The Wrath of the Gods

"A Tale of Love and Faith in the Land of the Rising Sun"

Plot

An American sailor named Jack (Frank Borzage) arrives in a Japanese fishing village and falls in love with Toya San (Tsuru Aoki), the daughter of a devout fisherman (Sessue Hayakawa) who believes his daughter is cursed by the gods. Jack attempts to convert the family to Christianity, arguing that Jesus is more powerful than their traditional deities, creating tension between Western and Eastern spiritual beliefs. When a nearby volcano erupts and threatens to destroy the village, the characters' faiths are tested as they face the natural disaster together. The film culminates in a dramatic confrontation between traditional Japanese spirituality and Christian faith, with the volcanic eruption serving as both literal and metaphorical divine intervention that challenges everyone's beliefs about the true nature of divine power.

About the Production

The film was produced as part of Thomas H. Ince's prestigious production unit at Inceville, one of Hollywood's first major studio complexes. The volcanic eruption sequence was created using innovative special effects for 1914, including miniature models, controlled fires, smoke machines, and multiple camera angles. The production employed Japanese-American consultants and actors to achieve cultural authenticity, though the narrative was still filtered through a Western perspective. The elaborate Japanese village set was constructed on the Inceville backlot, complete with authentic props and architecture. The film was shot during the height of the 'Japonisme' craze in America, capitalizing on Western fascination with Japanese culture following Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a pivotal year in world history - 1914 marked the beginning of World War I in Europe, though America would remain neutral until 1917. In cinema, 1914 represented the transition from short films to feature-length productions in America, with audiences developing an appetite for longer, more complex narratives. The film emerged during the peak of 'Japonisme' in Western culture, a fascination with Japanese art and aesthetics that began in the late 19th century following Japan's opening to the West. This period also saw increased Asian immigration to the United States, particularly from Japan, leading to both fascination and xenophobia in American society. The film's religious themes reflected the active missionary movements of the Progressive Era, when many American churches sent missionaries to Asia. The early 1910s also witnessed the rise of the studio system, with producers like Thomas H. Ince pioneering methods of efficient, assembly-line film production that would dominate Hollywood for decades.

Why This Film Matters

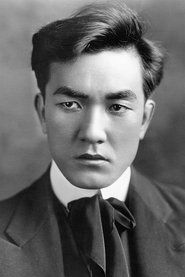

The Wrath of the Gods represents an important milestone in Asian-American representation in Hollywood, featuring Sessue Hayakawa in a leading role during a period when most Asian characters were played by white actors in yellowface. The film reflects the complex and often contradictory American attitudes toward Asian cultures in the early 20th century, combining genuine fascination with paternalistic assumptions about Western cultural superiority. Its exploration of religious conversion and cultural assimilation speaks to broader American anxieties about immigration and national identity during the Progressive Era. The film also demonstrates early Hollywood's ambitions to tell international stories, even when filtered through American sensibilities and moral frameworks. Hayakawa's stardom in this film and others challenged racial barriers in American cinema, though he was often typecast in exotic or villainous roles. The film's preservation status as partially lost also highlights the broader issue of film heritage and the loss of early cinema featuring minority performers.

Making Of

The production took place at Inceville, Thomas H. Ince's revolutionary studio complex in the Santa Monica Mountains, which was one of the first modern film studios. The elaborate Japanese village set was constructed with attention to architectural detail, incorporating authentic Japanese props and design elements. Sessue Hayakawa, already gaining fame from his breakthrough role in 'The Typhoon' (1914), brought significant star power to the production and likely had input into cultural aspects of the film. The volcanic eruption sequence required weeks of preparation and coordination between multiple departments, using techniques that were cutting-edge for 1914. The film's themes reflected real contemporary tensions between traditional Japanese culture and Western influence during the Meiji period. The collaboration between Japanese-American performers and Hollywood filmmakers was relatively progressive for its time, though the narrative still ultimately favored Western religious perspectives. The production schedule was tight, as was typical for Ince's efficient studio system, with the entire film completed in just a few weeks.

Visual Style

The film's cinematography, executed by Joseph H. August and other uncredited cameramen from Ince's regular crew, showcased the techniques common to the transitional period between early cinema and classical Hollywood style. The volcanic eruption sequence employed multiple camera angles and dynamic movement that was innovative for 1914, creating a sense of chaos and danger that enhanced the spectacle. The cinematography effectively balanced intimate character moments with grand set pieces, a hallmark of Thomas H. Ince's production philosophy. The lighting techniques, particularly in the dramatic religious and romantic scenes, used chiaroscuro effects to create emotional depth and visual interest. The film made effective use of the Inceville location, combining natural California landscapes with elaborate studio sets to create a convincing Japanese environment. The camera work during the action sequences demonstrated growing sophistication in motion picture photography, with smooth pans and tracking shots that added to the film's visual appeal.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was its volcanic eruption sequence, which combined multiple special effects techniques including miniature models, controlled fires, smoke machines, and innovative editing to create a convincing disaster sequence. The production utilized the then-cutting-edge technique of cross-cutting between different storylines and locations to build tension and create dramatic irony. The film's set design at Inceville included elaborate recreations of Japanese architecture, demonstrating the studio's growing capabilities in large-scale production design. The use of location shooting combined with studio work showed the increasing sophistication of film production methods in the early 1910s. The film also employed early forms of color tinting, particularly using amber and red tones for the fire scenes, which was common in prestige productions of the era to enhance mood and visual interest. The underwater sequences, though brief, demonstrated advances in underwater photography techniques that were still in their infancy.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Wrath of the Gods' would have been accompanied by live musical performances in theaters, with scores varying by venue size and resources. Large picture palaces would have employed full orchestras playing arrangements of classical pieces alongside original compositions, while smaller theaters might have had only a pianist or organist. The Japanese setting would have inspired the use of exotic-sounding music, possibly incorporating pentatonic scales or Japanese-inspired themes that were popular in Western classical music during this period. The volcanic eruption scenes would have been accompanied by dramatic, thunderous music using percussion and brass to enhance the spectacle and danger. Romantic moments between the leads would have featured lush, melodic themes, while religious scenes might have included hymn-like melodies or solemn organ music. The musical accompaniment was crucial in conveying emotion and narrative flow in the absence of dialogue, with skilled musicians improvising to match the on-screen action and emotional tone.

