Preminger fought extensively with the censors to include realistic portrayals of withdrawal and drug use. The controversial subject matter led to the film being denied the Production Code seal initially, but Preminger released it anyway, forcing the industry to reconsider its standards. Frank Sinatra prepared for his role by visiting rehabilitation centers and speaking with former addicts, though he insisted on not trying heroin himself. The drumming sequences were performed by professional jazz drummer Shelly Manne, though Sinatra took extensive lessons to make his movements appear authentic.

Historical Background

Released in 1955, 'The Man with the Golden Arm' emerged during a transitional period in American cinema and society. The post-war era of the 1950s was characterized by conformity and optimism on the surface, but beneath lay growing social tensions and awareness of urban problems. The film's production coincided with the early Cold War period, when American society was particularly concerned with maintaining a positive image abroad. Drug addiction was considered a taboo subject, rarely discussed openly in mainstream media. The film's release came just as the Hollywood studio system was beginning to crumble, and independent producers like Preminger were gaining more creative freedom. The mid-1950s also saw the rise of method acting, with performers like Marlon Brando and James Dean bringing new levels of psychological realism to their roles. Sinatra's performance in this film represented a mature departure from his earlier, lighter roles and reflected the growing sophistication of American acting.

Why This Film Matters

The cultural impact of 'The Man with the Golden Arm' cannot be overstated, as it fundamentally changed Hollywood's approach to controversial subject matter. The film broke the long-standing taboo against depicting drug addiction in mainstream cinema, paving the way for more realistic portrayals of social problems. Its success challenged the Production Code's authority and contributed significantly to its eventual replacement by the MPAA rating system in 1968. The movie also marked a turning point in Frank Sinatra's career, transforming his image from a light entertainer to a serious dramatic actor capable of handling complex, dark material. The film's jazz score and urban aesthetic influenced a generation of filmmakers and helped establish the visual and auditory language for urban dramas. Its portrayal of addiction as a disease rather than a moral failing was progressive for its time and influenced public discourse on substance abuse. The film's commercial success proved that audiences were ready for more mature, challenging content, encouraging studios to take risks on controversial projects.

Making Of

The production of 'The Man with the Golden Arm' was marked by significant controversy and innovation. Director Otto Preminger, known for pushing boundaries, engaged in a prolonged battle with the Production Code Administration over the film's depiction of drug addiction. The Hays Code had strictly prohibited showing drug use, but Preminger refused to compromise his vision, eventually releasing the film without the Code's seal of approval. This bold move forced the industry to reconsider its censorship standards. Frank Sinatra, deeply committed to the role, lost weight and studied the mannerisms of addicts, though he drew the line at experiencing drug use himself. The casting of Kim Novak as Molly was controversial, as she was a relative newcomer discovered in a television commercial. The film's innovative opening sequence, designed by Saul Bass, featured animated paper cutouts forming a hypodermic needle and arm, setting a new standard for title design. The jazz score by Elmer Bernstein was groundbreaking, using dissonant chords and improvisational elements to reflect Frankie's internal struggles and the urban environment.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Sam Leavitt employed stark, high-contrast black-and-white photography that emphasized the gritty urban environment and Frankie's psychological isolation. The film used innovative camera techniques, including Dutch angles and disorienting compositions during Frankie's drug withdrawal sequences to visually represent his internal turmoil. Leavitt utilized deep focus photography to create a sense of urban claustrophobia, often trapping characters within architectural frames. The lighting design was particularly notable for its use of harsh shadows and expressionistic techniques, especially in the drug dealer's apartment and during the poker games. The camera work during the drumming sequences employed dynamic movement and close-ups to convey the energy and passion of Frankie's musical aspirations. The visual style drew heavily from film noir traditions while pushing them into more psychologically complex territory, creating a visual language that would influence urban dramas for decades.

Innovations

The film featured several technical innovations that were groundbreaking for 1955. The opening title sequence, designed by Saul Bass, revolutionized film title design with its animated paper cutouts forming symbolic imagery. The production employed innovative sound recording techniques for the drumming sequences, using multiple microphones to capture the full range of percussion sounds. The film's special effects for depicting drug withdrawal, while subtle by today's standards, were accomplished through clever camera work, editing, and performance rather than obvious optical effects. The makeup department created realistic effects for Frankie's physical deterioration during addiction sequences. The film's editing, particularly during the poker games and withdrawal scenes, used rapid cutting and jump cuts to create psychological tension and disorientation. The production also pioneered new techniques for filming in confined spaces, using custom-built camera mounts to capture intimate scenes in small apartments and rooms.

Music

Elmer Bernstein's jazz-influenced score was revolutionary for its time, breaking away from traditional Hollywood orchestral arrangements to create something more contemporary and urban. The main theme featured dissonant brass and walking bass lines that reflected the film's gritty setting and Frankie's internal conflicts. Bernstein incorporated elements of cool jazz and bebop, which were at the height of their popularity in 1955, giving the film an authentic contemporary sound. The drumming sequences featured actual jazz recordings, with Shelly Manne's performance providing the musical backbone for Frankie's character. The score used leitmotifs for different characters - smooth, seductive themes for Molly, harsh, discordant passages for 'Mouse', and melancholic strings for Zoshe. The soundtrack was released as an album and became a commercial success, helping to popularize jazz scores in Hollywood films. Bernstein's innovative approach to film scoring influenced countless composers and helped establish jazz as a legitimate genre for dramatic cinema.

