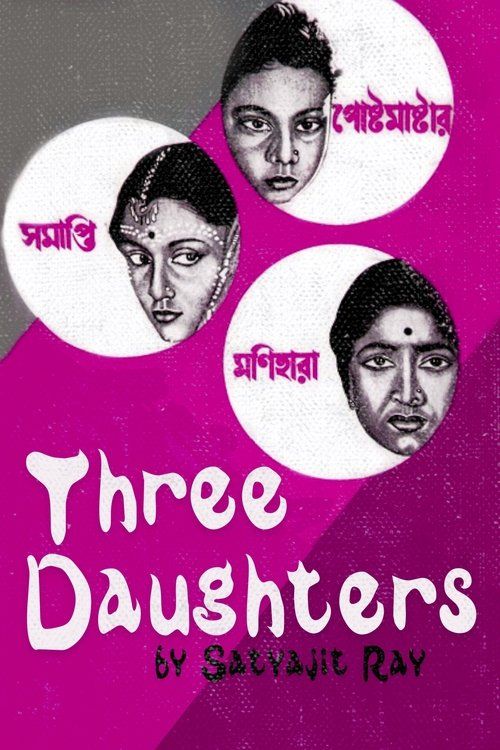

Three Daughters

"Three stories of three women, three different worlds of emotion and experience"

Plot

Satyajit Ray's 'Teen Kanya' (Three Daughters) is an anthology film comprising three distinct stories centered on female protagonists in rural Bengal. The first segment, 'The Postmaster,' follows Nandalal, a young city-bred postmaster who teaches his orphaned housemaid Ratan to read and write, forming an emotional bond that is tested when he must leave for his hometown. The second story, 'Monihara,' tells the supernatural tale of a wealthy woman Phuljhuri who becomes obsessed with her husband's jewelry purchases, leading to a tragic and ghostly revelation about the true cost of her materialism. The final segment, 'Samapti,' follows Amulya, a young man who returns to his village after completing his studies and falls for the spirited, unconventional Mrinmoyi instead of his arranged bride, the demure and proper daughter of a respectable family. Each story explores different aspects of women's lives, desires, and circumstances in early 20th century Bengal, connected by Ray's sensitive portrayal of female psychology and social constraints.

About the Production

The film was adapted from three short stories by Rabindranath Tagore: 'Postmaster' and 'Samapti' were directly adapted, while 'Monihara' was loosely based on Tagore's 'Monihara.' Ray made significant changes to the source material, particularly in 'Monihara,' where he added supernatural elements not present in the original story. The film was shot in black and white by cinematographer Subrata Mitra, who continued his pioneering work with natural lighting techniques. Ray faced challenges in finding suitable locations that matched the period setting of Tagore's stories and worked extensively with his art director to create authentic rural Bengal environments.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a significant period in Indian cinema history when parallel cinema was gaining recognition internationally. 1961 marked the centenary of Rabindranath Tagore's birth, and there was renewed interest in adapting his works for modern audiences. Post-independence India was experiencing cultural renaissance, with filmmakers like Ray helping establish Indian cinema's artistic credentials on the world stage. The early 1960s also saw the emergence of the Indian New Wave movement, with 'Teen Kanya' representing the bridge between Ray's earlier neorealist works and his more psychologically complex later films. The film's exploration of women's roles in traditional Bengali society reflected ongoing social debates about women's education, marriage practices, and autonomy in post-colonial India.

Why This Film Matters

'Teen Kanya' holds a unique place in cinema history as one of the earliest and most successful anthology films in Indian cinema. Ray's adaptation of Tagore's works helped introduce international audiences to Bengali literature and culture while preserving the essence of Tagore's feminist sensibilities. The film's three female protagonists represented different aspects of women's struggles and desires in traditional society, making it a pioneering work in feminist cinema from India. The film's international success, particularly in Europe and America, helped establish the legitimacy of Indian art cinema and inspired a generation of Indian filmmakers to explore literary adaptations. Ray's sensitive portrayal of rural Bengal and his nuanced understanding of female psychology influenced how Indian women were represented in serious cinema, moving away from stereotypical portrayals toward more complex, realistic characterizations.

