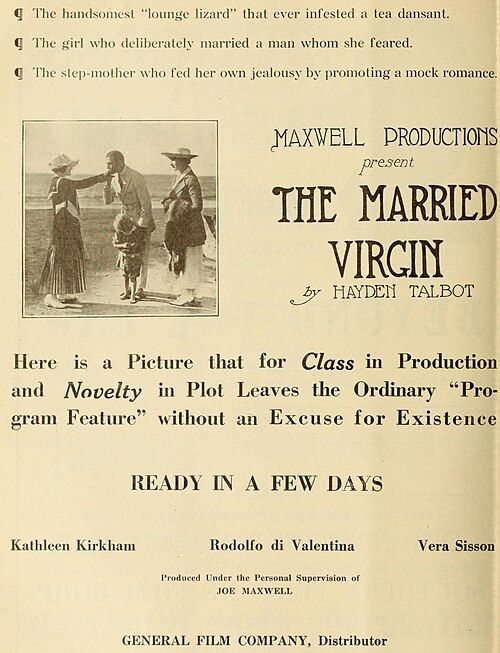

The Married Virgin

Plot

In this dramatic silent film, a wealthy businessman named Robert McKeever finds himself blackmailed by the handsome but unscrupulous Count Roberto di San Fraccini, who threatens to expose a scandalous secret from McKeever's past. To save her father from disgrace and potential imprisonment, his innocent daughter Patricia agrees to marry the Count, believing she can control the situation through her virtue and determination. However, the marriage proves to be a nightmare as the Count continues his manipulative ways, attempting to seduce Patricia's friend while maintaining his hold over the family through blackmail. The situation reaches its climax when Patricia's true love, a young doctor named Douglas McKee, returns from abroad and discovers the truth behind the arranged marriage, leading to a dramatic confrontation that exposes the Count's villainy. Ultimately, Patricia must find the strength to break free from her disastrous marriage and reclaim her life while saving her family's honor.

About the Production

The film was produced during the transitional period of American cinema when features were becoming the standard over short films. It was one of several films Rudolph Valentino made for Fox before his breakthrough stardom. The production utilized the relatively new technique of indoor lighting setups to create dramatic shadows, reflecting the growing sophistication of film cinematography in the late 1910s. The film's title was somewhat misleading for marketing purposes, as the 'virgin' aspect was more symbolic than literal, referring to the heroine's innocence rather than her physical state.

Historical Background

The Married Virgin was produced in 1918, during the final year of World War I, a period that profoundly shaped American society and cinema. The film industry was undergoing significant transformation, with Hollywood establishing itself as the global center of film production. This era saw the consolidation of the studio system, with major companies like Fox Film Corporation (the film's distributor) gaining increasing control over production, distribution, and exhibition. The war had accelerated the decline of European film industries, creating opportunities for American cinema to dominate international markets. Socially, 1918 was a time of changing moral standards and gender roles, with women having recently gained the right to vote in some states and the 'New Woman' emerging as a cultural archetype. The film's themes of female autonomy, sexual politics, and family honor reflected these societal tensions. The Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 also affected film production and exhibition, though the industry proved resilient. Technologically, cinema was evolving from primitive one-reel shorts to more sophisticated feature films with complex narratives and cinematic techniques.

Why This Film Matters

The Married Virgin holds particular cultural significance as one of the few surviving examples of Rudolph Valentino's work before he became an international superstar with 'The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse' in 1921. The film provides valuable insight into Valentino's early career and the types of roles he played before being typecast as the romantic 'Latin Lover.' Its exploration of themes such as blackmail, arranged marriage, and female agency reflects the changing social mores of the late 1910s, particularly regarding women's autonomy and sexuality. The film's survival is culturally important because most of Valentino's early work has been lost, making this a crucial document for film historians and scholars studying his development as an actor. Additionally, the film represents an example of the transition from short films to features in American cinema, showcasing the narrative complexity and production values that were becoming standard in the industry. The film's re-release in 1924 under the title 'Frivolous Wives' demonstrates how early Hollywood practices of recycling and repackaging content to capitalize on star power, a practice that continues in the industry today.

