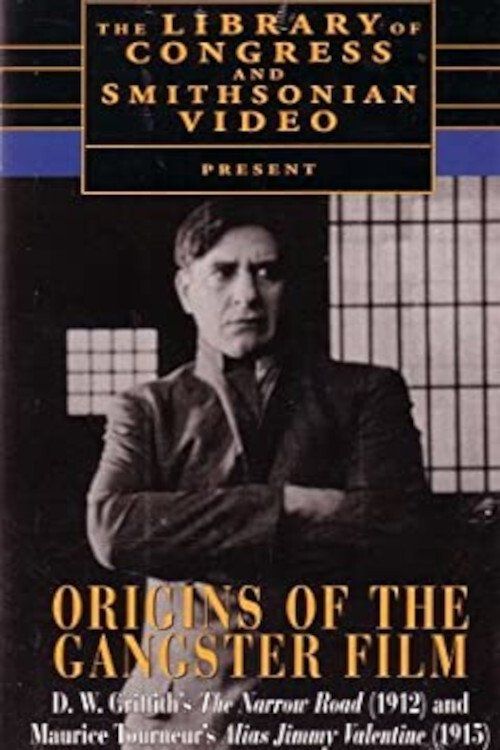

Alias Jimmy Valentine

"A Story of Redemption and the Power of Love"

Plot

Jimmy Valentine, a master safecracker and notorious bank robber, is unexpectedly pardoned from prison through a clerical error. Determined to reform his life, he moves to a new town under an assumed identity and becomes a respected banker, falling in love with the banker's daughter. Just as he's building a legitimate life and planning to marry, a detective from his past recognizes him, threatening to expose his true identity. When a child accidentally locks herself in a bank vault, Jimmy faces a moral dilemma: use his criminal skills to save the child and risk his freedom, or maintain his cover and let tragedy strike.

About the Production

Filmed during the peak of Fort Lee's era as the film capital of America before Hollywood's dominance. Maurice Tourneur brought his sophisticated French cinematic techniques to this American production, using innovative lighting and composition techniques that were ahead of their time. The film featured elaborate bank vault sets and realistic safe-cracking equipment that were considered technically impressive for 1915.

Historical Background

Released in 1915, during a pivotal period in American cinema when feature-length films were becoming the industry standard. The film industry was transitioning from its East Coast roots centered around New York and New Jersey to the emerging Hollywood studio system. World War I was raging in Europe, which disrupted European film production and gave American filmmakers an opportunity to dominate the global market. This period also saw the rise of the star system and the establishment of major studios. The film's themes of redemption and moral choice resonated with Progressive Era audiences interested in social reform and the possibility of personal transformation.

Why This Film Matters

Alias Jimmy Valentine represents an important early example of literary adaptation in American cinema, bringing O. Henry's beloved story to the screen. The film helped establish the crime drama as a viable genre and demonstrated that complex moral themes could be effectively explored in silent cinema. Its exploration of redemption and the possibility of moral rehabilitation reflected Progressive Era beliefs in human perfectibility and social reform. The film's visual sophistication, thanks to Tourneur's direction, helped elevate American cinema's artistic ambitions and influenced subsequent crime films. Its preservation and restoration have made it an important document of early American filmmaking techniques.

Making Of

Maurice Tourneur, already an established director in France, brought his distinctive artistic vision to this American production. He was known for his meticulous attention to visual composition and his use of naturalistic lighting, which set his films apart from the more theatrical style common in 1915. The production faced challenges in creating realistic bank vault sets and safe-cracking equipment, with the studio investing significantly in practical effects. Tourneur worked closely with his actors to achieve more subtle performances than was typical for the period, particularly in the romantic scenes between Warwick and his co-star. The film's success helped cement Tourneur's reputation in America and led to more prestigious projects.

Visual Style

Tourneur employed innovative lighting techniques that were ahead of their time, using natural light and shadows to create mood and depth. The film featured dynamic camera movements that were unusual for 1915, including tracking shots during the safe-cracking sequences. The visual composition showed Tourneur's European artistic training, with carefully framed shots that emphasized psychological tension. The bank vault scenes used dramatic lighting contrasts to create claustrophobic tension. Tourneur also experimented with focus and depth of field to guide audience attention, techniques that would become more common in later years.

