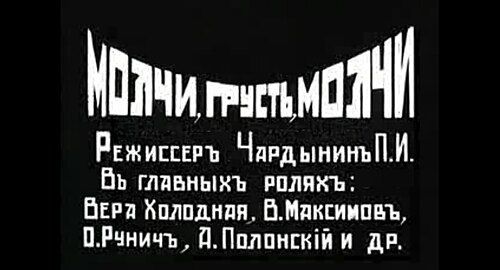

Be Silent, My Sorrow, Be Silent

Plot

Paula, a talented circus performer, is married to Lorio, a clown-acrobat whose life is consumed by alcoholism. During a circus performance, Lorio's drunken state leads to a catastrophic accident that leaves him severely injured and permanently crippled. No longer able to perform in the circus, the couple is forced to take to the streets as musicians to survive. The film explores their struggles with poverty, shame, and the deterioration of their relationship as they face the harsh realities of life outside the circus world. Their journey becomes a poignant examination of love, sacrifice, and the devastating consequences of addiction in early revolutionary Russia.

About the Production

Filmed during the tumultuous period of the Russian Revolution, this production faced significant challenges including limited resources, political instability, and the eventual nationalization of the Russian film industry. The film was one of the last major productions of the Khanzhonkov Company before it was absorbed by the new Soviet state. Director Pyotr Chardynin also acted in the film, a common practice in early Russian cinema. The production utilized actual circus performers for authenticity in the circus sequences.

Historical Background

This film was created during one of the most turbulent periods in Russian history - the immediate aftermath of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. The year 1918 saw Russia descending into full-scale civil war, with the Bolsheviks struggling to consolidate power against multiple opposition forces. The film industry, which had flourished under the Tsarist regime, was in complete disarray. Many studios were nationalized, and private companies like Khanzhonkov faced imminent government takeover. The film's themes of poverty, addiction, and social collapse reflected the harsh realities facing ordinary Russians during this time. The circus setting was particularly poignant, as circuses had been popular entertainment venues under the Tsarist regime but were now seen as bourgeois decadence by the new Soviet authorities. This film represents one of the last examples of pre-revolutionary Russian melodrama before the Soviet film aesthetic was fully established by figures like Eisenstein and Pudovkin.

Why This Film Matters

'Be Silent, My Sorrow, Be Silent' holds immense cultural significance as one of the final works of Vera Kholodnaya, who remains an iconic figure in Russian cinema history. The film represents the apex of the Russian melodramatic tradition that flourished before the Soviet era, showcasing the emotional intensity and psychological depth that characterized pre-revolutionary Russian art. Its exploration of themes like addiction, poverty, and marital strife demonstrated a willingness to tackle social issues that would later become central to Soviet cinema, albeit from a more individualistic, less ideological perspective. The film's title became part of Russian cultural lexicon, symbolizing the stoic suffering that would come to be associated with the Russian character. As a document of its time, it provides invaluable insight into the artistic sensibilities and social concerns of Russians during the revolutionary period, capturing the transition from imperial to Soviet culture.

Making Of

The production of 'Be Silent, My Sorrow, Be Silent' took place under extraordinary circumstances. Filming began in early 1918, just months after the Bolshevik Revolution had completely transformed Russian society. The Khanzhonkov Company, once the most prestigious film studio in the Russian Empire, was struggling to maintain operations amid political chaos, resource shortages, and the looming threat of nationalization. Director Pyotr Chardynin, who also played a supporting role in the film, had to work with severely limited film stock and equipment. The cast and crew often faced delays due to military checkpoints and sporadic fighting in Moscow. Vera Kholodnaya, despite her superstar status, continued to work through these difficult conditions, demonstrating remarkable professionalism. The circus sequences required extensive rehearsals, as they involved actual circus equipment and performers who were themselves struggling to adapt to the new regime. The film's melancholic tone may have reflected the very real despair felt by many Russian artists and intellectuals during this period of cultural upheaval.

Visual Style

The cinematography, credited to the Khanzhonkov studio team, employed the sophisticated visual techniques that had become standard in Russian cinema by 1918. The film utilized dramatic lighting contrasts, particularly in the circus sequences where the artificial lighting of the big top created a dreamlike atmosphere. The camera work showed remarkable mobility for its time, with tracking shots following the performers and intimate close-ups capturing the emotional nuances of the actors. The street performance scenes were shot on location in Moscow, providing a valuable documentary record of the city's appearance during the revolutionary period. The cinematographer made effective use of deep focus to establish the spatial relationships between characters in both the circus and street environments. The visual style blended the theatricality of the circus with the gritty realism of the street scenes, creating a powerful visual contrast that underscored the characters' fall from grace.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical innovation, the film demonstrated the high level of craftsmanship that had been achieved in Russian cinema by 1918. The production made sophisticated use of location shooting, which was still relatively rare in world cinema at the time. The circus sequences required complex camera setups to capture the dynamic movement of the performers while maintaining visual clarity. The film employed effective use of depth of field and composition to convey emotional states and social relationships. The makeup and costume design were particularly noteworthy for their realism in depicting the physical deterioration of the alcoholic character. The editing techniques, while conventional by modern standards, showed a sophisticated understanding of rhythm and pacing in building emotional intensity. The film's surviving footage demonstrates the technical sophistication that Russian cinema had achieved just before the revolutionary upheaval that would transform the industry.

