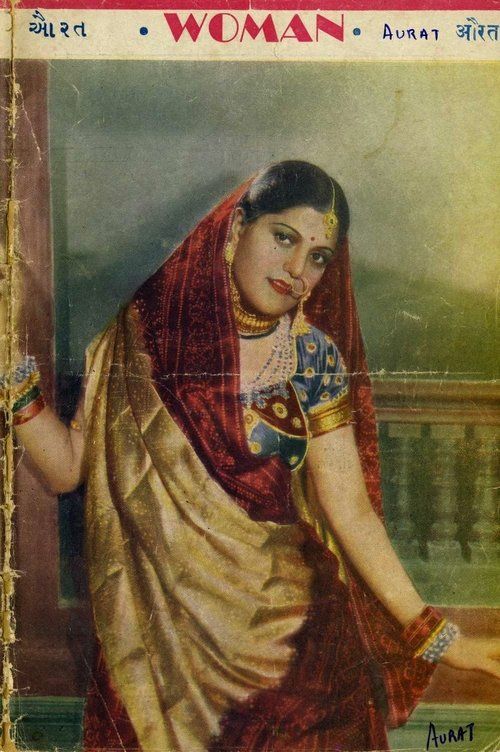

Aurat

"The Eternal Mother - Her Sacrifice, Her Suffering, Her Love"

Plot

Aurat tells the powerful story of Radha, a determined mother in rural India who faces overwhelming challenges while raising her two sons alone after her husband abandons the family. Struggling against extreme poverty and the predatory advances of Sukhilala, a lecherous money lender who demands sexual favors in exchange for food, Radha maintains her dignity through back-breaking labor and unwavering maternal devotion. Her sons grow up with starkly different personalities - the elder Birju becomes rebellious and angry at their social injustice, while the younger Ramu remains gentle and obedient despite their hardships. The narrative reaches its emotional climax when Birju, unable to tolerate his mother's suffering and the village's oppression, turns to violence and ultimately faces tragic consequences for his actions. Through Radha's journey of sacrifice, resilience, and maternal love, the film explores the devastating impact of poverty on family dynamics and the human spirit's capacity to endure despite overwhelming adversity.

About the Production

Mehboob Khan faced significant challenges creating realistic rural sets within the studio limitations of 1940s Bombay cinema. The film was made during a period of transition in Indian cinema, moving away from theatrical influences toward more realistic storytelling. The production team reportedly spent considerable time researching rural life to ensure authenticity in depicting the struggles of peasant families.

Historical Background

Aurat was produced during a pivotal period in Indian history, just seven years before independence and during the height of the Quit India Movement's precursor activities. The 1940s were marked by severe economic depression in rural India, with the impact of World War II exacerbating food shortages and poverty. The film's depiction of money lenders exploiting poor farmers reflected a real social crisis that was contributing to rural unrest and supporting the independence movement's narratives about British economic exploitation. Indian cinema in 1940 was transitioning from the influence of Parsi theater toward more socially relevant themes, with directors like Mehboob Khan leading this change. The film emerged during the studio era of Bombay cinema, when large production houses dominated the industry and were beginning to explore more serious subject matter beyond entertainment. The pre-independence period also saw growing consciousness about women's issues, making Aurat's focus on a mother's struggle particularly resonant with contemporary audiences.

Why This Film Matters

Aurat holds immense cultural significance as a foundational text of Indian cinema's social realist tradition. The film established the template for the 'Mother India' archetype that would become central to Indian cultural narratives, representing the nation as a suffering yet resilient maternal figure. Its exploration of rural poverty and exploitation helped legitimize social themes as commercially viable subjects in mainstream Indian cinema. The film's influence extends beyond cinema to literature and political discourse, with the character of Radha becoming a reference point for discussions about women's roles in Indian society. Aurat also pioneered the use of cinema as a medium for social commentary in India, inspiring generations of filmmakers to address pressing social issues through popular entertainment. The film's remake as Mother India in 1957 amplified its cultural impact, making the story one of the most retold narratives in Indian popular culture. Its themes continue to resonate in contemporary discussions about rural development, women's empowerment, and social justice in India.

Making Of

The production of Aurat was marked by Mehboob Khan's obsessive attention to detail and authenticity. He reportedly spent months in rural villages observing the daily lives of peasant families to accurately portray their struggles. The casting of his wife Sardar Akhtar as Radha was both a practical and artistic decision, as he believed she could bring the necessary emotional depth to the role. The film's production coincided with the growing Indian independence movement, and Mehboob Khan subtly incorporated nationalist themes without being overtly political. The village sets were meticulously constructed to resemble actual rural Maharashtra, with the production team importing authentic props and costumes from villages. The filming process was challenging due to the technical limitations of 1940s Indian cinema, particularly in capturing outdoor scenes and creating realistic weather effects. Mehboob Khan pushed his crew to innovate with camera techniques to achieve more naturalistic performances, moving away from the static, theatrical style common in Indian films of the era.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Aurat, handled by Faredoon Irani, was notable for its attempt at realism in an era dominated by studio-bound artificiality. Irani employed natural lighting techniques for outdoor sequences, creating a more authentic visual representation of rural India. The camera work showed early signs of the fluid movement that would later characterize Mehboob Khan's films, with more dynamic compositions than typical of 1940s Indian cinema. The cinematography effectively contrasted the harshness of the rural landscape with the warmth of family relationships. Visual metaphors were used throughout, particularly in scenes showing Radha's connection to the land and her isolation against vast, empty spaces. The film's visual style influenced subsequent Indian films dealing with rural subjects, establishing a visual language for representing peasant life on screen.

