Torn Boots

Plot

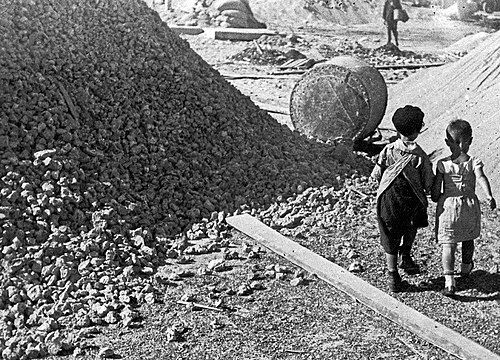

Torn Boots is a revolutionary Soviet drama that explores class struggle through the eyes of children living in a society that represents pre-Nazi Germany. The film follows a group of working-class children whose daily lives and games serve as a mirror to the absurd and oppressive adult world around them. Through their innocent yet perceptive interactions, the children reveal the contradictions and injustices of a capitalist society on the brink of fascism. The narrative weaves together their playful adventures with the serious social commentary, showing how the young protagonists navigate a world that simultaneously excludes them as both proletarians and minors. The film culminates in a powerful statement about resistance and the potential for revolutionary change, embodied by the children's natural inclination toward solidarity and justice.

About the Production

The film was notable for its innovative use of direct sound recording techniques, which was uncommon in Soviet cinema of the early 1930s. Director Margarita Barskaya worked closely with child actors, employing methods that prioritized natural behavior over staged performances. The production faced challenges from Soviet authorities due to its experimental style and ambiguous political messaging. The reconstruction of pre-Nazi German society was reportedly advised by Karl Radek, adding political depth to the visual design.

Historical Background

Torn Boots was created during a critical period in Soviet history, as the country was undergoing rapid industrialization and social transformation under Stalin's First Five-Year Plan. The early 1930s represented a brief window of artistic freedom in Soviet cinema before the imposition of Socialist Realism as the only approved artistic style in 1934. The film's depiction of pre-Nazi Germany was particularly prescient, as Hitler would rise to power in Germany the same year the film was released. This historical context gave the film an urgent political dimension, as it warned about the dangers of fascism while simultaneously critiquing capitalist society. The Soviet Union's position as the world's first socialist state made films like Torn Boots important tools for ideological education, though Barskaya's experimental approach pushed the boundaries of what was considered acceptable propaganda. The film's focus on class struggle through children's eyes reflected Soviet educational philosophy about raising the new socialist man from childhood.

Why This Film Matters

Torn Boots represents a significant but often overlooked contribution to the tradition of politically engaged children's cinema, standing alongside works like Jean Vigo's Zero for Conduct as a pioneering example of using childhood perspectives to critique adult society. The film's experimental style and anarchist spirit influenced subsequent generations of filmmakers interested in breaking cinematic conventions. Its preservation and championing by Henri Langlois helped establish its reputation in film history circles, particularly among critics and scholars interested in avant-garde cinema. The film serves as an important example of female directorship in early Soviet cinema, highlighting Margarita Barskaya's unique vision and approach to filmmaking. Its sophisticated use of children as social commentators prefigured later developments in world cinema, particularly the French New Wave's interest in childhood as a lens for social critique. The film's complex take on Western society and its subtle political commentary demonstrate the sophistication possible within Soviet cinema during this brief period of artistic freedom.

Making Of

Margarita Barskaya approached the making of Torn Boots with a unique methodology that prioritized the authentic voices and behaviors of children. She spent considerable time observing children in their natural environments, developing a shooting style that captured their spontaneity and unfiltered perspectives. The film's production was marked by Barskaya's insistence on using direct sound recording techniques, which allowed for the natural capture of children's voices and ambient sounds rather than relying on post-production dubbing. This technical choice was innovative for Soviet cinema of the period and contributed significantly to the film's documentary-like feel. The collaboration with Karl Radek for the depiction of German society added political sophistication to the production, though it also risked drawing unwanted attention from Soviet authorities. Barskaya's feminist perspective as a female director in a male-dominated industry informed the film's focus on marginalized voices, particularly those of children who were doubly excluded from power structures.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Torn Boots was revolutionary for its time, employing a dynamic and sometimes chaotic visual style that mirrored the energy and unpredictability of childhood. The camera work often utilized low angles to capture the world from children's perspectives, creating a sense of immediacy and identification with the young protagonists. The film featured extensive location shooting rather than relying solely on studio sets, contributing to its documentary-like authenticity. Visual compositions frequently emphasized the contrast between the small scale of children and the overwhelming adult world they inhabited. The cinematography incorporated elements of Soviet montage theory but subverted them through its focus on spontaneous action rather than carefully constructed sequences. The visual style was particularly effective in capturing the play sequences, using handheld camera techniques that followed children's movements with fluidity and grace.

