The White-Haired Girl

"A tale of oppression and liberation that moved a nation"

Plot

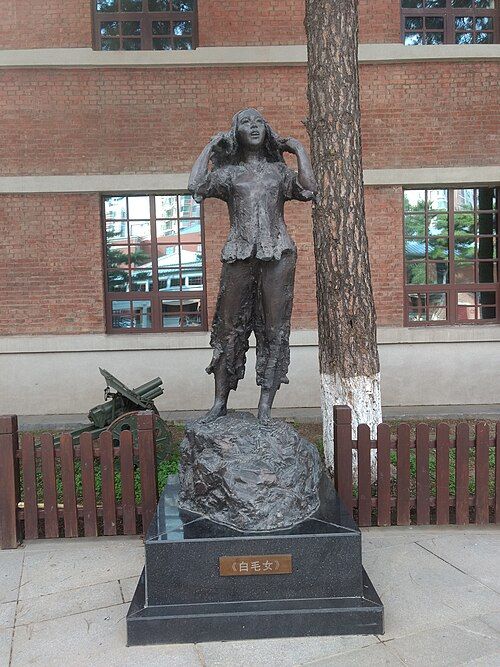

The White-Haired Girl tells the tragic story of Yang Bailao, a poor tenant farmer in rural China, and his beautiful daughter Xi'er. The despotic landlord Huang Shiren, coveting Xi'er, schemes to possess her by exploiting Yang's debts. On the eve of Chinese New Year, Huang forces Yang to sell his daughter as debt repayment, leading to Xi'er being taken to the landlord's mansion. After her father dies from grief and abuse, Xi'er endures horrific treatment and eventually escapes into the mountains, where years of hardship and isolation turn her hair white. She's eventually discovered by Communist guerrilla fighters who rescue her and help overthrow the oppressive landlord system, symbolizing the liberation of the Chinese peasantry.

About the Production

The film was adapted from the famous revolutionary opera of the same name, which itself was based on folk legends from the Taihang Mountains region. The production faced significant challenges in the early years of the People's Republic of China, including limited film stock and technical equipment. Director Wang Bin worked closely with the original opera creators to maintain the story's revolutionary spirit while adapting it for the cinematic medium.

Historical Background

The White-Haired Girl was produced during a crucial period of Chinese history - the early years of the People's Republic under Mao Zedong. The film served both as entertainment and as political education, reinforcing the Communist Party's narrative about the evils of the old feudal system and the necessity of revolution. Made just two years after the founding of the PRC, it was part of a broader cultural campaign to establish new revolutionary art forms that would serve the masses. The film's themes of class struggle and liberation resonated with audiences who had recently experienced or witnessed the social transformation of China. The production coincided with land reform campaigns across China, making its message particularly relevant and timely.

Why This Film Matters

The White-Haired Girl became one of the most influential films in Chinese cinema history, establishing many conventions for revolutionary filmmaking. The character of Xi'er entered Chinese popular culture as a symbol of female resilience and revolutionary spirit. The film's success demonstrated the power of cinema as a tool for political education and social mobilization. It influenced generations of Chinese filmmakers and set standards for how class struggle could be portrayed dramatically and emotionally. The story's adaptation across multiple media - opera, film, ballet, and later television - demonstrated its enduring cultural resonance. The film also helped establish the template for the 'model opera' works that would dominate Chinese culture during the Cultural Revolution.

Making Of

The production of The White-Haired Girl was a monumental undertaking in the early years of the People's Republic. The film industry was still reorganizing after the civil war, and resources were extremely limited. Director Wang Bin had to work with primitive equipment and often filmed using natural lighting due to electricity shortages. The casting process was rigorous, with Tian Hua selected from hundreds of applicants to play Xi'er. The production team conducted extensive research in rural villages to ensure authenticity in depicting peasant life. Many of the supporting actors were actual peasants and workers, reflecting the new socialist approach to casting. The film's musical elements were carefully adapted from the original opera, with composers working to translate the stage score for cinematic presentation.

Visual Style

The cinematography, led by Wu Yinxian, employed techniques influenced by Soviet socialist realism while incorporating elements of traditional Chinese visual aesthetics. The film used dramatic lighting contrasts to emphasize the moral divide between oppressed peasants and cruel landlords. The mountain sequences where Xi'er lives in exile were particularly striking, using wide shots to emphasize her isolation and the harshness of nature. The camera work during the New Year scene employed intimate close-ups to capture the family's brief moments of happiness before tragedy strikes. The visual style evolved from dark, claustrophobic compositions during the oppression sequences to bright, open framings during the liberation scenes.