Making Of

The production of 'The Married Virgin' took place during a pivotal moment in Hollywood's transition from short films to feature-length productions. The film was shot on location in Los Angeles, utilizing the growing studio infrastructure that was transforming the area into the entertainment capital. Rudolph Valentino, still relatively unknown at the time, was cast against type as the villainous Count, a role that allowed him to demonstrate his range beyond the romantic characters for which he would later become famous. The cast and crew worked under the direction of Joseph De Grasse (using the pseudonym Joseph Maxwell), who was known for his efficient shooting methods and ability to complete productions quickly and economically. The film's production faced the typical challenges of the silent era, including the need for exaggerated acting styles to convey emotion without dialogue and the technical limitations of early camera equipment. Despite these constraints, the production team managed to create a visually compelling drama that utilized the latest techniques in lighting and composition to enhance the story's emotional impact.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Married Virgin reflects the evolving visual sophistication of late 1910s American cinema. The film employed the emerging use of dramatic lighting to create mood and emphasize emotional moments, particularly in scenes involving blackmail and intimate confrontations. The camera work was relatively static by modern standards but showed the influence of German Expressionist techniques that were beginning to influence American filmmakers. The use of shadows and light was particularly notable in scenes featuring Valentino's villainous character, with cinematographers utilizing chiaroscuro effects to visually represent his moral ambiguity. The film's visual composition followed the standard practices of the period, with balanced framing and careful attention to the placement of actors within the frame to convey their relationships and power dynamics. Interior scenes were shot using the latest artificial lighting techniques of the time, allowing for more controlled and dramatic effects than natural lighting could provide. The cinematography also made effective use of location shooting in Los Angeles, incorporating both studio sets and real locations to create a more authentic visual environment for the story.

Innovations

The Married Virgin demonstrated several technical achievements typical of the evolving film industry of the late 1910s. The film utilized the increasingly sophisticated artificial lighting techniques that were revolutionizing indoor filmmaking, allowing for greater control over mood and atmosphere. The production employed multiple camera setups for different angles within scenes, a technique that was becoming more common as filmmakers discovered the narrative power of varied perspectives. The film's editing showed growing sophistication in the use of cross-cutting to build tension and parallel action, particularly effective in the blackmail and confrontation sequences. The makeup techniques used in the film, especially for Valentino's character, reflected the advancing artistry of cinematic makeup that was moving beyond theatrical conventions to create more subtle and camera-appropriate effects. The film's preservation, despite the fragility of nitrate film stock from this period, represents an achievement in itself, allowing modern audiences to experience this piece of cinema history. While not groundbreaking in its technical innovations, the film represents the solid craftsmanship and technical competence that had become standard in American feature filmmaking by 1918.

Music

As a silent film, The Married Virgin did not have an original synchronized soundtrack, but would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. Typical accompaniment for a film of this type in 1918 would have included a piano player or small orchestra in larger theaters, performing a combination of classical pieces, popular songs of the era, and original improvisations. The music would have been carefully chosen to match the mood of each scene, with romantic themes for the love scenes, dramatic and tense music for the blackmail sequences, and triumphant music for the resolution. The film's distributors would have provided cue sheets to theater musicians, suggesting appropriate pieces for different moments in the film. Modern screenings of restored silent films like this one often feature newly composed scores by contemporary musicians specializing in silent film accompaniment, or historically appropriate compilations of period music. The lack of original recorded soundtrack makes it impossible to know exactly what music audiences heard in 1918, but the practice of musical accompaniment was essential to the silent film experience, providing emotional context and narrative guidance for viewers.

Famous Quotes

I married you to save my father's honor, but I will not sacrifice my soul to keep yours intact.

A man who preys on the weakness of others is no man at all.

In this world of shadows and lies, the truth is the most dangerous weapon of all.

Love cannot be bought or sold, only given freely or stolen by force.

When honor is at stake, even the innocent must make impossible choices.

Memorable Scenes

- The tense blackmail scene where the Count reveals his hold over Patricia's father, showcasing Valentino's menacing screen presence and the dramatic lighting that emphasizes the moral darkness of the situation.

