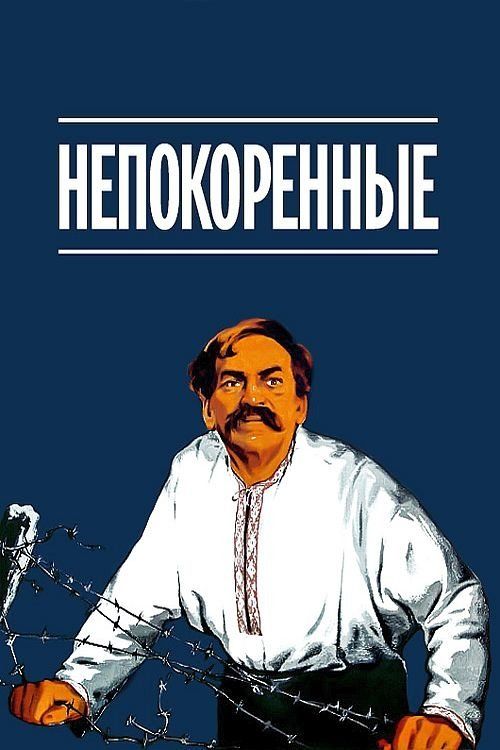

The Taras Family

Plot

Set in Nazi-occupied Kiev during World War II, The Taras Family follows the struggles of the Taras family and their neighbors as they resist German occupation. The Nazis attempt to force the reopening of a local munitions factory, putting pressure on Soviet workers to collaborate with the enemy. The family faces increasing hardships, separation, and the constant threat of violence as they maintain their loyalty to the Soviet cause. The film culminates in a harrowing sequence depicting the Nazi search for Jewish escapees and the brutal massacre at Babi Yar, one of the most infamous atrocities of the Holocaust. Despite the overwhelming darkness of their situation, the family's resilience and determination to remain unvanquished serves as a testament to the Soviet spirit during the Great Patriotic War.

About the Production

The film was shot immediately following the liberation of Kiev from Nazi occupation, allowing the filmmakers to use authentic locations that had recently witnessed the depicted events. The production faced significant challenges due to post-war resource shortages and the need to reconstruct damaged sets. The controversial Babi Yar sequence was filmed using documentary-style techniques that were revolutionary for Soviet cinema at the time, including hand-held cameras and rapid editing to create a sense of immediacy and chaos.

Historical Background

The Taras Family was produced during a critical period in Soviet history - the immediate aftermath of World War II, known in the USSR as the Great Patriotic War. The film was made when the full scale of Nazi atrocities in occupied Soviet territories was becoming known, and when the Soviet government was establishing its official narrative of the war. The film's production in 1944-1945 coincided with Stalin's tightening of cultural controls and the beginning of the post-war repression known as the Zhdanov Doctrine. Despite this, the film managed to address sensitive topics like the Holocaust and civilian suffering, though it did so within the framework of Soviet ideology. The film's release in 1945 came as the Soviet Union was transitioning from wartime to peacetime, and there was a pressing need to process the trauma of the war while maintaining the official narrative of Soviet victory and heroism. The depiction of Babi Yar was particularly significant, as it was one of the first times this massacre was addressed in Soviet cinema, despite the later Soviet suppression of Jewish aspects of the tragedy.

Why This Film Matters

The Taras Family holds a unique place in Soviet cinema as one of the earliest and most direct cinematic treatments of the Holocaust on Soviet territory. Its graphic depiction of the Babi Yar massacre was groundbreaking, though it would take decades for the full historical significance of this atrocity to be officially recognized in the Soviet Union. The film's innovative use of documentary-style techniques influenced later Soviet war films and helped establish a more realistic approach to depicting wartime atrocities. Its portrayal of civilian resistance and family endurance during occupation became a template for later Soviet war narratives. The film also represents an important moment in Ukrainian cinema, being produced at the Kiev Film Studio (later renamed Dovzhenko Film Studio) and featuring prominent Ukrainian actors. Despite being somewhat overshadowed in international cinema by more famous Soviet war films like 'The Cranes Are Flying,' The Taras Family is now recognized by film historians as a significant work that pushed the boundaries of what was possible in Soviet wartime cinema.