Famous Quotes

The gods of my ancestors are angry, but the God you speak of is more powerful than any mountain's fire.

Love knows no country, no race, no religion - it only knows the heart.

When the mountain speaks fire, all must listen - gods and men alike tremble before its wrath.

In the shadow of the volcano, we are all children of the same earth, seeking the same light.

Your Jesus may be powerful in your country, but here the old gods still rule the sea and sky.

Memorable Scenes

- The spectacular volcanic eruption sequence that threatens the entire village, combining impressive special effects with high emotional stakes as characters face their mortality and question their deepest beliefs about divine power and salvation.

Did You Know?

- Sessue Hayakawa and Tsuru Aoki were married in real life, having wed in 1914, the same year this film was released

- This was one of the earliest American films to feature Asian actors in leading roles rather than white actors in yellowface

- The film was part of a wave of 'Japonisme' in early Hollywood, with over 20 Japanese-themed films produced between 1910-1915

- Director Reginald Barker was one of Thomas H. Ince's most trusted protégés and would go on to direct over 100 films

- Frank Borzage, who plays the American sailor, would later win the first Academy Award for Best Director for '7th Heaven' (1927)

- The volcanic eruption effects were so impressive they were mentioned specifically in contemporary reviews as a highlight of the film

- The film was one of the first to directly address religious conversion and cultural assimilation themes in American cinema

- Thomas H. Ince, the uncredited producer, was known as the 'Father of the Western' but diversified into various genres including this Japanese drama

- The film's title refers to both the literal volcanic eruption and the metaphorical wrath of traditional Japanese deities

- Only fragments of this film are known to survive today, making it a partially lost film from the silent era

- The production coincided with the rise of feature-length films in America, marking the transition away from one-reel shorts

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in trade publications like The Moving Picture World and Variety praised the film's technical achievements, particularly the spectacular volcanic eruption sequence which was described as 'thrilling' and 'masterfully executed.' Critics noted Sessue Hayakawa's powerful screen presence and the film's ambitious scope in tackling themes of cultural and religious conflict. The New York Dramatic Mirror commented favorably on the film's moral message and impressive production values. Modern film historians view the film as an important artifact of early Asian representation in American cinema, though they critique its colonialist undertones and Western-centered perspective on Japanese spirituality. The film is frequently cited in scholarly works about Sessue Hayakawa's career and the broader patterns of racial representation in silent film. While some contemporary critics found the religious conversion elements heavy-handed, most acknowledged the film's entertainment value and technical merits.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1914 responded enthusiastically to the film's blend of romance, spectacle, and moral drama. The volcanic eruption scenes were particularly popular with viewers who were still experiencing the novelty of cinematic special effects, often drawing gasps and applause in theaters. The cross-cultural romance between the American sailor and Japanese woman resonated with contemporary audiences' taste for exotic love stories. The film's religious themes aligned with the moral sensibilities of many American moviegoers of the period, particularly those influenced by the Protestant missionary movement. However, some Japanese-American audience members likely found the portrayal of their culture stereotypical, though such perspectives were rarely documented in mainstream press of the era. The film's success contributed to Sessue Hayakawa's growing popularity and helped establish him as one of the first Asian-American movie stars.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Typhoon (1914) - another Hayakawa film exploring similar themes

- D.W. Griffith's films with cross-cultural themes

- Contemporary missionary literature and conversion narratives

- Popular novels about East-West encounters

- Stage melodramas with exotic settings

This Film Influenced

- Later films featuring Asian-American leads in mainstream cinema

- Disaster films of the silent era

- Cross-cultural romance narratives in Hollywood

- Films dealing with religious conversion and cultural assimilation

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is considered partially lost, with only fragments and possibly one incomplete reel known to survive in film archives. This makes it one of the many casualties of film preservation challenges from the silent era, when an estimated 75-90% of silent films have been lost due to neglect, decay, or destruction. Some still photographs, promotional materials, and written reviews survive, providing valuable documentation of the film's content and production. Surviving fragments may be held by archives such as the Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art's film department, or specialized silent film collections.