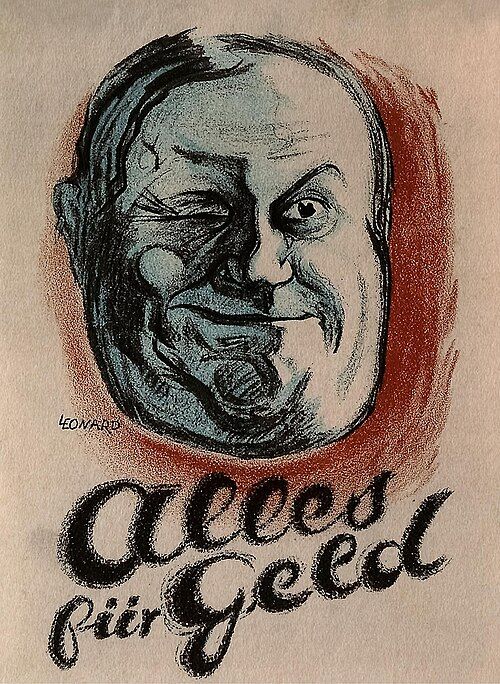

All for Money

Plot

In post-WWI Germany, former butcher-turned-meatpacking magnate Rupp (Emil Jannings) has become wealthy through war profiteering, though he remains crude and uneducated. His beloved son Fred is an automobile enthusiast, while Rupp, now a widower, falls for Helen (Dagny Servaes), a destitute former aristocrat forced to pawn her family heirlooms. Helen accepts Rupp's marriage proposal to secure money for her ailing mother's medical care, despite warnings from her former lover Platen, who holds a grudge against Rupp for firing him after he protected a chorus girl from Rupp's advances. Meanwhile, Rupp's business dealings with the swindler Graf over a bankrupt auto manufacturer Phoenix lead to betrayal and revenge plots, culminating in a dramatic confrontation when Rupp discovers his son begging Helen to reject the marriage and return to Platen.

About the Production

Filmed during the height of German Expressionism, though this film employed more realistic visual styles compared to contemporary expressionist works. The production faced challenges due to the hyperinflation crisis in Germany during 1923, which affected budgeting and resource allocation. Director Reinhold Schünzel, who also wrote the screenplay, adapted the story from contemporary German society's post-war economic realities.

Historical Background

All for Money was produced during the Weimar Republic's most unstable period, the hyperinflation crisis of 1923. When Germany defaulted on its war reparations payments, French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr industrial region, leading to passive resistance and massive currency devaluation. The German mark became virtually worthless, with prices doubling every few hours. This economic chaos created a new class of overnight millionaires and bankrupted the traditional middle and upper classes, perfectly mirroring the film's central conflict between old money and new wealth. The film's release coincided with the introduction of the Rentenmark, which finally stabilized the German economy. Cinema during this period served as both escape and social commentary, with films like this one reflecting the public's fascination and anxiety about rapid social change and the moral implications of wealth accumulation during times of national crisis.

Why This Film Matters

The film stands as an important document of Weimar Germany's social transformation, capturing the tension between traditional aristocratic values and the rise of industrial wealth. It represents a shift from the more stylized German Expressionist films toward social realism, reflecting the New Objectivity movement that was gaining prominence in German arts and literature. The film's portrayal of a crude industrialist's attempt to buy aristocratic status through marriage resonated with contemporary audiences experiencing similar social upheavals. It also contributed to the development of the character study genre in German cinema, with Emil Jannings' performance becoming a template for portraying complex, morally ambiguous protagonists. The film's exploration of how war profiteering created new social hierarchies influenced later German films dealing with similar themes, including some of Fritz Lang's works.

Making Of

The production of 'All for Money' took place during one of Germany's most economically turbulent periods. The hyperinflation crisis of 1923 meant that the film's budget had to be calculated daily as currency values fluctuated wildly. Director Reinhold Schünzel, who also penned the screenplay, drew inspiration from the real-life social dynamics he observed in Berlin's high society and business circles. Emil Jannings, already a major star in German cinema, brought his method acting approach to the role of Rupp, spending time observing actual industrialists and nouveau riche businessmen to capture their mannerisms and speech patterns. The film's automobile sequences were particularly challenging to shoot, as the vintage cars of the era were unreliable and required constant maintenance. The set design for Rupp's mansion was deliberately overdone to reflect the ostentatious taste of newly wealthy industrialists, contrasting sharply with the decaying aristocratic elegance of Helen's former home.

Visual Style

The cinematography, credited to Carl Hoffmann, employed a more naturalistic style than the dramatic lighting typical of German Expressionist films of the period. Hoffmann used soft focus techniques to create emotional depth, particularly in scenes involving Helen's internal conflicts. The film featured extensive location shooting in Berlin, capturing the contrast between the city's industrial areas and aristocratic districts. Interior scenes were lit with a combination of natural and artificial light to create a sense of realism. The automobile sequences utilized innovative tracking shots that followed the vehicles from various angles, showcasing the technical capabilities of German cinematography in the early 1920s. The visual style gradually shifted from the warm, opulent lighting of Rupp's world to the colder, more muted tones of Helen's declining circumstances, reinforcing the film's thematic concerns.