Making Of

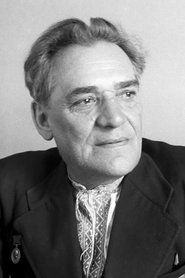

The production of The Taras Family began in the immediate aftermath of Kiev's liberation from Nazi occupation in November 1943. Director Mark Donskoy, deeply affected by the atrocities he witnessed, felt compelled to create a film that would bear witness to the suffering and resistance of the Soviet people. The casting process was particularly challenging as many actors had been displaced or killed during the occupation. Amvrosii Buchma, a legendary figure in Ukrainian theater and cinema, was persuaded to return from evacuation to play the patriarch of the Taras family. The most challenging aspect of production was the recreation of the Babi Yar massacre. Donskoy insisted on using documentary techniques, including hand-held cameras and natural lighting, to create an unflinching portrayal of the atrocity. This decision caused significant controversy within the Soviet film establishment, which preferred more heroic and less graphic depictions of war. The film crew worked under difficult conditions, with shortages of film stock and equipment, and often had to film in locations that were still damaged from the recent fighting. Despite these challenges, Donskoy's vision prevailed, resulting in one of the most powerful and controversial Soviet war films of the 1940s.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Taras Family, led by director of photography Yuri Yekelchik, was groundbreaking for its time. The film combines traditional Soviet socialist realist style with innovative documentary techniques. The Babi Yar sequence, in particular, features hand-held camera work, rapid editing, and natural lighting that creates a sense of immediacy and chaos rarely seen in Soviet cinema of the 1940s. Yekelchik used deep focus composition to capture the scale of the atrocities while maintaining intimate details of human suffering. The contrast between the relatively formal, composed shots of family life and the chaotic, almost vérité style of the massacre sequence creates a powerful emotional effect. The film also makes effective use of chiaroscuro lighting in the occupation scenes, emphasizing the darkness and moral ambiguity of the period. The cinematography was controversial at the time for its departure from conventional Soviet film aesthetics but is now recognized as technically innovative and emotionally effective.

Innovations

The Taras Family achieved several technical innovations that were ahead of their time in Soviet cinema. The most significant was the use of hand-held cameras for the Babi Yar sequence, a technique rarely used in Soviet films of the 1940s. This allowed for greater mobility and immediacy in capturing the chaos of the massacre. The film also pioneered rapid editing techniques for action sequences, creating a sense of urgency and disorientation that contrasted with the more measured pacing typical of Soviet cinema. The production team developed new methods for simulating large-scale crowd scenes with limited resources, using clever camera angles and editing to create the illusion of thousands of people. The film's sound design was also innovative, particularly in its use of silence during the massacre sequence rather than orchestral music. These technical achievements, while controversial at the time, influenced later Soviet war films and demonstrated Donskoy's willingness to push the boundaries of conventional Soviet filmmaking.

Music

The musical score for The Taras Family was composed by Herman Zhukovsky, a prominent Soviet composer known for his film music. The soundtrack combines traditional Ukrainian folk melodies with classical orchestral arrangements, reflecting the film's setting and themes. The music ranges from tender, melancholic themes during family scenes to dissonant, atonal passages during the Nazi occupation sequences. The Babi Yar massacre sequence is notable for its almost complete absence of music, relying instead on natural sounds and screams to create its devastating impact. This decision to use silence rather than orchestral manipulation was revolutionary for Soviet cinema of the period. The film also incorporates diegetic music, including songs sung by the characters that reinforce themes of resistance and hope. The soundtrack was released on vinyl in the Soviet Union and remains one of the most respected examples of wartime Soviet film composition.

Famous Quotes

Even in darkness, we must keep the light of humanity alive within us.

They can take our homes, but they cannot take our spirit.

To survive is not enough; we must remain human.

In times like these, family is the only fortress we have.

Every act of resistance, no matter how small, is a victory.

Memorable Scenes

- The Babi Yar massacre sequence - a harrowing 15-minute documentary-style depiction of the Nazi slaughter of Jewish civilians, notable for its graphic realism and innovative cinematography that uses hand-held cameras and rapid editing to create overwhelming chaos and horror.

- The family's final night together before separation - an intimate scene showing the Taras family sharing a meal while discussing their fears and hopes for the future.