Making Of

Satyajit Ray approached 'Teen Kanya' as a tribute to Rabindranath Tagore, whose works had profoundly influenced him since childhood. The production was particularly challenging as Ray was essentially making three short films simultaneously, each requiring different sets, costumes, and emotional tones. For 'The Postmaster,' Ray worked extensively with child actor Chandana Banerjee (Ratan), spending weeks helping her understand the character's emotional journey. The 'Monihara' segment required careful planning of the supernatural elements, with Ray using innovative camera techniques and lighting to create the ghostly atmosphere without resorting to obvious special effects. In 'Samapti,' Ray discovered Madhabi Mukherjee's talent during auditions and was so impressed that he rewrote certain scenes to better showcase her abilities. The film's music, composed by Ray himself, incorporated Tagore's songs, requiring extensive research into authentic Bengali folk and classical traditions. Ray's meticulous attention to extended to period details, with costumes and props carefully researched to match early 20th century Bengal accurately.

Visual Style

Subrata Mitra's cinematography in 'Teen Kanya' demonstrated his mastery of natural lighting techniques, which he had pioneered in Ray's earlier films. Each segment employed distinct visual approaches: 'The Postmaster' used soft, natural light to create an intimate, gentle atmosphere reflecting the emotional bond between the characters. 'Monihara' featured dramatic chiaroscuro effects and deep shadows to enhance the supernatural elements and psychological tension, with Mitra using innovative bounce lighting techniques to create eerie, ghostly atmospheres. 'Samapti' showcased vibrant outdoor photography capturing the lush Bengal countryside and the energy of village life. Mitra's use of deep focus and careful composition allowed Ray to frame multiple characters within single shots, emphasizing their relationships and social contexts. The black and white photography added emotional depth to each story, with Mitra's tonal variations helping distinguish the three segments while maintaining visual cohesion throughout the anthology.

Innovations

While not technically experimental in the same way as some of Ray's other works, 'Teen Kanya' showcased several notable technical achievements. The anthology format itself was innovative for Indian cinema, requiring Ray to maintain narrative and thematic coherence across three distinct stories. Subrata Mitra continued his pioneering work with natural lighting, particularly in the challenging indoor scenes of 'Monihara,' where he created supernatural effects through innovative lighting techniques rather than post-production manipulation. The film's editing, handled by Ray himself, demonstrated sophisticated transitions between segments while maintaining emotional continuity. The production design, led by Bansi Chandragupta, created authentic period settings for stories set in early 20th century Bengal, with meticulous attention to architectural details, costumes, and props. The film's sound recording, particularly in outdoor village scenes, captured the ambient sounds of rural Bengal with remarkable clarity, adding to the film's immersive quality.

Music

The film's music was composed by Satyajit Ray himself, drawing heavily from Rabindranath Tagore's extensive body of songs (Rabindra Sangeet). Ray carefully selected and adapted Tagore's compositions to enhance the emotional atmosphere of each segment while maintaining cultural authenticity. The soundtrack featured traditional Bengali instruments including the tabla, harmonium, and esraj, blended with Western orchestral elements to create a unique musical language that bridged traditional and modern sensibilities. For 'The Postmaster,' Ray used simple, melodic themes reflecting the innocence of the central relationship. 'Monihara' incorporated more dramatic, dissonant elements to underscore the supernatural and psychological tension. 'Samapti' featured lighter, more playful melodies matching the story's romantic and humorous elements. The film's sound design also emphasized natural ambient sounds of rural Bengal - birds, monsoon rains, village activities - creating an immersive audio environment that complemented the visual storytelling.

Famous Quotes

Ratan: 'Dada, will you teach me to read? I want to read your letters when they come.'

Postmaster: 'In this big world, we are all like orphans, Ratan. We must learn to stand alone.'

Phuljhuri: 'These jewels are not just gold and stones, they are my dreams, my life!'

Mrinmoyi: 'I am not a doll to be dressed up and married off. I have a mind, I have a will!'

Amulya: 'In her eyes, I see not just a girl, but the freedom I never knew I wanted.'

Narrator (Monihara): 'Sometimes the ghosts that haunt us are not the dead, but the living desires that consume us.'

