The Soul of Youth

"A Story of the Street Kid Who Found a Home in the Heart of a Man of Affairs"

Plot

The Soul of Youth tells the story of Ed Simpson, a rebellious young boy who has spent his formative years in an orphanage where his mischievous behavior constantly lands him in trouble. Frustrated with institutional life, Ed escapes to the streets where he quickly learns the harsh realities of urban survival through his friendship with Mike, an experienced newsboy who becomes his mentor. Despite Mike's guidance, Ed's street-smart but naive nature leads him into legal trouble, culminating in a court appearance where his fate hangs in the balance. The presiding judge, recognizing the boy's potential beneath his rough exterior, decides to give him a second chance by arranging for his adoption by a young, idealistic politician. This new relationship offers Ed the opportunity for redemption and a legitimate path forward, though the film explores whether his street instincts and institutional upbringing can truly be overcome by the promise of a better life.

About the Production

The Soul of Youth was produced during the transition period when Paramount Pictures was establishing itself as a major studio. William Desmond Taylor, already an established director by 1920, brought his characteristic attention to social issues to this production. The film featured extensive location shooting in downtown Los Angeles to capture authentic urban street life, which was relatively uncommon for the era. The production utilized real newsboys and street children as extras to enhance the authenticity of the street scenes.

Historical Background

The Soul of Youth was produced in 1920, a pivotal year in American history marked by the aftermath of World War I, the beginning of Prohibition, and significant social reform movements. The film emerged during the Progressive Era's final phase, when issues like child welfare, juvenile justice, and urban poverty were at the forefront of national discourse. The early 1920s saw increased public awareness of institutional problems in orphanages and the juvenile court system, leading to reforms in child welfare policies. Hollywood was also transitioning from a cottage industry to a vertically integrated studio system, with films like this helping establish cinema as a legitimate medium for addressing social issues. The film's release coincided with the ratification of the 19th Amendment granting women's suffrage, reflecting the broader social changes occurring in American society. The post-war economic boom and migration to cities created new urban social problems that films like The Soul of Youth sought to document and address.

Why This Film Matters

The Soul of Youth represents an important early example of American cinema's engagement with social issues, particularly the welfare of disadvantaged children in urban environments. The film helped establish the 'problem picture' as a legitimate genre, demonstrating that movies could both entertain and educate audiences about contemporary social concerns. Its sympathetic portrayal of juvenile delinquents challenged prevailing attitudes about youth crime and institutionalization, contributing to public discourse on child welfare reform. The film's commercial success proved that audiences would respond to serious subject matter, encouraging other studios to produce socially relevant content. It also helped establish the trope of the redeemed street urchin that would become a staple of American cinema. The film's emphasis on second chances and rehabilitation over punishment reflected progressive ideas about criminal justice that would influence later films and social policy. Its realistic depiction of urban street life provided valuable historical documentation of early 20th-century American city life.

Making Of

The production of The Soul of Youth reflected William Desmond Taylor's growing interest in socially relevant cinema. Taylor, who had previously worked as a gold prospector and actor before becoming a director, brought a unique perspective to the material. The casting process was particularly thorough, with Taylor insisting on finding actors who could authentically portray the street-smart characters. Lewis Sargent was discovered after Taylor saw him in a small role in another film and was impressed by his naturalistic acting style. The film's street scenes were challenging to shoot, as Taylor insisted on filming in actual urban locations rather than on studio sets, requiring special permits and coordination with city authorities. The production team worked closely with local social service agencies to ensure accurate representation of the juvenile justice system. Lila Lee's involvement in the project was significant, as she was one of the few actresses of the era who had contractual approval over her projects and chose this film specifically because of its social message.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Soul of Youth, handled by Charles Rosher, employed a naturalistic style that was relatively innovative for its time. Rosher utilized extensive location photography in downtown Los Angeles, capturing authentic street scenes with a documentary-like quality that contrasted with the more artificial look of many studio-bound productions of the era. The film made effective use of natural lighting in exterior scenes, creating a gritty realism that enhanced the story's social commentary. The cinematography employed medium shots and close-ups to emphasize the emotional states of the characters, particularly the young protagonists, which was still a relatively new technique in 1920. The courtroom scenes used a static camera style that mirrored the formal proceedings, while the street sequences featured more dynamic camera movement to convey the chaos and energy of urban life. The visual contrast between the institutional orphanage, the chaotic streets, and the orderly politician's home was achieved through careful composition and lighting choices.

Innovations

The Soul of Youth employed several technical innovations that were relatively advanced for 1920. The film's extensive use of location shooting in urban environments was unusual for the period, when most productions were still primarily studio-bound. The production utilized early mobile camera equipment to capture street scenes with greater flexibility and movement than was typical. The film also made effective use of cross-cutting techniques to build tension during sequences showing parallel action in different locations. The lighting design, particularly in the street scenes, demonstrated sophisticated use of available light and artificial illumination to create atmospheric effects. The film's editing pace, while still following the slower rhythm of silent cinema, was more dynamic than many contemporary productions, particularly in the action sequences involving the newsboys.

Music

As a silent film, The Soul of Youth would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have been compiled from various classical pieces and popular songs of the era, selected to match the emotional tone of each scene. Orchestras in larger theaters would have performed adaptations of works by composers like Chopin for emotional moments, while smaller venues might have used a pianist or organist. The street scenes likely featured more upbeat, ragtime-influenced music, while the orphanage sequences would have been accompanied by somber, melancholic pieces. No original score was composed specifically for the film, which was standard practice for productions of this period. Modern screenings of restored versions typically feature newly commissioned scores or compilations of period-appropriate music.