- The factory confrontation - where Soviet workers must decide whether to collaborate with the Nazis or face the consequences.

- The search sequence - Nazis conducting a house-to-house search for Jewish escapees, building unbearable tension.

- The final resistance scene - showing the family's ultimate act of defiance against their oppressors.

Did You Know?

- The film's original Russian title 'Nepokorenniye' translates to 'The Unconquered' or 'The Unvanquished,' reflecting its central theme of resistance.

- Director Mark Donskoy was already famous for his Gorky Trilogy, establishing him as one of the Soviet Union's most respected filmmakers.

- The Babi Yar sequence was so graphically realistic that it was initially criticized by Soviet authorities for being too disturbing for audiences.

- The film was one of the first major Soviet productions to directly address the Holocaust and Nazi atrocities against Jewish civilians.

- Amvrosii Buchma, who played the lead role, was one of Ukraine's most celebrated actors and was later named a People's Artist of the USSR.

- Venyamin Zuskin, who co-starred in the film, was later arrested during Stalin's anti-Semitic campaign and died in a prison camp in 1953.

- The film's controversial documentary-style techniques in the massacre sequence were years ahead of their time and would later be recognized as innovative.

- The production used actual survivors of the Babi Yar massacre as consultants and extras to ensure authenticity.

- The film was briefly banned from international distribution due to its graphic content and political sensitivity.

- Director Donskoy faced criticism from Soviet film authorities for what they called 'formalist excesses' in his cinematographic choices.

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics were divided in their response to The Taras Family. While many praised its patriotic message and powerful performances, others criticized Donskoy's 'formalist' techniques, particularly in the Babi Yar sequence. The hand-held camera work and rapid editing were seen by conservative critics as excessive and contrary to the established Soviet aesthetic of socialist realism. Pravda, the official Soviet newspaper, gave the film a mixed review, acknowledging its emotional power while questioning its artistic choices. Western critics, when the film was eventually shown abroad, were impressed by its raw power and unflinching depiction of wartime atrocities, though some found it overly propagandistic. Modern film historians have reassessed the film more positively, recognizing its technical innovations and its importance as an early Holocaust documentary-drama. The Babi Yar sequence is now seen as remarkably ahead of its time in its cinematic approach to depicting mass violence.

What Audiences Thought

The Taras Family resonated deeply with Soviet audiences who had experienced the war firsthand. Many viewers found the film's depiction of occupation and resistance painfully authentic, and the Babi Yar sequence was particularly affecting for those who had lived through similar atrocities. The film was shown widely across the Soviet Union in 1945-1946 and drew large audiences, especially in Ukraine and other territories that had been under Nazi occupation. However, some audience members found the graphic content too disturbing, and there were reports of viewers leaving theaters during the massacre sequence. Despite these reactions, the film became part of the official canon of Soviet war cinema and was regularly shown on Soviet television on Victory Day anniversaries. In recent years, the film has been rediscovered by new audiences through film festivals and retrospectives of Soviet cinema, where it continues to provoke strong emotional responses.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, Second Class (1946) - Mark Donskoy (director)

- State Prize of the Ukrainian SSR (1946)

- Honored recognition at the Venice Film Festival (1946)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Sergei Eisenstein's montage techniques

- Italian neorealism (early influence)

- Documentary filmmaking of the 1930s

- Donskoy's earlier Gorky Trilogy

- Soviet socialist realist tradition

- German expressionist cinema (for depicting evil)

This Film Influenced

- The Cranes Are Flying (1957)

- Come and See (1985)

- Ordinary Fascism (1965)

- The Ascent (1977)

- Later Soviet Holocaust documentaries

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Taras Family has been preserved in the Russian State Film Archive (Gosfilmofond) and the Dovzhenko National Film Studio archives in Ukraine. The original nitrate negatives have been transferred to safety stock, and the film underwent restoration in the 1990s as part of a Soviet cinema preservation project. However, some sequences show signs of deterioration due to the poor storage conditions during the immediate post-war period. A digitally restored version was released in 2015 as part of a Mark Donskoy retrospective, though the restoration was limited by the condition of the surviving materials. The film is considered at-risk due to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, which has threatened film archives and cultural heritage sites.