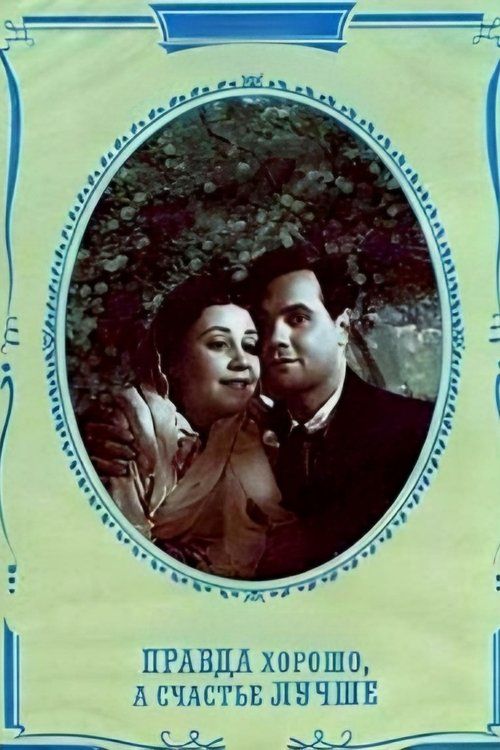

Truth is Good, But Happiness is Better

"In the game of love and social status, who really wins?"

Plot

The imperious matriarch Mavra Tarasovna, mother of wealthy Moscow merchant Amos Panfilovich Baraboshev, is determined to find a prestigious general as a husband for her beloved granddaughter Polyxena. Despite Polyxena's love for the modest clerk Glumov, Mavra Tarasovna dismisses him as unsuitable and pushes for a match with General Babarikin. The film follows the comedic complications that arise from this marriage arrangement, as Polyxena resists her grandmother's plans while the various suitors and family members navigate the complex social dynamics of 19th-century Russian merchant society. Through a series of misunderstandings, revelations, and social maneuvering, the story ultimately explores the conflict between social ambition and personal happiness, questioning whether truth and social status are truly more valuable than genuine contentment and love.

About the Production

This adaptation was filmed during the early post-World War II period when Soviet cinema was focused on creating films that reinforced traditional values while providing entertainment. The production faced the typical constraints of the Soviet film industry, including strict censorship guidelines and limited resources. The film was shot in black and white using standard Soviet camera equipment of the period, with careful attention to recreating the 19th-century merchant class setting described in Ostrovsky's original play.

Historical Background

This film was produced in 1951, during the final years of Stalin's rule and at the height of the Cold War. The Soviet Union was recovering from World War II's devastation, and the cultural policy known as the Zhdanov Doctrine was in full effect, demanding that all art serve socialist ideals. Despite these restrictive conditions, adaptations of classical Russian literature were often approved as they showcased Russia's cultural heritage. Ostrovsky's works, while critical of 19th-century Russian society, could be framed as exposing the evils of pre-revolutionary Russia, making them acceptable to Soviet authorities. The film's themes of social mobility and the conflict between traditional values and personal happiness resonated with post-war Soviet audiences who were experiencing significant social changes themselves.

Why This Film Matters

The film represents an important example of how Soviet cinema adapted classical Russian literature for contemporary audiences. While many literary adaptations of this era were heavily politicized, this production maintained much of Ostrovsky's original social satire and comedy. The film helped preserve and popularize Ostrovsky's work for new generations of Soviet viewers, contributing to the continued relevance of 19th-century Russian literature in Soviet culture. Its portrayal of merchant class life also served as a historical document, showing Soviet audiences the stark differences between pre-revolutionary Russian society and contemporary Soviet life. The film's success demonstrated that even under strict cultural policies, comedy and social commentary could find expression through classical adaptations.

Making Of

The production of 'Truth is Good, But Happiness is Better' took place during a challenging period in Soviet cinema history. Director Sergei Alekseyev, coming from a theatrical background, insisted on maintaining the play's comedic timing and social satire while working within the constraints of Soviet censorship. The cast, many of whom were experienced theater actors, had to adapt their stage performances for the camera, resulting in a style that blended theatrical and cinematic techniques. The film was shot at Gorky Film Studio, one of Moscow's largest production facilities, using available sets that were modified to recreate 19th-century Moscow. The production team faced particular challenges in balancing the play's satirical elements with the Soviet requirement that films present positive social values. Despite these constraints, Alekseyev managed to preserve much of Ostrovsky's original wit and social commentary, creating a film that entertained while subtly commenting on social mobility and the pursuit of happiness.

Visual Style

The film was shot in black and white by cinematographer Vladimir Nikolayev, who employed a straightforward, classical style appropriate for a literary adaptation. The camera work emphasized character interactions and maintained clear visibility of the actors' performances, reflecting the theatrical origins of the material. The lighting design recreated the atmosphere of 19th-century Russian interiors, using naturalistic techniques to suggest the domestic spaces of merchant households. The framing often used medium shots to capture the ensemble performances, with occasional close-ups for emotional moments. While not technically innovative, the cinematography effectively served the story and performances.

