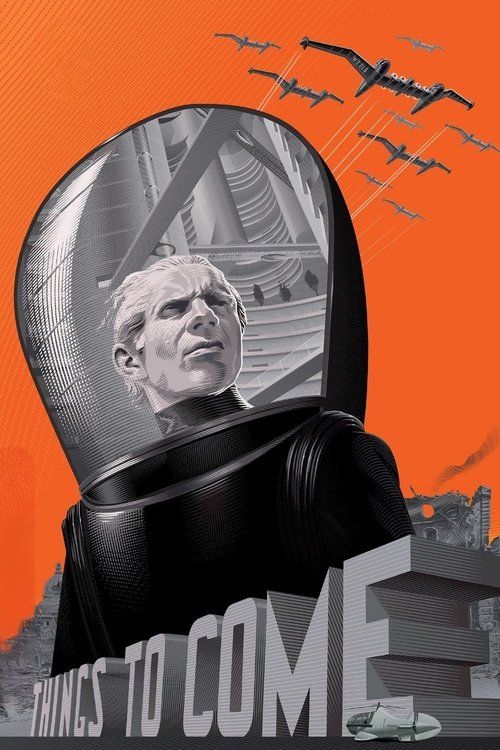

Things to Come

"The picture that will live forever!"

Plot

Things to Come spans nearly a century of human history, beginning in 1940 in the fictional English town of Everytown. When a devastating second World War breaks out and lasts for decades, civilization collapses into plague-ridden anarchy ruled by warlords. In 1970, the progressive technocrat John Cabal emerges to establish a new world order called Wings Over the World, which rebuilds civilization through scientific rationalism and collective planning. By 2036, this utopian society faces internal conflict as some citizens question the relentless pursuit of progress, culminating in a dramatic debate about humanity's future as the first space rocket prepares for launch to the Moon.

About the Production

The production was notably ambitious for its time, featuring elaborate miniature models and special effects that took nearly two years to complete. H.G. Wells himself was heavily involved in the production, writing the screenplay and insisting on specific artistic choices. The film's production was so complex that it required multiple units working simultaneously, with William Cameron Menzies supervising the overall visual design while other directors handled specific sequences.

Historical Background

Things to Come was produced during a period of intense political tension in Europe, with the rise of fascism in Germany and Italy, and the looming threat of another world war. The film's creation was deeply influenced by H.G. Wells' concerns about the direction of modern society and his belief in scientific rationalism as humanity's salvation. Made in 1936, when rearmament was beginning across Europe but before the full horrors of WWII became apparent, the film served as both warning and prophecy. Its release coincided with the Spanish Civil War and the remilitarization of the Rhineland, events that seemed to validate Wells' pessimistic predictions about imminent global conflict. The film's emphasis on collective planning and international cooperation reflected contemporary debates about how to prevent another world war, while its celebration of technological progress mirrored the modernist optimism of the 1930s, even as dark clouds gathered over Europe.

Why This Film Matters

Things to Come represents a landmark in science fiction cinema, establishing many conventions and visual motifs that would define the genre for decades. It was one of the first major science fiction films to deal with serious philosophical themes rather than simple adventure, treating science fiction as a vehicle for social commentary and intellectual debate. The film's elaborate production design and special effects set new standards for what was possible in cinema, influencing countless subsequent films from Metropolis to 2001: A Space Odyssey. Its portrayal of a future shaped by scientific progress and humanistic values reflected and shaped popular attitudes about technology's role in society. The film's structure, spanning decades of future history, pioneered the epic science fiction narrative form later seen in films like 2001 and Blade Runner. Its influence extended beyond cinema to literature, television, and even architectural design, with its vision of the future city inspiring real-world urban planning discussions.

