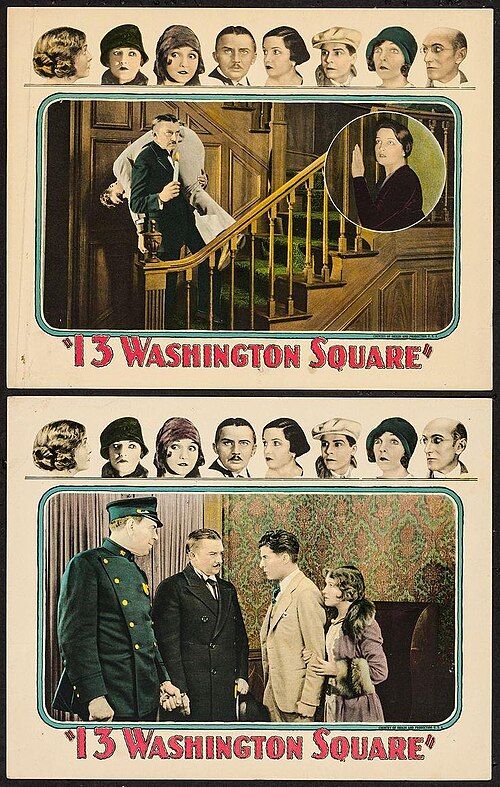

13 Washington Square

Plot

In this silent comedy of manners, wealthy socialite Mrs. Van Derpool is horrified when she discovers her son John intends to marry Mary, a humble working-class girl from the wrong side of town. Determined to prevent the match, Mrs. Van Derpool employs various schemes to separate the young couple, including attempting to introduce John to more suitable society girls and trying to discredit Mary's character. Meanwhile, Mary's down-to-earth honesty and genuine affection for John begin to win over even the most skeptical members of the Van Derpool household. The film culminates in a series of comedic misunderstandings and revelations that force both families to confront their prejudices about class and social standing. Ultimately, love triumphs over social convention in this charming tale that satirizes the rigid class divisions of 1920s high society.

About the Production

The film was produced during the transitional period between silent and sound cinema, when studios were still investing heavily in silent productions while simultaneously converting to sound facilities. Director Melville W. Brown was known for his efficient shooting style and ability to complete productions quickly and under budget, which made him valuable to Columbia Pictures during this period of industry uncertainty.

Historical Background

The year 1928 marked a pivotal moment in American cinema history, representing the final full year of silent film dominance before sound completely revolutionized the industry. The Jazz Singer had already demonstrated the commercial potential of talking pictures in 1927, and studios were racing to convert their facilities and talent to accommodate sound technology. This period also saw the height of the Roaring Twenties, a time of unprecedented prosperity and social change in America, though this economic boom was about to end dramatically with the 1929 stock market crash. Class tensions were a recurring theme in popular culture during this era, as the gap between rich and poor widened and traditional social hierarchies began to be questioned. The film's focus on class conflict and romantic relationships across social divisions reflected contemporary societal concerns and the gradual breakdown of rigid class structures in American life.

Why This Film Matters

As a product of late silent cinema, '13 Washington Square' represents the culmination of the silent comedy genre's evolution, incorporating sophisticated visual storytelling techniques developed throughout the 1920s. The film's exploration of class themes reflects the growing social consciousness in American popular culture during the late 1920s, a period when traditional class divisions were beginning to soften. The movie also serves as an example of Columbia Pictures' early efforts to establish itself as a major studio through the production of commercially viable genre films. While not as groundbreaking as the works of Chaplin or Keaton, the film contributes to our understanding of how mainstream Hollywood studios approached comedy and social commentary during the silent era. The casting of established stars like Alice Joyce alongside rising talents like Zasu Pitts illustrates the transitional nature of the film industry during this period, as studios balanced established draws with emerging performers.

Making Of

The production of '13 Washington Square' took place during a tumultuous period in Hollywood history, as studios grappled with the transition to sound technology. Columbia Pictures, still a relatively minor studio compared to giants like MGM and Paramount, was particularly cautious about investing in expensive sound conversion. Director Melville W. Brown was chosen specifically for his reputation for completing films quickly and economically. The cast included established silent era stars like Alice Joyce, who was nearing the end of her career, alongside rising comedic talent Zasu Pitts. Filming took place primarily on Columbia's modest studio lot in Los Angeles, with second unit photography capturing establishing shots of New York City to lend authenticity to the setting. The production faced the typical challenges of silent filmmaking, including the need for exaggerated physical comedy and facial expressions to convey emotion and humor without dialogue.

