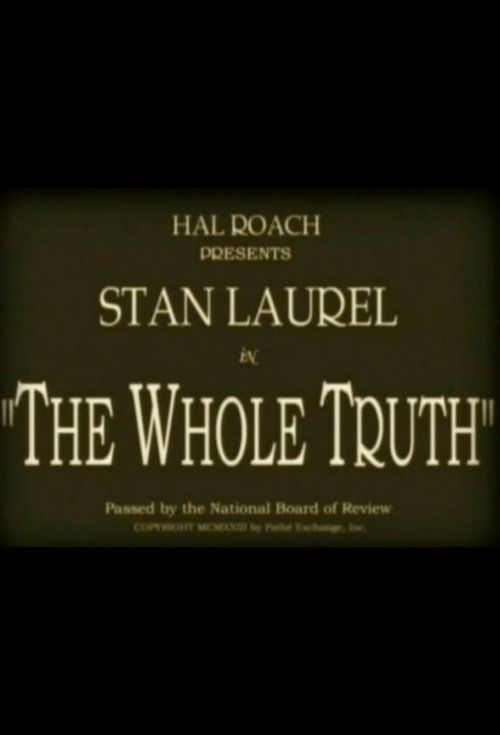

The Whole Truth

Plot

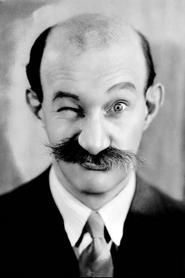

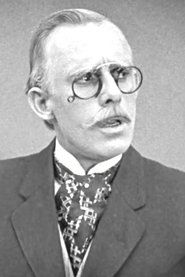

In this silent comedy short, a courtroom drama unfolds as a prosecutor presents a tearful, hysterical wife (Helen Gilmore) as a witness, claiming her emotional state is caused by her husband's frequent absences. The defense attorney (James Finlayson) represents the husband, who proudly admits to never doing anything worth being proud of. As the smirking defendant sips water in court, he becomes distracted and accidentally picks up the wrong glass, leading to comedic chaos when he consumes its unexpected contents. The film builds to a hilarious climax as the courtroom descends into pandemonium following the mistaken drink incident.

About the Production

This film was produced during Stan Laurel's early solo period at Hal Roach Studios, before his iconic partnership with Oliver Hardy was established. The film was shot on a modest budget typical of comedy shorts of the era, utilizing simple courtroom sets. The production team made use of practical effects for the mistaken drink sequence, likely using colored water or another harmless substance to create the visual gag.

Historical Background

The Whole Truth was produced in 1923, during the golden age of silent comedy in Hollywood. This era saw the rise of comedy as a dominant film genre, with studios like Hal Roach Productions competing with larger studios like Mack Sennett's Keystone and Charlie Chaplin's independent productions. The film industry was transitioning from short one-reelers to longer multi-reel features, though comedy shorts remained popular. 1923 was also a year of significant technological advancement in cinema, with improvements in film stock and camera equipment allowing for more sophisticated visual storytelling. The post-World War I economic boom was supporting a thriving entertainment industry, and movie theaters were becoming central to American social life. This period also saw the establishment of many comedic tropes and techniques that would influence comedy for decades to come.

Why This Film Matters

While 'The Whole Truth' may not be as well-known as some of its contemporaries, it represents an important transitional work in American comedy history. The film showcases the early development of physical comedy techniques that would become staples of the genre. It demonstrates the courtroom comedy format that would later be perfected in films like the Marx Brothers' 'Duck Soup' and later television shows. The collaboration between Laurel and Finlayson in this early work foreshadowed their future comedic chemistry in Laurel and Hardy films. The film also reflects the societal fascination with legal proceedings and the justice system during the 1920s, a theme that would continue to resonate throughout American popular culture. As a product of the Hal Roach Studios, it contributed to the studio's reputation for quality comedy that would eventually rival even Chaplin's productions.

Making Of

The production of 'The Whole Truth' took place during a formative period in comedy cinema at Hal Roach Studios. Stan Laurel was still developing his comic persona and had not yet created the character that would make him world-famous. The film was shot quickly on existing courtroom sets that the studio maintained for frequent use in various productions. Director Ralph Ceder, who had a keen eye for physical comedy, worked closely with the actors to perfect the timing of the gags, particularly the pivotal mistaken drink sequence. The cast rehearsed the physical comedy extensively, as silent films relied heavily on visual storytelling and precise timing. The film's simple premise allowed for improvisation within the structured courtroom setting, a technique Hal Roach encouraged to capture authentic comedic moments.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'The Whole Truth' was typical of comedy shorts of the era, utilizing static camera positions for most scenes to clearly capture the physical comedy and facial expressions of the actors. The camera work was functional rather than artistic, focusing on ensuring the gags were visible and well-framed. The courtroom setting allowed for simple, effective staging with the camera positioned to capture both the witness stand and the defendant's reactions. Lighting was flat and even, standard for comedy productions of the time, ensuring all expressions were clearly visible. The film likely used standard 35mm film stock common to Hal Roach productions of this period.