Innovations

For its time, the film achieved several technical milestones in Chinese cinema. The makeup effects for Xi'er's transformation to white hair were particularly innovative, using techniques developed specifically for the production. The sound recording overcame significant technical limitations to capture both dialogue and musical numbers clearly. The film's special effects, while modest by modern standards, effectively conveyed dramatic moments like the storm sequences. The production team developed new methods for location shooting in difficult terrain, establishing techniques that would be used in subsequent Chinese films. The editing successfully balanced the musical and dramatic elements, maintaining narrative momentum while allowing for emotional moments.

Music

The film's music was adapted from the original revolutionary opera by composers including Ma Ke and Zhang Lu. The soundtrack blended traditional Chinese folk melodies with Western orchestral arrangements, creating a distinctive revolutionary musical style. Key songs like 'The North Wind Blows' and 'I Am the White-Haired Girl' became classics of Chinese revolutionary music. The score effectively used leitmotifs to represent different characters and themes. The recording quality was limited by the technical constraints of early PRC studios, but the emotional power of the performances came through clearly. The musical numbers were carefully integrated into the narrative, advancing both plot and character development.

Famous Quotes

"I am the White-Haired Girl! I have suffered in the dark mountains, but now I see the light of revolution!"

"The old society turns people into ghosts, the new society turns ghosts back into people!"

"Father, don't sell me! I would rather die than be separated from you!"

"The snow may cover the mountains, but it cannot extinguish the fire in my heart!"

"In the darkness of feudal oppression, even the purest snow becomes red with blood!"

Memorable Scenes

- The heartbreaking New Year's Eve scene where Yang Bailao is forced to sell his daughter, contrasting family warmth with cruel reality

- Xi'er's dramatic escape into the mountains during a thunderstorm, symbolizing her break from oppression

- The transformation scene where Xi'er discovers her hair has turned white from years of suffering and isolation

- The emotional reunion scene when Communist guerrillas discover the white-haired girl in the mountains

- The final liberation sequence where peasants rise up against the landlord system with Xi'er as their symbol

Did You Know?

- The film was one of the first major feature productions of the newly established People's Republic of China (founded in 1949)

- The original opera version was created in 1945 by the Lu Xun Academy of Arts in Yan'an

- Actress Tian Hua's performance as Xi'er became iconic and was used as a model for revolutionary art

- The film was shown extensively in rural areas as part of political education campaigns

- The white hair transformation was achieved through makeup techniques that were innovative for Chinese cinema at the time

- The story was based on multiple real cases of peasant oppression in pre-revolutionary China

- The film was later adapted into a ballet that became famous internationally

- Director Wang Bin was one of the pioneering filmmakers of early PRC cinema

- The film's success led to multiple remakes and adaptations over the decades

- The character of Xi'er became a symbol of the oppressed Chinese woman seeking liberation

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its powerful emotional impact and faithful adaptation of the revolutionary opera. Chinese film journals hailed it as a masterpiece of socialist art, praising its ideological clarity and artistic merit. International critics at film festivals noted its passionate storytelling and effective use of melodrama. Later film historians have recognized it as a landmark work that successfully bridged traditional Chinese storytelling with revolutionary themes. Some modern critics have noted its propagandistic elements but acknowledge its historical importance and artistic achievements within its political context.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with Chinese audiences, particularly in rural areas where its story of oppression and liberation resonated deeply. Many viewers reportedly wept during screenings, and Xi'er became a beloved figure representing the suffering and eventual triumph of the common people. The film was shown extensively in mobile cinema units that traveled to remote villages, making it one of the most-watched films of its era. Audience response was so strong that the film's songs and dialogue entered everyday conversation. The emotional connection viewers formed with the characters helped reinforce the film's political message about the necessity of social revolution.

Awards & Recognition

- Special Prize at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival (1951)

- Outstanding Film Award from the Chinese Ministry of Culture (1951)

- People's Film Award (1952)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet socialist realist cinema

- Traditional Chinese opera

- Chinese folk tales

- May Fourth Movement literature

- Yan'an revolutionary art traditions

This Film Influenced

- The Red Detachment of Women (1961)

- The Legend of the Red Lantern (1970)

- Spring in a Small Town (remake elements)

- The Story of Qiu Ju (thematic echoes)

- To Live (historical context)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the China Film Archive and has undergone digital restoration. Original nitrate elements were successfully transferred to safety stock in the 1970s. A restored version was released in 2008 as part of China's classic film preservation project. The film remains accessible through Chinese cultural institutions and has been screened at various international film festivals as part of Chinese cinema retrospectives.