Famous Quotes

"Every kid deserves a chance to be somebody, even if he starts from nowhere." - Judge to the politician

"The streets don't care if you're good or bad, they just care if you're smart enough to survive." - Mike to Ed

"You can take the boy out of the streets, but can you take the streets out of the boy?" - Court observer

"Institutional life teaches you to follow rules, but street life teaches you to break them." - Ed Simpson

"A politician's heart is no different from any other man's - it just has more doors to open." - News commentary

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the chaotic orphanage dining hall, where Ed's rebellious nature is first established through his refusal to eat institutional food and his subsequent escape through a window.

- The montage of Ed's first night on the streets, intercutting his loneliness and fear with the bustling nightlife of the city, culminating in his chance meeting with Mike.

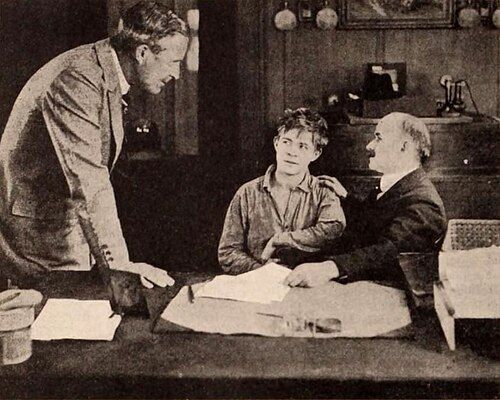

- The courtroom scene where the judge delivers his impassioned speech about youth rehabilitation, using close-ups to emphasize the emotional impact on both Ed and the politician.

- The newsboy training sequence where Mike teaches Ed the tricks of the trade, featuring authentic period newspaper sales techniques and street slang.

Did You Know?

- This film was one of the earliest to tackle the subject of juvenile delinquency and the orphanage system in American cinema.

- Director William Desmond Taylor was murdered just two years after this film's release, in 1922, in one of Hollywood's most famous unsolved crimes.

- Lewis Sargent, who played Ed, was actually a former newsboy himself before entering acting, bringing authentic experience to his role.

- The film was part of a series of social problem pictures that Paramount produced in the early 1920s to demonstrate cinema's educational potential.

- Lila Lee, who played the female lead, was one of Paramount's biggest stars at the time and was known as 'The Madonna of the Screen.'

- The film's original title was 'The Boy Who Wouldn't Stay Put' but was changed to 'The Soul of Youth' before release to sound more poetic.

- Ernest Butterworth Jr., who played Mike the newsboy, was only 12 years old during filming but already had over 20 film credits.

- The courtroom scenes were filmed on a set that was an exact replica of the Los Angeles juvenile court, adding to the film's realism.

- This film was considered quite progressive for its time in its sympathetic portrayal of troubled youth rather than condemning them.

- The film's success led to a wave of 'orphan pictures' throughout the 1920s, though few matched its social consciousness.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to The Soul of Youth was largely positive, with reviewers praising its social consciousness and authentic performances. The Motion Picture News called it 'a picture with a purpose' and commended William Desmond Taylor for 'treating a serious subject with the dignity it deserves.' Variety noted that 'while the picture may be too serious for those seeking mere entertainment, it will appeal to thinking patrons who appreciate cinema with a message.' Modern critics have recognized the film as an important early example of socially conscious American cinema. Film historian Kevin Brownlow has cited it as 'ahead of its time in its sympathetic treatment of juvenile delinquency.' The film is now regarded as a significant work in Taylor's filmography and an important document of early Hollywood's engagement with social issues, though it remains lesser-known than some of its contemporaries.

What Audiences Thought

The Soul of Youth performed well at the box office upon its release, particularly in urban areas where audiences could relate to its depiction of street life. Contemporary audience reports indicate that the film resonated strongly with working-class viewers and families who had experience with the juvenile system. Many reviews from the period mention that audiences were moved by the film's emotional core and its message of redemption. The film's success led to increased demand for similar 'problem pictures' from other studios. However, some rural audiences found the urban setting less relatable, and the film performed better in larger cities. The positive word-of-mouth from audiences helped sustain its run beyond the typical exhibition period of the era. Modern audiences who have seen the film through archival screenings have responded positively to its naturalistic acting style and surprisingly contemporary social commentary.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- D.W. Griffith's social dramas

- Contemporary progressive reform literature

- Charles Dickens' novels about orphaned children

- Early documentary films about urban life

- Stage melodramas dealing with social issues

This Film Influenced

- The Kid (1921)

- Little Annie Rooney (1925)

- The Rag Man (1925)

- Street Angel (1928)

- The Champ (1931)

- Boys Town (1938)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Soul of Youth is considered a partially lost film. While complete copies no longer exist in their original form, fragments and portions of the film survive in various archives. The Library of Congress holds approximately 20 minutes of footage, primarily from the first and third reels. The George Eastman Museum has additional fragments totaling about 10 minutes. Some scenes survive only in truncated form or as still photographs. The UCLA Film and Television Archive has been working to piece together the surviving elements, but a complete restoration has not been possible due to the incomplete nature of the surviving material. The film's status as partially lost makes it particularly valuable to film historians, as its surviving elements provide insight into early socially conscious American cinema and William Desmond Taylor's directorial style.