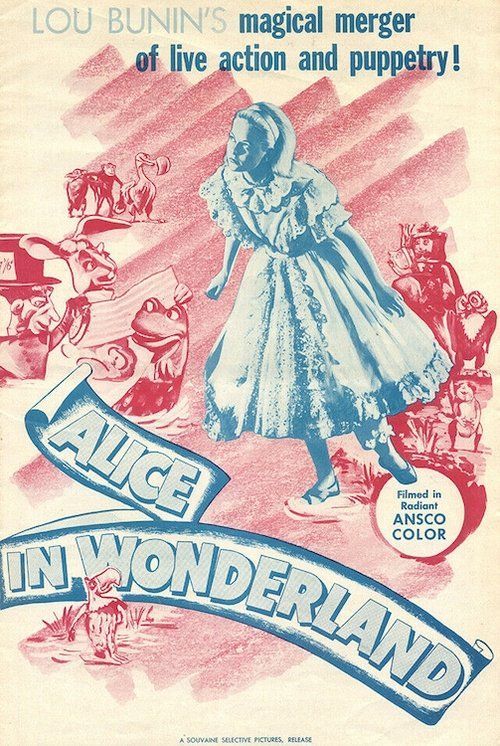

Alice in Wonderland

"A Fantastic Journey Through the Looking Glass of Imagination!"

Plot

Young Alice follows a White Rabbit down a rabbit hole into the fantastical world of Wonderland, where she encounters a series of peculiar characters including the Mad Hatter, the Cheshire Cat, and the Queen of Hearts. As she navigates through this surreal landscape, Alice must make sense of the nonsensical rules and logic that govern Wonderland. The film combines live-action actors with elaborate puppetry to bring Lewis Carroll's beloved characters to life. Alice's journey becomes increasingly bizarre as she attends a mad tea party, witnesses a croquet game with flamingos, and narrowly escapes execution by the temperamental Queen. Eventually, Alice awakens from what seems to be a dream, leaving her to ponder the strange lessons learned in her underground adventure.

About the Production

This production was notable for its innovative combination of live-action actors playing human characters alongside elaborate marionettes for the Wonderland creatures. The puppet sequences were created by the famous puppeteer Lou Bunin, who had previously gained acclaim for his puppet work. The production faced significant technical challenges in seamlessly integrating the live-action and puppet elements, requiring pioneering techniques in matte photography and composite shots. The film was shot in color using the Technicolor process, which was still relatively expensive and rare for British productions at the time.

Historical Background

This film was produced in post-war Britain, a time when the British film industry was struggling to compete with Hollywood productions. The late 1940s saw a surge of creativity in British cinema as filmmakers sought to establish a unique national identity. The decision to adapt Lewis Carroll's quintessentially British work reflected a cultural desire to celebrate English literature and imagination during a period of national rebuilding. The film's innovative use of puppetry and live-action represented British technical ambition and creativity in the face of limited resources compared to American studios. The production also occurred during the early days of television, when cinema was still the primary medium for visual storytelling, prompting filmmakers to create spectacular visual experiences that couldn't be replicated on the small screen.

Why This Film Matters

This adaptation holds a unique place in cinema history as one of the first attempts to bring Carroll's surreal vision to life using mixed media techniques. It demonstrated that puppetry could be a legitimate artistic medium for feature films, paving the way for later works like 'The Dark Crystal' and 'Labyrinth'. The film's British sensibility and adherence to Carroll's original text provided a counterpoint to the more Americanized Disney version that would follow. Its technical innovations in composite photography influenced later fantasy films that needed to integrate different visual elements. The movie also represents an important example of post-war British family entertainment that sought to educate as well as entertain, maintaining the philosophical and satirical elements of Carroll's work rather than simplifying them for young audiences.

Making Of

The production was groundbreaking in its technical approach to combining live-action with puppetry. Director Dallas Bower worked closely with puppeteer Lou Bunin to create a seamless integration between the human actors and puppet characters. The filming process was incredibly complex, often requiring multiple takes to synchronize the actors' performances with the puppet movements. The sets were built on an oversized scale to accommodate the large puppets, with some sets reaching over 20 feet in height. The puppet characters were operated from below the stage through trap doors, with puppeteers working in cramped conditions for hours at a time. The film's color cinematography was handled by Jack Cox, who had to develop new lighting techniques to properly illuminate both the live actors and the puppets without creating shadows that would reveal the puppeteers' presence.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Jack Cox was revolutionary for its time, employing innovative techniques to seamlessly blend live-action with puppet sequences. Cox utilized forced perspective and oversized sets to create the illusion of scale between human actors and puppet characters. The film made extensive use of matte paintings and composite shots to create the fantastical environments of Wonderland. The Technicolor process was used to its full potential, with Cox creating a vibrant color palette that distinguished the real world from the surreal realm of Wonderland. Special lighting rigs were designed to illuminate the puppets without revealing the puppeteers or creating unwanted shadows. The camera work often employed unusual angles and movements to enhance the dreamlike quality of Alice's journey.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was its pioneering integration of live-action and puppetry on a feature-film scale. The production team developed new techniques for composite photography that allowed actors and puppets to appear in the same frame seamlessly. The puppet mechanisms were revolutionary for their time, featuring sophisticated controls that allowed for nuanced expressions and movements. The film also experimented with early forms of motion control photography to ensure consistent camera movements across different elements of composite shots. The oversized set construction required new approaches to set design and lighting to accommodate both human performers and large-scale puppets. The production also pushed the boundaries of Technicolor filming in Britain, requiring specialized equipment and techniques that were not commonly available to British productions at the time.