Innovations

The film featured impressive practical effects for its safe-cracking sequences, with detailed vault mechanisms that operated convincingly on camera. Tourneur's use of location shooting and realistic set design elevated the production beyond typical studio-bound films of the era. The film demonstrated sophisticated editing techniques, particularly in building tension during the climactic vault scene. Tourneur's innovative use of lighting to create psychological depth was considered groundbreaking. The production also pioneered techniques for filming in confined spaces, particularly during the vault scenes.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The original score likely consisted of popular classical pieces and theater music chosen by the theater's musical director. Typical accompaniment would have included piano or organ music that matched the film's emotional beats, with tense music during the crime scenes and romantic themes for the love story. Some larger theaters might have used small orchestras. The restored version shown today often features newly composed scores by silent film accompanists.

Famous Quotes

A man can change his ways when he finds something worth changing for.

The past is never truly behind us when we carry it in our hearts.

Sometimes the only way to save your future is to use the skills of your past.

Memorable Scenes

- The tense safe-cracking sequence where Jimmy Valentine demonstrates his criminal expertise with elaborate tools and techniques

- The emotional scene where Jimmy faces his moral dilemma upon learning a child is trapped in the vault

- The climactic rescue scene where Valentine must choose between maintaining his cover and saving an innocent life

- The romantic moments between Jimmy and his love interest, showing his desire for a normal life

- The confrontation scene where the detective recognizes Valentine, forcing him to confront his past

Did You Know?

- Based on O. Henry's short story 'A Retrieved Reformation,' one of the earliest literary adaptations of the author's work

- The film was considered lost for decades until a copy was discovered in the 1970s

- Maurice Tourneur was a respected French director who brought European artistic sensibilities to American cinema

- Robert Warwick, who played Jimmy Valentine, was a major Broadway star before transitioning to films

- The film was remade in 1928 as an early sound film starring Rod La Rocque

- The safe-cracking scenes were so realistic that they were reportedly studied by actual criminals

- Tourneur used innovative camera movements and lighting techniques that influenced American filmmaking

- The film's success helped establish World Film Corporation as a major player in early American cinema

- Alec B. Francis, who played the detective, was one of the most prolific character actors of the silent era

- The film was one of the first to explore themes of redemption and rehabilitation in American cinema

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its sophisticated storytelling and Tourneur's skilled direction. The Moving Picture World noted the film's 'unusual dramatic power' and praised Warwick's performance as 'convincing and touching.' Variety highlighted the film's technical achievements, particularly the realistic safe-cracking sequences. Modern critics and film historians have come to appreciate the film as an exemplary work of early American cinema, with Tourneur's visual style and the film's moral complexity earning particular acclaim. The restored version has been featured in film festivals and retrospectives celebrating early American cinema.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a commercial success upon its release, resonating strongly with audiences of the period. Moviegoers were drawn to its combination of thrilling crime elements and heartfelt romance. The story's moral message about redemption struck a chord with Progressive Era audiences. The film's popularity helped establish Robert Warwick as a major film star and contributed to the growing acceptance of feature-length films over shorter one-reel productions. Audience word-of-mouth about the exciting vault-breaking scenes and emotional climax helped sustain the film's run in theaters beyond the typical engagement period of the era.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- O. Henry's 'A Retrieved Reformation'

- French literary cinema

- Progressive Era social reform movements

- European artistic film techniques

This Film Influenced

- Alias Jimmy Valentine (1928 remake)

- The Prisoner of Zenda (1922)

- Various crime dramas of the 1920s

- Early film noir elements

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for many decades but a complete copy was discovered and preserved by the Museum of Modern Art in the 1970s. It has since been restored and is available for archival viewing. The restored version maintains much of its original visual quality, though some deterioration is evident due to age. The film is now considered one of the important surviving examples of Maurice Tourneur's early American work.