Innovations

The film did not introduce significant technical innovations but demonstrated solid craftsmanship within the constraints of Soviet film production in 1951. The technical team successfully recreated 19th-century settings using available resources and standard equipment. The sound recording quality was typical for the period, with clear dialogue reproduction. The film's editing maintained the pacing of the theatrical source while adapting it for cinematic rhythm. The costume and set design teams achieved period authenticity through careful research and resourceful use of materials, contributing to the film's overall effectiveness as a historical adaptation.

Music

The musical score was composed by Lev Schwartz, who created music that complemented the film's 19th-century setting while maintaining a light, comedic tone. The soundtrack incorporated elements of Russian folk music and classical influences appropriate to the period depicted. Schwartz's music enhanced the comedic moments without overwhelming the dialogue or performances. The sound design was typical of Soviet films of the early 1950s, using direct sound recording for dialogue and post-production mixing for music and effects. The musical themes helped establish the social atmosphere and underscored the emotional beats of the story.

Famous Quotes

Truth is good, but happiness is better - as long as you don't have to sacrifice your dignity for it

A general's uniform may look impressive, but it doesn't guarantee a happy marriage

In our family, we don't marry for love, we marry for position

Grandmother knows best what's good for you, even when she doesn't

Money can buy you a husband, but it can't buy you respect

Memorable Scenes

- The scene where Mavra Tarasovna first presents General Babarikin as a potential suitor, showcasing her imperious attitude and social ambitions

- Polyxena's emotional confrontation with her grandmother about her love for Glumov, highlighting the generational and value conflicts

- The comedic dinner scene where all potential suitors and family members interact, revealing their true characters through dialogue and social blunders

- The final resolution scene where social pretensions give way to emotional truths, demonstrating the film's central theme

Did You Know?

- The film is based on Alexander Ostrovsky's 1876 play of the same name, which was one of the playwright's most popular works about merchant class life

- Director Sergei Alekseyev was primarily known as a theater director before transitioning to film, which influenced his theatrical approach to the adaptation

- Evdokia Turchaninova, who played Mavra Tarasovna, was 67 years old during filming and was already a celebrated stage actress with decades of experience in classical Russian theater

- The film was one of the few Ostrovsky adaptations approved for production during Stalin's final years, as his works were sometimes viewed as too critical of Russian society

- Nikolai Ryzhov, who played Amos Panfilovich, had previously appeared in over 40 films before this production and was known for his portrayals of merchant class characters

- The film's release in 1951 coincided with the peak of the Zhdanov Doctrine, which imposed strict cultural guidelines on Soviet arts, making this light comedy somewhat unusual for the period

- The original stage play had been banned for several years after its initial premiere due to its satirical portrayal of Russian merchants

- Valeriya Novak, who played Polyxena, was relatively new to film at the time, having previously worked mostly in theater

- The film's costume department recreated authentic 19th-century merchant class clothing based on historical research and Ostrovsky's original stage directions

- The movie was shot in just three months, which was typical for Soviet productions of this era

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its faithful adaptation of Ostrovsky's classic play and its entertainment value. Reviews in Soviet film journals highlighted the strong performances, particularly Evdokia Turchaninova's portrayal of Mavra Tarasovna, which was described as capturing both the character's comic aspects and her underlying humanity. Some critics noted that the film successfully balanced entertainment with moral lessons about the dangers of social ambition and the importance of genuine happiness. Modern film historians have viewed the adaptation as a competent example of Soviet literary adaptation, noting how it navigated the censorship constraints of the period while preserving the essential spirit of Ostrovsky's work.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by Soviet audiences upon its release in 1951. As a comedy based on familiar classical literature, it provided welcome entertainment during a period when many Soviet films were heavily ideological. Audiences appreciated the performances of the veteran actors and the film's humorous take on social pretensions. The movie's themes of love versus social status resonated with viewers, and its relatively light tone made it popular among diverse age groups. While not as commercially successful as some other Soviet comedies of the era, it maintained a steady audience following and was occasionally revived in Soviet theaters throughout the 1950s.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were recorded for this film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Alexander Ostrovsky's original 1876 play

- 19th-century Russian literary tradition

- Soviet theatrical adaptation techniques

- Classical Russian comedy traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later Soviet adaptations of Ostrovsky works

- Soviet family comedies of the 1950s

- Television adaptations of classical Russian literature

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved in the Russian State Film Archive (Gosfilmofond) and is considered to be in good condition for its age. Digital restoration efforts have been undertaken to ensure its continued availability for historical and cultural purposes.