Music

The musical score was composed by William Alwyn, one of Britain's leading classical composers who also wrote numerous film scores. Alwyn's music incorporated leitmotifs for different characters and used unusual orchestral combinations to create the fantastical atmosphere of Wonderland. The score featured prominent use of harpsichord, celesta, and various percussion instruments to achieve its magical quality. Several musical numbers were included, with the most notable being the Mad Hatter's tea party song. The soundtrack was recorded using the latest magnetic recording technology available in Britain at the time, allowing for better fidelity than standard optical tracks. The film's sound design also included innovative use of echo and reverb to distinguish between the real world and Wonderland.

Famous Quotes

We're all mad here. I'm mad. You're mad. - Cheshire Cat

Off with their heads! - Queen of Hearts

Curiouser and curiouser! - Alice

Why is a raven like a writing desk? - Mad Hatter

I can't go back to yesterday because I was a different person then. - Alice

Memorable Scenes

- The tea party sequence where Alice joins the Mad Hatter, March Hare, and Dormouse for an endless celebration, featuring elaborate puppet choreography and surreal dialogue

- Alice's first encounter with the Cheshire Cat, who appears and disappears leaving only his grin behind

- The Queen's croquet game using flamingos as mallets and hedgehogs as balls

- The opening sequence where Alice follows the White Rabbit down the rabbit hole

- The trial scene where Alice stands up to the Queen of Hearts and grows to giant size

Did You Know?

- This was the first feature-length adaptation of Alice in Wonderland to use a combination of live-action and puppetry

- The film was actually completed in 1946 but faced a three-year delay in release due to distribution complications and competition from Disney's animated version

- Director Dallas Bower was primarily known for his documentary work before taking on this fantasy project

- The elaborate puppet sequences took nearly two years to film and required a team of 15 puppeteers

- Stephen Murray, who played the Narrator, was a distinguished stage actor who rarely appeared in films

- The film's release in the United States was delayed until 1951, after Disney's animated version had already been released

- The Queen of Hearts puppet was over 6 feet tall and required three operators to manipulate

- The film was banned in several countries for being 'too frightening for children'

- Original author Lewis Carroll's niece was consulted during production to ensure authenticity to the source material

- The tea party sequence required over 300 separate puppet movements and took three weeks to film

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's technical ambition and visual artistry, with The Times calling it 'a remarkable achievement in British cinema' and noting its 'daring combination of puppetry and live-action'. However, some reviewers found the tone too dark and unsettling for children, with Sight & Sound criticizing the 'nightmarish quality' of some sequences. Modern critics have reevaluated the film more favorably, recognizing it as an underrated masterpiece of fantasy cinema. The British Film Institute has described it as 'a bold and imaginative interpretation that deserves rediscovery'. The film's reputation has grown over time, particularly among enthusiasts of puppetry and fantasy cinema, who appreciate its artistic courage and technical innovation.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience response was mixed, with many finding the film's surreal imagery and puppet characters unsettling compared to more traditional family films. The three-year delay between completion and release hurt its commercial prospects, as audiences had moved on to other productions. However, the film developed a cult following among fantasy enthusiasts and puppetry aficionados in subsequent decades. Children who saw the film often reported being both frightened and fascinated by its imagery, with many recalling it vividly years later. In recent years, the film has found new audiences through retrospective screenings and home video releases, with modern viewers often expressing surprise at its technical sophistication and artistic ambition.

Awards & Recognition

- Special Jury Prize for Technical Innovation - Venice Film Festival 1949

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Lewis Carroll's 'Alice's Adventures in Wonderland' (1865)

- Victorian puppet theater traditions

- German Expressionist cinema

- British literary adaptation films of the 1940s

This Film Influenced

- Disney's 'Alice in Wonderland' (1951)

- The Dark Crystal (1982)

- Labyrinth (1986)

- The NeverEnding Story (1984)

- Coraline (2009)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the British Film Institute National Archive, though some elements show signs of deterioration. A restoration was completed in 2015 using original Technicolor negatives where available. The film exists in its complete form, though some original soundtrack elements were lost and have been reconstructed from secondary sources. The restoration work revealed the quality of the original cinematography that had been obscured by years of poor quality prints.