Making Of

The production of Things to Come was marked by intense collaboration and conflict between H.G. Wells and the filmmakers. Wells, then 70 years old, was determined to see his vision realized exactly as he imagined it, spending long hours on set and often rewriting scenes during filming. Director William Cameron Menzies, though officially credited as production designer, effectively co-directed the film alongside several uncredited directors. The special effects team, led by Lawrence Butler, pioneered numerous techniques including traveling mattes and miniature photography that would become industry standards. The casting was particularly significant - Raymond Massey was Wells' personal choice for the lead, believing his stern, intellectual presence perfectly embodied the rationalist hero. The war sequences were filmed using innovative techniques, including actual explosions and miniature models that were photographed at high speed to create realistic destruction. The production faced numerous delays due to the complexity of the effects work, with the futuristic city models requiring months of construction and testing.

Visual Style

The cinematography, primarily by Georges Périnal, was revolutionary for its time, employing innovative techniques to create the film's visionary future worlds. The use of deep focus photography allowed for complex compositions showing both foreground and background elements in sharp detail, particularly effective in the futuristic city sequences. The film pioneered the use of traveling mattes to combine live action with miniature models, creating seamless integration between actors and elaborate sets. The war sequences utilized handheld cameras and rapid editing to create documentary-like realism, while the future scenes employed smooth, gliding camera movements to convey technological advancement. The lighting design evolved dramatically throughout the film, from the harsh, naturalistic light of the war years to the clean, artificial illumination of the future society. The black and white photography was used to maximum effect, with strong contrasts between the darkness of the war years and the brightness of the technological future.

Innovations

Things to Come was groundbreaking in numerous technical aspects, setting new standards for special effects and production design. The film's miniature effects, supervised by Lawrence Butler, were revolutionary, using forced perspective and innovative camera techniques to create convincing cityscapes and destruction sequences. The development of the traveling matte process allowed for seamless integration of actors with miniature sets, a technique that would become standard in the industry. The film featured some of the earliest uses of process projection for background elements, particularly in the flying sequences. The production design by William Cameron Menzies introduced the concept of 'production designer' as a distinct creative role, with his comprehensive visual approach influencing how films would be designed thereafter. The film's sound recording techniques were also advanced for the time, using multiple microphones and innovative mixing to create complex audio environments. The space launch sequence used revolutionary optical printing techniques to create the illusion of rocket propulsion and space travel.

Music

The musical score was composed by Arthur Bliss, one of Britain's leading classical composers, who created what is considered one of the first truly modern film scores. Rather than using traditional romantic themes, Bliss employed dissonant harmonies and rhythmic complexity to reflect the film's modernist themes. The score was notable for its use of leitmotifs to represent different concepts and characters, with the 'Wings Over the World' theme becoming particularly iconic. Bliss incorporated electronic elements, including the theremin, to create otherworldly sounds for the space sequences. The music was recorded by a full orchestra at EMI's Abbey Road Studios, making it one of the most ambitious film scores of its time. The soundtrack also featured innovative sound design, with the mechanical sounds of the future city created using industrial recordings and manipulated audio. The complete score was later released as a concert suite and remains one of the most celebrated film compositions of the 1930s.

Famous Quotes

'Which shall it be? Progress or chaos?' - John Cabal

'We have learned. We have learned that the individual is nothing, the species is everything.' - Oswald Cabal

'For Man is nothing... but... what he makes of himself!' - Oswald Cabal

'All the universe or nothingness. Which shall it be, Passworthy? Which shall it be?' - Oswald Cabal

'If we don't end war, war will end us.' - John Cabal

'The old world is dying. A new world is struggling to be born.' - The Boss

'In all the universe, nothing remains constant. Nothing.' - Oswald Cabal

'We're not going to be afraid anymore. We're going to be masters!' - John Cabal

Memorable Scenes

- The opening Christmas Eve sequence where the threat of war looms over festive celebrations, creating a powerful juxtaposition of peace and impending doom

- The devastating air raid on Everytown, featuring groundbreaking special effects of bombing and destruction that proved eerily prophetic

- The emergence of John Cabal in his flying machine, representing the dawn of a new technological age

- The reveal of the futuristic city of 2036, with its sweeping architecture and advanced technology

- The climactic space launch sequence, where humanity reaches for the stars despite internal conflict

- The confrontation between The Boss and John Cabal, representing the clash between barbarism and civilization

- The final debate aboard the space gun about humanity's future, encapsulating the film's central philosophical themes

Did You Know?