Innovations

Aurat achieved several technical milestones for its time, particularly in its approach to sound recording and location shooting. The film pioneered the use of synchronized sound in outdoor sequences, creating more natural audio environments than studio recordings. The production team developed innovative techniques for creating realistic weather effects, particularly for sequences depicting drought and hardship. The film's editing, by Bimal Roy (who would later become a renowned director), showed advanced techniques for maintaining narrative continuity across complex emotional sequences. The makeup and costume departments achieved notable realism in depicting the physical effects of poverty and hard labor on the characters. These technical innovations, while subtle, contributed significantly to the film's overall impact and influenced subsequent productions in Indian cinema.

Music

The music for Aurat was composed by Anil Biswas, with lyrics by Safdar Aah. The soundtrack featured several songs that became popular, though they were integrated more naturally into the narrative than was typical for films of the era. The music emphasized folk traditions of rural India, using instruments and melodies that reflected the film's setting. Songs like 'Dukh Ke Din Ab Beetat Nahin' captured the emotional core of the narrative and became enduring classics. The score eschewed the ornate orchestral arrangements common in contemporary films in favor of simpler, more authentic musical expressions. The soundtrack's success helped establish Anil Biswas as a major composer in Indian cinema and influenced the use of music in subsequent social realist films.

Famous Quotes

A mother's heart is a patchwork of love, sacrifice, and endless worry.

Poverty doesn't just empty your stomach, it hollows your soul.

When a mother cries, the heavens must listen.

In the drought of life, a mother's tears are the only rain.

We are born poor, but we don't have to die poor in spirit.

Memorable Scenes

- Radha's defiant stand against the money lender when he demands inappropriate favors in exchange for grain, showcasing her unwavering dignity despite extreme hunger

- The emotional climax where Birju confronts the village authorities, leading to his tragic fate and Radha's ultimate sacrifice

- The sequence where Radha carries her children through the barren landscape during a drought, symbolizing both physical and emotional journey

- The scene where Radha teaches her sons the difference between right and wrong despite their desperate circumstances

Did You Know?

- Aurat was later remade by Mehboob Khan as Mother India (1957), which became one of the most iconic films in Indian cinema history and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

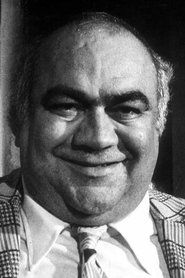

- The character of Radha was played by Sardar Akhtar, who was married to director Mehboob Khan at the time

- The film established Mehboob Khan's signature style of focusing on rural themes and strong female protagonists

- Aurat was one of the earliest Indian films to address social issues like poverty, money lending exploitation, and women's struggles in such depth

- The film's success helped launch the career of actor Surendra, who played one of the sons

- Unlike many films of the era, Aurat featured minimal musical interruptions, with songs integrated more naturally into the narrative

- The film was made during the peak of the Indian independence movement, subtly reflecting nationalist themes through its portrayal of rural suffering

- Mehboob Khan considered Aurat one of his most personal projects, drawing inspiration from his own observations of rural poverty during his childhood

- The original negative of the film is reportedly lost or severely damaged, making complete preservation difficult

- The character of the money lender Sukhilala became an archetype in Indian cinema, representing predatory capitalism in rural settings

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of Aurat was largely positive, with reviewers praising its bold social themes and realistic portrayal of rural life. Critics of the time noted Mehboob Khan's departure from conventional entertainment cinema toward more meaningful storytelling. The film's emotional power and Sardar Akhtar's performance were particularly highlighted in reviews of the era. Modern critics and film historians recognize Aurat as a groundbreaking work that established important precedents in Indian cinema. Many consider it superior to its more famous remake Mother India in terms of raw emotional power and authenticity. Film scholars often cite Aurat as an early example of Indian parallel cinema, despite being made within the commercial studio system. The film is now studied in academic contexts for its pioneering approach to social realism and its influence on subsequent Indian cinema. Critics note that while some technical aspects appear dated by modern standards, the film's emotional core and social commentary remain remarkably relevant.

What Audiences Thought

Aurat was reportedly well-received by audiences upon its release, particularly in rural areas where viewers found authentic representation of their struggles. The film's emotional narrative resonated strongly with contemporary audiences, many of whom were experiencing similar economic hardships. Word-of-mouth helped the film achieve commercial success in various regions, despite its serious themes. Audiences were particularly moved by the mother-son relationships and the moral dilemmas faced by the characters. The film's success established Mehboob Khan as a director who could combine social relevance with popular appeal. Over the decades, Aurat has maintained its reputation among cinema enthusiasts and is frequently referenced in discussions about classic Indian cinema. The film's legacy has been somewhat overshadowed by its remake Mother India, but among film connoisseurs, Aurat is often regarded as the more authentic and powerful version of the story.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Contemporary Indian social reform movements

- Russian realist cinema

- Italian neorealism (predecessor influences)

- Traditional Indian folk narratives

- Parsi theater melodrama (transcended)

- Contemporary literature on rural poverty

This Film Influenced

- Mother India (1957) - direct remake by the same director

- Do Bigha Zameen (1953)

- Garam Hawa (1973)

- Ankur (1974)

- Paar (1984)

- Matrubhoomi: A Nation Without Women (2003)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Aurat is considered partially preserved, with significant challenges to its complete restoration. The original negatives are reportedly lost or severely damaged, a common fate for Indian films of the 1940s due to inadequate preservation facilities and the nitrate film stock used during that period. Some fragmented prints exist in the archives of the National Film Archive of India, but they are incomplete and show significant deterioration. The Film Heritage Foundation has attempted restoration work, but the poor condition of surviving elements makes complete reconstruction difficult. Some portions survive in 16mm prints that were made for exhibition in smaller towns. The film's cultural significance has led to ongoing efforts to locate and preserve any remaining elements, though a complete, pristine version may no longer exist.