Famous Quotes

You got a date with a hypodermic needle, Frankie. Don't be late.

I'm not a junkie. I'm a musician.

That's the trouble with you, Zoshe. You think a wheelchair is a license to be cruel.

A man's got to have a code, a creed to live by.

You're a card player, Frankie. You know when to hold 'em and when to fold 'em.

Music is the only thing that's real. The only thing that matters.

I'm trying to get straight, Molly. I'm trying to get clean.

In this world, you either get tough or you get dead.

The past is a ghost that haunts us all.

Every time I think I'm out, they pull me back in.

Memorable Scenes

- The harrowing withdrawal sequence where Frankie experiences delirium tremens, using distorted camera angles and rapid editing to convey his physical and psychological agony.

- The opening title sequence with Saul Bass's innovative animated paper arm forming a hypodermic needle, setting the tone for the entire film.

- The intense poker game scenes where Frankie's 'golden arm' skills are displayed, showcasing the tension and danger of his former life.

- Frankie's passionate drumming sequence where he loses himself in the music, representing his hope for redemption and artistic expression.

- The final confrontation scene where Frankie must choose between his old life and a chance at redemption, culminating in his desperate struggle to overcome his addiction.

Did You Know?

- This was the first major Hollywood film to explicitly deal with heroin addiction, breaking the Production Code's taboo against depicting drug use.

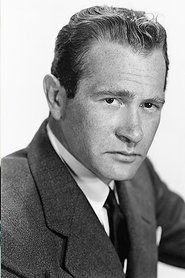

- Frank Sinatra was initially considered for the role of 'Mouse' the drug dealer, but campaigned to play Frankie Machine instead.

- The controversial film led to the revision of the Production Code, allowing more realistic depictions of social problems in cinema.

- Kim Novak was discovered by Columbia Pictures head Harry Cohn in a TV commercial and was cast despite having little acting experience.

- The film's opening credits featured innovative Saul Bass-designed animation with a paper arm that was considered revolutionary for its time.

- Frank Sinatra's performance earned him an Academy Award nomination, though he famously threw the Oscar statue he won for 'From Here to Eternity' out his hotel window when he didn't win for this film.

- The drumming heard in the film was performed by jazz legend Shelly Manne, who was paid $5,000 for his work.

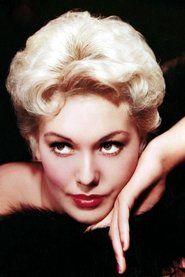

- Eleanor Parker wore a special corset and was trained to move as if she had a genuine disability for her role as the wheelchair-bound wife.

- The film was banned in several cities and countries upon release due to its controversial subject matter.

- Otto Preminger fought the censors for over a year to get the film approved, eventually securing a special exception to the Production Code.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was largely positive, with many reviewers praising the film's courage in tackling such a controversial subject. The New York Times' Bosley Crowther called it 'a powerful and compelling film' and particularly lauded Sinatra's performance as 'the best work of his career.' Variety noted that the film 'packs a wallop' and described it as 'a grim, realistic, and hard-hitting drama.' Some critics, however, felt the film was too melodramatic or that it romanticized addiction. Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a groundbreaking classic that pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable in mainstream cinema. It currently holds an 82% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, with critics consensus calling it 'a brave, bold film that features a career-defining performance from Frank Sinatra.' The film is frequently cited in film studies as a pivotal work in the decline of the Production Code and the rise of more realistic American cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1955 was mixed but generally positive, with the film performing well at the box office despite its controversial subject matter. Many viewers were shocked by the film's frank depiction of drug addiction, something rarely seen in mainstream entertainment of the era. The film's release without the Production Code seal generated significant publicity and curiosity, drawing audiences who wanted to see what the censors had banned. Sinatra's popularity undoubtedly contributed to the film's commercial success, with many of his fans eager to see him in such a dramatically different role. Some audience members found the film too intense or depressing, while others praised its realism and courage. Over time, the film has gained a reputation as a classic, particularly among film enthusiasts and Sinatra fans. Modern audiences often express surprise at how ahead of its time the film was in its approach to addiction and its refusal to sugarcoat difficult subject matter.

Awards & Recognition

- Golden Globe Award for Best Actor - Motion Picture Drama (Frank Sinatra)

- New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress (Eleanor Parker)

- Venice Film Festival Volpi Cup for Best Actor (Frank Sinatra)

- National Board of Review Award for Best Film

- Directors Guild of America Award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures (Otto Preminger - nominated)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Lost Weekend (1945) - for its portrayal of addiction

- On the Waterfront (1954) - for its urban realism and moral complexity

- Italian neorealism films - for their gritty depiction of urban life

- Film noir tradition - for its visual style and themes of alienation

This Film Influenced

- The Hustler (1961) - for its portrayal of addiction and talent

- Midnight Cowboy (1969) - for its urban grit and character study

- The French Connection (1971) - for its realistic drug depiction

- Requiem for a Dream (2000) - for its unflinching look at addiction

- The Wrestler (2008) - for its portrait of an artist struggling with personal demons

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the Academy Film Archive and the Library of Congress. In 2019, it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being 'culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.' The film has undergone digital restoration and is available in high-definition formats. Original negatives and elements are maintained in studio archives, and the film has been preserved in both 35mm and digital formats for future generations.