- H.G. Wells was so determined to maintain creative control that he insisted on final cut privileges and personally oversaw every aspect of production, making this one of the few films where a major author had such complete authority over the adaptation of their work.

- The film's massive scale required over 3,000 extras, many of whom were actual British soldiers on leave during the war sequences.

- The futuristic city models were so detailed and expensive that they cost more than the entire budgets of many contemporary British films.

- Raymond Massey played both John Cabal and his grandson Oswald Cabal, becoming one of the first actors to play dual roles in a science fiction film to show generational progression.

- The film predicted many technological advances that eventually came true, including video phones, television screens in public spaces, and international air travel.

- The bombing sequences were so realistic that they were reportedly used as actual training footage by the British military during WWII.

- The original running time was 130 minutes, but Wells himself supervised cuts to bring it down to a more manageable length for theatrical release.

- The film's title was changed from 'The Shape of Things to Come' to simply 'Things to Come' for its American release to avoid confusion with Wells' novel.

- The famous 'space gun' sequence took six months to film using revolutionary special effects techniques.

- Despite being made in 1936, the film's depiction of gas masks and air raid precautions proved eerily prescient when WWII began three years later.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was mixed but generally respectful of the film's ambitions. The Times of London praised its 'bold conception and magnificent execution' while noting that Wells' 'didactic purpose sometimes overwhelms the dramatic interest.' American critics were more enthusiastic, with The New York Times calling it 'the most ambitious and thought-provoking science fiction film yet produced.' Over time, critical appreciation has grown significantly, with modern critics recognizing it as a masterpiece of science fiction cinema. Film historian David Shipman called it 'the most important British science fiction film ever made,' while Sight & Sound magazine included it in their list of the greatest films of all time. Contemporary critics particularly praise its visionary production design, its intellectual ambition, and its prescient predictions about future technology and society.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception was somewhat disappointing, particularly in Britain where the film's intellectual tone and didactic elements failed to connect with mainstream moviegoers accustomed to more conventional entertainment. Many found Wells' philosophical speeches heavy-handed and the pacing too slow. However, the film developed a cult following among intellectuals and science fiction enthusiasts who appreciated its serious approach to speculative themes. American audiences were somewhat more receptive, though the film still performed modestly at the box office. Over the decades, audience appreciation has grown substantially, with the film now regarded as a classic by science fiction fans and cinema enthusiasts. Modern audiences often express surprise at how many of the film's predictions about technology and society proved accurate, as well as its relevance to contemporary debates about progress, technology, and human values.

Awards & Recognition

- National Board of Review Award for Best Foreign Film (1936)

- Venice Film Festival - Mussolini Cup nomination (1936)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Metropolis (1927)

- Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

- The Shape of Things to Come by H.G. Wells

- Soviet constructivist art and architecture

- Bauhaus design principles

- Italian Futurism

- German Expressionist cinema

This Film Influenced

- 2001: A Space Odyssey

- Blade Runner

- Brazil

- Metropolis

- The Day the Earth Stood Still

- Planet of the Apes

- Star Wars

- Children of Men

- Gattaca

- The Matrix

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been well-preserved and restored multiple times. The British Film Institute holds original elements and has overseen several restorations, most notably for the 2013 Blu-ray release. The original nitrate negatives survived, allowing for high-quality digital restoration. Both the British and American versions exist in archives, with the British cut generally considered definitive. The film entered the public domain in many countries, which has led to numerous home video releases of varying quality. Criterion Collection released a specially restored version in 2013 with extensive bonus features. The restoration work has revealed details and visual effects not seen since the original theatrical release.