Innovations

While 'The Whole Truth' was not groundbreaking in its technical aspects, it demonstrated solid filmmaking craft typical of quality Hal Roach productions. The film made effective use of continuity editing to maintain the comedic timing across shots. The practical effects for the mistaken drink sequence, while simple, were executed effectively to create the desired comic impact. The film's pacing was well-controlled, building tension and releasing it at appropriate comedic moments. The use of intertitles was minimal and effective, allowing the visual comedy to carry most of the storytelling. The film represents the refinement of comedy film techniques that had been developing throughout the 1910s and early 1920s.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Whole Truth' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have included popular songs of the era, classical pieces, and specially composed cues to match the on-screen action. The courtroom scenes might have been accompanied by dramatic or suspenseful music, while the comedic moments would have featured lighter, more playful melodies. The mistaken drink sequence would likely have been scored with frantic, comedic music to enhance the humor. No original score survives, as was common with silent films, though modern screenings often use appropriate period music or newly composed scores.

Famous Quotes

Prosecutor: Observe the witness, ladies and gentlemen of the jury - a woman driven to tears by her husband's neglect!

Defense Attorney: My client has never done anything to be proud of - and he's proud of it!

Memorable Scenes

- The pivotal mistaken drink sequence where James Finlayson's character accidentally consumes the wrong liquid in court, leading to chaotic reactions and courtroom pandemonium

Did You Know?

- This was one of Stan Laurel's early solo shorts before his legendary partnership with Oliver Hardy began in 1927

- James Finlayson would later become a regular antagonist in Laurel and Hardy films, famous for his exasperated expressions and catchphrase 'D'oh!'

- The film was released during the peak of silent comedy production, when shorts were the standard format for comedy films

- Director Ralph Ceder was a prolific director of comedy shorts during the 1920s, working frequently with Hal Roach Studios

- Helen Gilmore was a character actress who appeared in over 200 films between 1915 and 1940, often playing mothers or elderly women

- The mistaken drink gag became a recurring trope in silent comedy, used by many comedians of the era

- The film was shot in just a few days, typical of the rapid production schedule for comedy shorts of this period

- Earl Mohan, another cast member, was a frequent collaborator with Laurel in his early solo work

- The courtroom setting was a popular backdrop for comedy shorts, allowing for structured chaos and visual gags

- This film is now considered part of the important transitional period in American comedy cinema

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of 'The Whole Truth' were generally positive, with trade publications noting the effective use of the courtroom setting for comedy and the strong performances by the cast. The Motion Picture News praised the film's 'clever gags and excellent timing,' while Variety noted that 'the mistaken drink sequence provides ample laughter.' Modern critics and film historians view the film as an interesting artifact of early Laurel work, showing his developing comedic style before his partnership with Hardy. The film is often cited in studies of silent comedy as an example of the effective use of confined spaces for comedic effect. While not considered a masterpiece of the era, it's regarded as a solid representative of the quality comedy shorts being produced by Hal Roach Studios during this period.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1923 responded positively to 'The Whole Truth,' as it contained the elements they expected from successful comedy shorts of the era: relatable situations, physical comedy, and a satisfying comedic resolution. The film played well in theaters as part of comedy programs, often paired with feature films or other shorts. Modern audiences who have seen the film, primarily through silent film festivals and archives, generally appreciate it as a charming example of early 1920s comedy, though it lacks the sophistication of later Laurel and Hardy works. The film's straightforward humor and visual gags remain accessible to contemporary viewers, making it a popular selection for silent comedy retrospectives.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Mack Sennett comedies

- Charlie Chaplin's early shorts

- Harold Lloyd's comedy style

This Film Influenced

- Later Laurel and Hardy courtroom comedies

- Marx Brothers' legal comedies

- Three Stooges courtroom shorts

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is believed to be preserved in various film archives, including the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. While not as widely circulated as some Laurel and Hardy films, prints exist in 16mm and 35mm formats. Some restoration work may have been done as part of broader silent film preservation efforts, but the film has not received a major standalone restoration project.