- The wedding ceremony where Patricia's internal conflict is conveyed through subtle facial expressions and body language, demonstrating the sophisticated acting techniques emerging in silent cinema.

- The climactic confrontation scene where all the characters' secrets are revealed, featuring dynamic cross-cutting between characters and heightened emotional performances that exemplify the melodramatic style of the era.

Did You Know?

- This was one of Rudolph Valentino's earliest surviving film appearances, made three years before his breakthrough role in 'The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse'

- The film was originally titled 'The Married Virgin' but was later re-released as 'Frivolous Wives' in 1924 to capitalize on Valentino's posthumous fame

- Rudolph Valentino played a villainous character, a rare occurrence in his career before he became a romantic leading man

- The film was considered lost for decades before a copy was discovered and preserved by the Museum of Modern Art

- Director Joseph Maxwell was actually a pseudonym for Joseph De Grasse, a prolific director of the silent era

- The film's themes of blackmail and arranged marriage were quite controversial for 1918, pushing the boundaries of what was acceptable in mainstream cinema

- Vera Sisson, who played the lead, was a popular actress of the 1910s but retired from acting shortly after this film

- The film's running time of 50 minutes was typical for features of this period, as longer epics had not yet become the industry standard

- Frank Newburg, who played the romantic lead, was actually a stage actor making one of his few film appearances

- The film's preservation status makes it one of the few surviving examples of Valentino's early work before he became a superstar

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of The Married Virgin was modest, with reviewers of the time acknowledging it as a competent melodrama but not recognizing it as particularly exceptional. The film trade publications of 1918 gave it standard positive notices, praising the performances and the dramatic tension but not singling it out for special acclaim. Modern critics and film historians have reassessed the film primarily through the lens of Rudolph Valentino's career, viewing it as an important early work that demonstrates his range beyond his later typecasting. Film scholars have noted that the movie's themes and narrative structure were representative of the melodramatic conventions of the late silent era, while also acknowledging its slightly more sophisticated approach to moral ambiguity compared to many contemporaneous productions. The preservation of the film has allowed modern critics to appreciate its technical merits and its place in the evolution of American feature filmmaking, though it is generally regarded more as a historical curiosity than a masterpiece of silent cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception to The Married Virgin in 1918 was generally positive, though not enthusiastic enough to make it a major box office success. Contemporary moviegoers would have been drawn to the film's dramatic storyline and the rising popularity of feature-length melodramas. The film's themes of family honor, blackmail, and romantic intrigue resonated with audiences of the period, who were accustomed to moral tales with clear distinctions between virtue and villainy. Rudolph Valentino's performance, while not yet star-making, would have been noted by attentive viewers for its intensity and screen presence. Following Valentino's explosion into superstardom in 1921, the film was re-released in 1924 under the title 'Frivolous Wives' to capitalize on his posthumous fame after his tragic death in 1926. Modern audiences, primarily classic film enthusiasts and Valentino scholars, have shown interest in the film as a historical artifact that provides insight into the early career of one of cinema's first true male sex symbols. The film's preservation has allowed contemporary audiences to appreciate Valentino's versatility in playing a villainous role, contrasting sharply with his later romantic image.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- European melodramatic traditions

- 19th century novels of social scandal

- Earlier American silent melodramas

- Theatrical conventions of the period

- Contemporary social issues regarding women's rights

This Film Influenced

- Later Valentino vehicles that typecast him as a romantic lead

- 1920s melodramas exploring similar themes of blackmail and family honor

- Early Hollywood films dealing with sexual politics and female agency

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Married Virgin is partially preserved, with surviving elements held in film archives including the Museum of Modern Art in New York. While not completely intact, enough of the film survives to provide a comprehensive viewing experience. The film was considered lost for many years before being rediscovered and preserved, making it one of the few surviving examples of Rudolph Valentino's early work. The surviving elements have been restored and are available for viewing by film scholars and through specialized classic film venues. The preservation status is significant given the high rate of loss for films from this period, with estimates suggesting that over 75% of American silent films have been lost forever.