Visual Style

The cinematography of '13 Washington Square' employed the sophisticated visual techniques that had become standard in late silent cinema, including dynamic camera movements and expressive lighting to enhance the storytelling. The visual contrast between the opulent world of the wealthy Van Derpool family and the modest surroundings of the working-class characters was emphasized through careful set design and lighting choices. The film utilized the soft-focus techniques popular in the late 1920s to create a romantic atmosphere, particularly in scenes featuring the young couple. The cinematographer made effective use of shadows and light to underscore the class divisions central to the film's theme, with wealthy characters often shot in bright, glamorous lighting while working-class scenes employed more naturalistic lighting. The film's visual style reflects the maturation of silent film cinematography, moving away from the more static compositions of earlier years toward a more fluid and expressive visual language.

Innovations

While '13 Washington Square' was not a groundbreaking film in terms of technical innovation, it benefited from the technical advancements that had become standard in late silent cinema. The film utilized the improved film stocks of the late 1920s, which offered better image quality and allowed for more sophisticated lighting techniques. The production employed the latest camera equipment available to Columbia Pictures, enabling smoother camera movements and more dynamic visual compositions than earlier silent films. The film's editing demonstrates the sophisticated understanding of rhythm and pacing that had developed in silent cinema, with well-timed cuts enhancing the comedic timing of key scenes. The set design and art direction took advantage of the more elaborate production techniques available in 1928, creating convincing representations of both high society and working-class environments. While not technically innovative, the film represents the polished craftsmanship that characterized mainstream Hollywood production at the end of the silent era.

Music

As a silent film, '13 Washington Square' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The typical presentation would have featured a theater organist or small orchestra performing appropriate music to enhance the emotional impact of each scene. The score would have included popular songs of the era as well as classical pieces adapted to fit the film's mood and action. Musical cues would have been provided by the studio to theater musicians, indicating the type of music appropriate for each scene. The film's romantic elements would have been underscored with lush, melodic themes, while comedic moments would have been accompanied by lighter, more playful musical selections. The transition to sound technology was already underway when this film was released, so some theaters may have experimented with synchronized sound effects or musical accompaniment, though the film itself was produced as a traditional silent picture.

Did You Know?

- This was one of the last silent films released by Columbia Pictures before the studio fully converted to sound production in 1929.

- Jean Hersholt, who plays the wealthy matron's husband, was one of the few actors who successfully transitioned from silent films to sound pictures, later becoming famous for his role as Dr. Christian in radio and film.

- Alice Joyce, who portrays the wealthy matron, was a major star of the 1910s and early 1920s but this was among her final film appearances before retiring from acting.

- Zasu Pitts, playing the working-class heroine, was one of the most popular comedic actresses of the silent era, known for her distinctive mannerisms and expressive face.

- The film's title refers to the prestigious Washington Square area of New York City, symbolizing the upper-class world the wealthy family inhabits.

- Director Melville W. Brown was primarily known as a comedy director who worked with many of the era's top comedic talents.

- The film was released just months before the stock market crash of 1929, making its themes of class division particularly prescient.

- No complete prints of this film are known to survive in major film archives, making it a partially lost film.

- The production utilized actual New York City locations for establishing shots, a relatively expensive practice for a Columbia production of this era.

- The film's screenplay was adapted from a popular stage play that had been successful in regional theaters across the United States.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of '13 Washington Square' were generally positive, with critics praising the film's light comedic touch and the performances of its lead actors. The New York Times noted that Zasu Pitts brought her 'usual charm and comedic timing' to the role of the working-class heroine, while Variety appreciated the film's 'gentle satire of high society pretensions.' However, some critics felt the plot followed familiar territory and didn't offer much innovation in the class-conflict comedy genre. Modern assessment of the film is difficult due to its incomplete survival status, but film historians who have viewed surviving fragments consider it representative of the solid but unremarkable studio comedies produced by Columbia Pictures during this period. The film is generally regarded as a competent example of late silent comedy craftsmanship, though it lacks the artistic ambition or lasting impact of the era's masterworks.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1928 reportedly responded favorably to '13 Washington Square,' particularly enjoying Zasu Pitts' comedic performance and the film's gentle skewering of wealthy society. The movie performed adequately at the box office for a Columbia Pictures release of this period, though it didn't achieve the blockbuster status of some of the era's bigger productions. Contemporary audience surveys indicated that viewers found the film entertaining and relatable, with its themes of love conquering social prejudice resonating with moviegoers during a time of increasing social mobility in America. The film's release timing, just before the full onset of the sound revolution, meant it reached audiences who were still primarily accustomed to silent entertainment, and its visual comedy style was well-suited to the expectations of silent film enthusiasts. However, the rapid transition to sound in late 1928 and early 1929 meant the film quickly faded from public consciousness as audiences embraced the novelty of talking pictures.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The stage play tradition of romantic comedies

- Earlier silent class-conflict films

- The romantic comedy genre established by directors like Ernst Lubitsch

- Contemporary Broadway comedies about social class

This Film Influenced

- Later sound-era romantic comedies dealing with class themes

- 1930s screwball comedies that continued satirizing high society