Memorable Scenes

- The emotional farewell scene between the Postmaster and Ratan, where she silently hands him a handmade gift as he departs, capturing the pain of unspoken attachment and social separation

- The climactic scene in 'Monihara' where the ghostly apparition appears, revealing the supernatural consequences of material obsession through Ray's masterful use of shadow and suggestion rather than explicit effects

- The playful yet defiant scene where Mrinmoyi climbs a tree to escape her arranged marriage meeting, symbolizing her rejection of traditional constraints and assertion of independence

- The montage in 'The Postmaster' showing Ratan's progress in learning to write, with close-ups of her determined face forming letters in the dust, representing education as empowerment

- The final scene of 'Samapti' where Mrinmoyi and Amulya reconcile, suggesting that love can bridge the gap between tradition and individual desire

Did You Know?

- The film was originally released in India as 'Teen Kanya' but internationally distributed as 'Three Daughters,' though some markets used the title 'Three Girls'

- When first exported internationally, distributors often removed the middle segment 'Monihara,' releasing only 'The Postmaster' and 'Samapti' as a shorter film titled 'Two Daughters'

- Rabindranath Tagore, whose stories the film adapts, was a Nobel laureate and Ray had long wanted to bring his works to the screen

- The segment 'Monihara' was Ray's first attempt at a supernatural/ghost story genre

- Actress Madhabi Mukherjee, who starred in 'Samapti,' would later become Ray's muse and star in his masterpiece 'Charulata' (1964)

- The film's release coincided with Tagore's centenary birth celebrations in India

- Ray considered 'Teen Kanya' to be among his most personal works due to his deep admiration for Tagore

- The postmaster character was played by Anil Chatterjee, who had previously worked with Ray in 'Apur Sansar' (1959)

- The film's title sequence was designed by Ray himself, reflecting his background as a graphic artist

- Each segment was shot with slightly different visual approaches to reflect their distinct tones - 'The Postmaster' with gentle naturalism, 'Monihara' with dramatic shadows and lighting, and 'Samapti' with more vibrant outdoor sequences

What Critics Said

Upon its release, 'Teen Kanya' received widespread critical acclaim both in India and internationally. Indian critics praised Ray's faithful yet innovative adaptation of Tagore's works, with particular appreciation for his ability to capture the essence of Bengali rural life. International critics, including those at Cannes and The New York Times, lauded the film's humanistic approach and technical mastery. The segment 'The Postmaster' was especially praised for its emotional depth and subtle performances, while 'Monihara' was noted for its successful blend of supernatural elements with psychological realism. Over time, the film has come to be regarded as one of Ray's most important works, with film scholars highlighting its role in establishing the anthology format in Indian cinema and its sophisticated treatment of female perspectives. Modern critics continue to praise the film's timeless themes and Ray's masterful storytelling, considering it a landmark in world cinema.

What Audiences Thought

The film resonated strongly with Bengali audiences who appreciated Ray's respectful treatment of Tagore's beloved stories. The emotional connection viewers formed with the three female protagonists led to discussions about women's roles in traditional society, making the film not just entertainment but a catalyst for social dialogue. International audiences, particularly in art house cinemas, responded positively to the film's universal themes and accessible storytelling. Over the decades, the film has maintained its appeal through television broadcasts and film retrospectives, with new generations discovering its timeless qualities. The segment 'Samapti' became particularly popular for its humorous yet insightful portrayal of young love and rebellion against arranged marriage conventions. The film's reputation has grown over time, with many considering it one of Ray's most emotionally accessible works alongside his more formally ambitious films.

Awards & Recognition

- National Film Award for Best Feature Film in Bengali (1961)

- President's Silver Medal for Best Feature Film (1961)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Italian neorealism (particularly in 'The Postmaster' segment)

- Rabindranath Tagore's literary works

- Bengali folk storytelling traditions

- Japanese cinema's anthology format (inspired by works like 'Rashomon')

- French poetic realism (particularly in the visual style of 'Monihara')

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Indian anthology films including 'Kahani' and 'Bombay Talkies'

- Modern Bengali cinema's focus on female-centric narratives

- International art house films exploring women's lives in traditional societies

- Films adapting literary works into multi-segment formats

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been well-preserved through the efforts of the Satyajit Ray Society and various film archives. The Academy Film Archive has preserved 'Teen Kanya' as part of their Satyajit Ray collection. The Criterion Collection released a restored version as part of their Satyajit Ray box set, ensuring high-quality digital preservation. The original negatives are maintained at the National Film Archive of India. The film has undergone digital restoration several times, most recently in 4K resolution, making it accessible to modern audiences while preserving Ray's artistic vision.