Innovations

The film featured innovative use of location shooting in Berlin, which was still relatively uncommon for German productions of the era. The automobile sequences required specialized camera mounting techniques to capture dynamic movement shots. The production employed early forms of makeup aging techniques to show the passage of time and the physical toll of stress on characters. The film's editing, supervised by Schünzel, used cross-cutting techniques to build tension between parallel storylines, particularly effective in the climactic scenes. The set design incorporated practical effects for the industrial sequences, including working machinery and authentic-looking production facilities. The film also experimented with different film stocks to achieve varied visual textures for different social environments.

Music

As a silent film, 'All for Money' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The score was typically provided by a theater's house orchestra or pianist, who would adapt popular classical pieces and contemporary musical themes to match the on-screen action. For dramatic scenes, pianists often used works by composers like Chopin or Brahms, while more tense moments might feature dissonant modernist compositions. The film's original cue sheets, if they existed, have not survived, but contemporary theater programs suggest that German theaters typically used a mix of Wagnerian leitmotifs for character themes and popular songs of the era for lighter moments. The automobile sequences were often accompanied by upbeat, rhythmic music to convey the excitement and modernity of the new technology.

Famous Quotes

Money can buy everything but respectability

In these times, even love has its price

The old ways are dying, and new men are rising from the ashes of war

You cannot buy a title, but you can buy the man who holds one

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic confrontation when Rupp discovers his son begging Helen not to marry him, revealing the family's internal conflicts and the generational divide

- The scene where Helen pawns her last family heirloom, symbolizing the complete collapse of aristocratic privilege and dignity

- The automobile factory sequence showcasing the modern industrial world that Rupp dominates, contrasting with the decaying aristocratic settings

- The tense dinner scene where Rupp attempts to impress Helen with his wealth while displaying his crude manners, highlighting the class divide

Did You Know?

- The original German title was 'Alles für Geld' (literally 'Everything for Money'), reflecting the film's central theme of materialism in post-war German society.

- Emil Jannings, who plays the crude millionaire Rupp, would later become the first recipient of the Academy Award for Best Actor in 1929.

- Director Reinhold Schünzel was known for his versatility, working as both actor and director, and later had a successful career in Hollywood after fleeing Nazi Germany.

- The film was produced during the devastating hyperinflation period in Germany (1923), when money literally lost value by the hour, making the film's themes particularly relevant to contemporary audiences.

- Dagny Servaes, who plays Helen, was an Austrian actress who worked extensively in German cinema during the silent era.

- The automobile company 'Phoenix' mentioned in the plot was likely inspired by real German automotive companies struggling after WWI.

- The film's exploration of class tensions reflected the social upheaval in Weimar Germany, where old aristocratic values clashed with new money and changing social structures.

- Reinhold Schünzel reportedly used natural lighting techniques influenced by contemporary Scandinavian cinema rather than the more dramatic artificial lighting common in German films of the era.

What Critics Said

Contemporary German critics praised the film for its realistic portrayal of post-war German society and Emil Jannings' powerful performance. The film review publication 'Film-Kurier' noted that Schünzel had 'captured the essence of our troubled times' through his nuanced character studies. Critics particularly appreciated how the film avoided melodramatic excess while still maintaining dramatic tension. The Berlin newspaper 'Vossische Zeitung' highlighted the film's social relevance, stating it 'holds a mirror to the moral decay accompanying our economic chaos.' Modern film historians have reassessed the work as an important transitional piece between German Expressionism and the New Objectivity movement, though some contemporary critics note that its pacing may seem slow to modern audiences accustomed to faster narrative development.

What Audiences Thought

The film found moderate success with German audiences in 1923, particularly appealing to middle-class viewers who could relate to the social upheaval depicted. The theme of old versus new money resonated strongly with audiences who had experienced similar social transformations in their own communities. Emil Jannings' star power drew significant crowds, with theaters reporting full houses during the film's initial run in Berlin and other major German cities. However, the film's serious tone and social commentary meant it didn't achieve the same popular success as more escapist entertainment of the period. Audience letters published in film magazines of the era show that viewers particularly connected with the moral dilemmas faced by Helen's character, debating whether her decision to marry for money was justified by her circumstances.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionism (transitional phase)

- New Objectivity movement

- Contemporary German literature

- Scandinavian naturalism

- American business dramas

This Film Influenced

- The Joyless Street (1925)

- The Last Laugh (1924)

- The Blue Angel (1930)

- Variety (1925)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is believed to be partially lost, with only fragments and incomplete reels surviving in various European film archives. The Bundesarchiv in Berlin holds approximately 45 minutes of footage, while the Cinémathèque Française has additional fragments. A restoration project was attempted in the 1970s but was incomplete due to missing material. Some scenes exist only as still photographs and production stills. The film's preservation status reflects the unfortunate loss rate of German silent films, estimated at over 80% for productions of this era.