Innovations

Torn Boots was technically innovative for its use of direct sound recording techniques, which allowed for more authentic capture of dialogue and ambient sounds than was common in Soviet cinema of the period. The film's approach to working with child actors represented a significant achievement in performance direction, prioritizing natural behavior over staged performances. The cinematography employed innovative techniques for capturing children's perspectives, including extensive use of low angles and mobile camera work. The film's editing style broke from conventional Soviet montage techniques, creating a more fluid and spontaneous rhythm that mirrored the unpredictability of childhood. The production design successfully created a convincing representation of pre-Nazi Germany while maintaining the film's Soviet perspective. The film's balance of political messaging with artistic experimentation represented an important technical and aesthetic achievement in early Soviet sound cinema.

Music

The film's soundtrack was notable for its innovative use of direct sound recording, which was relatively uncommon in Soviet cinema of the early 1930s. This technical choice allowed for the authentic capture of children's voices and ambient sounds from their environment, contributing to the film's documentary-like quality. The musical score likely incorporated elements of Soviet popular music and possibly revolutionary songs, though specific details about the composer and musical selections are not well-documented. The sound design emphasized the contrast between the natural sounds of children's play and the artificial noises of the adult world. The film's use of sound was integral to its political messaging, with children's voices often serving as a counterpoint to adult authority. The intertitles, while minimal, were strategically placed to reinforce the film's central themes about the relationship between play and life.

Famous Quotes

They play in the same way that they live

The games of children reveal the truth of society

In the eyes of children, we see the future we are creating

When children laugh, the powerful tremble

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing children playing in the streets, establishing the film's visual style and thematic focus

- The scene where children's games mirror adult political activities, demonstrating the film's complex social commentary

- The climactic sequence where the children's innocent rebellion takes on political significance

- The intertitle moments that bridge the gap between child's play and social reality

Did You Know?

- The film was nearly lost to history but was preserved and championed by French film archivist Henri Langlois, who was seduced by its rebellious spirit

- Director Margarita Barskaya was one of the few female directors working in the Soviet film industry during the 1930s

- The film's style was deliberately chaotic and anarchic, breaking away from conventional cinematic syntax of the era

- It has been frequently compared to Jean Vigo's 'Zero for Conduct' (1933) for its similar themes of childhood rebellion against adult authority

- The intertitle 'They play in the same way that they live' encapsulates the film's central philosophy about the relationship between children's games and social reality

- The film's depiction of pre-Nazi Germany was subtle enough to avoid censorship but clear enough for contemporary audiences to understand the reference

- Margarita Barskaya's work with children was considered revolutionary for its time, emphasizing authentic child performances rather than adult-directed acting

- The film was part of a brief period of artistic experimentation in Soviet cinema before Stalinist aesthetic policies became more rigid

- Despite its artistic merits, the film was not widely distributed internationally during its initial release

- The title 'Torn Boots' serves as a metaphor for the working-class condition and the worn state of the proletariat under capitalism

What Critics Said

Upon its initial release, Torn Boots received mixed reactions from Soviet critics, who appreciated its political message but were sometimes uncomfortable with its experimental style and lack of conventional narrative structure. Some critics praised Barskaya's innovative approach to working with child actors and her authentic capture of children's perspectives. Western critics, particularly those associated with avant-garde cinema circles, later championed the film for its rebellious spirit and formal innovations. Henri Langlois of the Cinémathèque Française was especially instrumental in bringing the film to international attention, describing it as seductive in its anarchy and love of children. Contemporary film historians have reevaluated the film as a significant work of early Soviet cinema, appreciating its complex political messaging and formal experimentation. The comparison to Jean Vigo's Zero for Conduct has become a standard reference point in discussions of the film, highlighting its place in the international tradition of radical children's cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception in the Soviet Union is difficult to document precisely, but the film's limited distribution and experimental nature likely meant it reached a relatively small audience compared to more conventional Soviet productions of the period. Among those who did see it, the film's portrayal of children's perspectives likely resonated with Soviet viewers who valued films about youth and education. The film's international audience grew significantly over time, particularly after its preservation and presentation by film archives like the Cinémathèque Française. Modern audiences encountering the film through retrospectives and film festivals have often been struck by its contemporary relevance and formal boldness. The film's appeal to cinephiles interested in rare and experimental works has helped maintain its reputation among specialized audiences, even as it remains largely unknown to general moviegoers.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet montage theory

- Jean Vigo's Zero for Conduct

- Documentary film techniques

- Political cinema traditions

- Children's literature and educational theory

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet children's films

- French New Wave films about childhood

- Political cinema using child protagonists

- Experimental documentaries

- Social realist films internationally

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered partially lost for many years but was preserved through the efforts of international film archives, particularly the Cinémathèque Française under Henri Langlois. While not all elements may be complete, enough of the film survives to represent Barskaya's vision and artistic achievements. The preservation status makes it a rare but accessible example of early Soviet experimental cinema for modern audiences.