Music

As a silent film, 'Be Silent, My Sorrow, Be Silent' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The score likely included popular Russian romances and folk songs of the era, particularly the title song 'Molchi, grust', molchi' from which the film took its name. The circus sequences would have featured lively, upbeat music typical of circus performances, while the dramatic scenes would have been underscored with melancholic piano or organ music. The street performance scenes probably included authentic street music of the period, possibly featuring accordions and balalaikas. The original musical arrangements have been lost, as was common for silent films of this era. Modern screenings of the surviving footage typically use period-appropriate Russian classical music or newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the emotional tone of the original accompaniment.

Famous Quotes

Be silent, my sorrow, be silent... the world doesn't need to hear our pain.

The circus lights fade, but the darkness of the street remains forever.

In every laugh of the crowd, I hear the echo of our broken dreams.

Memorable Scenes

- The catastrophic circus accident where Lorio falls during his performance, captured in a single, unbroken shot that emphasizes the horror and finality of the moment.

- The first street performance scene where Paula and the crippled Lorio play for passing strangers, their humiliation palpable as they struggle to maintain their dignity.

- The intimate moment between Paula and Lorio in their cramped apartment, where she tends to his wounds and they confront the reality of their new life together.

Did You Know?

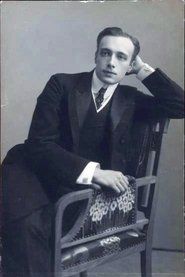

- This was one of the final films starring Vera Kholodnaya, often called 'The Queen of Russian Screen,' before her tragic death from Spanish influenza in 1919 at age 25.

- The film's Russian title 'Молчи, грусть, молчи' (Molchi, grust', molchi) became a cultural phrase in Russia, often quoted in literature and everyday speech.

- Director Pyotr Chardynin was one of the most prolific directors of the Russian Empire, having directed over 100 films between 1908 and 1920.

- The film was produced during the exact period of the October Revolution and subsequent Civil War, making its production and distribution particularly challenging.

- Vera Kholodnaya was the highest-paid actress in Russian cinema at the time, earning an unprecedented salary that rivaled European stars.

- The circus sequences were filmed in a real Moscow circus that had been temporarily converted to a film studio due to the revolution.

- The film's themes of alcoholism and poverty were considered quite daring for the time, especially given the political upheaval occurring in Russia.

- This was one of the last films produced by the Khanzhonkov Company before it was nationalized by the Bolsheviks.

- The surviving portion of the film was discovered in the Soviet film archives in the 1970s, though the second reel remains missing.

- The film's title comes from a popular Russian romantic song of the era, which was likely used as diegetic music in the street performance scenes.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its emotional power and Vera Kholodnaya's exceptional performance. Reviews in Russian film journals of 1918 highlighted the film's realistic portrayal of circus life and its unflinching examination of alcoholism's devastating effects. The film was particularly noted for its atmospheric cinematography and the chemistry between Kholodnaya and her co-stars. Later Soviet critics, writing in the 1920s and 1930s, were more ambivalent, viewing the film as representative of the 'bourgeois sentimentality' that characterized pre-revolutionary cinema. However, film historians in the post-Stalin era have reassessed the film, recognizing its artistic merits and historical importance. Modern critics appreciate the film as a masterpiece of early Russian melodrama and a crucial document of cinematic transition during the revolutionary period.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with Russian audiences in 1918, despite the chaotic conditions of the time. Movie theaters in Moscow and Petrograd were filled with viewers eager to see the latest Vera Kholodnaya film, which provided temporary escape from the hardships of revolutionary life. The film's themes of suffering and redemption resonated deeply with audiences who were themselves experiencing profound social and economic disruption. Many viewers reportedly wept during the street performance scenes, identifying with the characters' struggle for dignity in the face of poverty. The film's success at the box office was remarkable given the circumstances, though exact figures are unavailable due to the collapse of the commercial film industry. In the years following, the film developed a legendary status among film enthusiasts, particularly as more of Kholodnaya's work was lost to time and political purges.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Works of Maxim Gorky

- French melodramatic tradition

- Italian diva films

- Russian literature of the Silver Age

This Film Influenced

- The Circus (1928) by Charlie Chaplin

- La Strada (1954) by Federico Fellini

- Soviet social realist films of the 1930s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with approximately 40-45 minutes of footage surviving from the original 81-minute runtime. The second half of the film, which reportedly contained the resolution of the story, is considered lost. The surviving footage was discovered in the Gosfilmofond archive in Moscow during the 1970s and has been partially restored. The film exists in 35mm format, though some segments show significant deterioration due to age and storage conditions. Film historians continue to search for the missing footage in private collections and international archives, though the chances of finding the complete film grow increasingly remote. The surviving portion provides a valuable, if incomplete, record of this important work of Russian cinema.