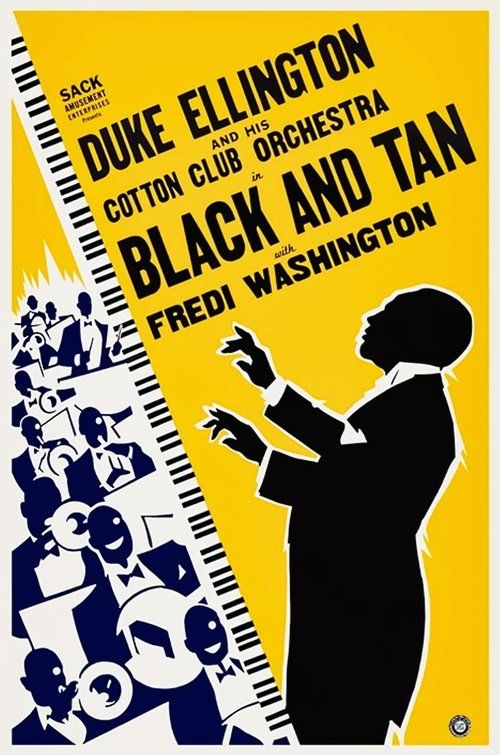

Black and Tan

"A Symphony of the Negro Soul"

Plot

Black and Tan is a poignant musical drama that follows Duke Ellington and his orchestra struggling to make ends meet during the Great Depression. Ellington discovers that his talented dancer friend, played by Fredi Washington, has a serious heart condition but desperately needs the work his band can provide. Despite his pleas for her to rest and protect her health, she insists on performing with the group, knowing it's their only opportunity for employment. In a tragic climax, Washington delivers a passionate dance performance but collapses on stage from the strain, fulfilling Ellington's worst fears. The film concludes with Ellington continuing to play his music, suggesting that art persists even in the face of personal tragedy and economic hardship.

About the Production

Filmed in the early sound era using the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system. The film was produced as one of Warner Bros.' musical short subjects designed to showcase their sound technology and popular musical acts. The production faced challenges with early sound recording equipment, requiring musicians to perform multiple takes to achieve optimal audio quality.

Historical Background

Black and Tan was produced during a pivotal moment in American history and cinema. Released just months after the 1929 stock market crash, it captured the economic struggles facing African American musicians during the Great Depression. The film emerged during the Harlem Renaissance, a period of unprecedented Black cultural achievement in arts, literature, and music. In cinema, 1929 marked the transition from silent films to 'talkies,' with studios scrambling to produce sound content. Warner Bros., having pioneered sound with The Jazz Singer (1927), continued to experiment with musical shorts featuring contemporary performers. The film also reflected the complex racial dynamics of its era, presenting authentic Black culture at a time when Hollywood typically relied on racist caricatures and minstrel traditions.

Why This Film Matters

Black and Tan represents a landmark in African American cinematic representation, presenting Black characters with dignity and complexity rarely seen in mainstream films of its era. The film preserved Duke Ellington's early musical style and performance aesthetic, serving as an invaluable document of jazz history. It challenged contemporary racial barriers by featuring an all-Black cast in a serious dramatic narrative rather than the comic relief roles typically available to Black actors. The film's artistic merit and authentic portrayal of Black life influenced future generations of filmmakers and musicians. Its preservation in the National Film Registry recognizes its importance not only as entertainment but as cultural documentation of the Harlem Renaissance and early jazz culture.

Making Of

Director Dudley Murphy, who had previously worked with avant-garde artists like Man Ray and Fernand Léger, brought an artistic sensibility to this production. The film was made during the transition from silent to sound cinema, presenting technical challenges that required the orchestra to perform live while being filmed. Fredi Washington, despite her light skin, refused to pass as white in Hollywood and was a vocal advocate for better roles for African American actors. The production was filmed on a modest budget typical of short subjects, but Warner Bros. invested in quality production values to showcase their Vitaphone sound system. Ellington and his band had to adapt their usual performance style for the camera, with Murphy encouraging more visual expression to complement the music.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Ray Rennahan employed innovative techniques for capturing musical performance on film. The camera work emphasized the physical expression of the musicians, using close-ups to capture the intensity of their performances. The film utilized dramatic lighting to create mood, particularly in the tragic final sequence. Some scenes were reportedly filmed using early two-strip Technicolor, though most surviving versions are in black and white. The cinematography successfully balanced the requirements of both musical showcase and dramatic narrative, using visual techniques to enhance the emotional impact of both the music and the story.

Innovations

Black and Tan demonstrated several technical innovations for its time. As an early Vitaphone production, it showcased the possibilities of synchronized sound in musical films. The production successfully overcame the technical limitations of early sound recording to capture live musical performance with reasonable clarity. The film experimented with integrating musical numbers seamlessly into dramatic narrative, influencing the development of the musical film genre. The use of camera movement during musical performances was innovative for the era, as early sound films were often static due to technical constraints. Some sequences reportedly employed early color processes, demonstrating Warner Bros.' experimentation with new technologies.

Music

The soundtrack features Duke Ellington and his orchestra performing several of his compositions, including the titular 'Black and Tan Fantasy.' The music represents Ellington's early 'jungle style' period, characterized by exotic harmonies and muted trumpet effects. The score blends hot jazz with blues influences, showcasing the orchestra's unique sound. The recording was made using the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system, which provided surprisingly high audio fidelity for the era. The soundtrack serves both as background music and as an integral part of the narrative, with the lyrics and musical themes reflecting the story's emotional arc. The film preserves some of Ellington's earliest recorded performances, making it historically significant for jazz enthusiasts.

Famous Quotes

Music is my mistress, and she plays second fiddle to no one.

You can't make a living playing music if you're dead.

The music doesn't stop just because someone's heart does.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic dance sequence where Fredi Washington performs with increasing intensity despite her weakening condition, culminating in her dramatic collapse on stage while Ellington continues to play

- The opening scene where Ellington's orchestra struggles through a rehearsal in their cramped apartment, establishing their financial hardship

- The emotional confrontation between Ellington and Washington where he begs her not to perform, showcasing their deep friendship and concern

- The final shot of Ellington alone at the piano, continuing to play as a tribute to his fallen friend, symbolizing music's endurance beyond tragedy

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first films to feature an all-Black cast in a dramatic narrative rather than a minstrel show context

- The film's title refers to the 'Black and Tan' clubs of the Harlem Renaissance, which were racially integrated venues where jazz was performed

- Duke Ellington and his orchestra were actually playing live during filming, as lip-syncing technology was still primitive

- Fredi Washington, who played the dancer, was a prominent civil rights activist and co-founder of the Negro Actors Guild

- The film was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1995 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance

- The 'Cotton Club' sequence features Ellington's signature composition 'Black and Tan Fantasy'

- This short film was considered quite daring for its time in its portrayal of serious illness and death in a Black narrative

- The film was shot in early Technicolor process for some sequences, though most surviving prints are black and white

- Duke Ellington was only 30 years old when this film was made, but already an established bandleader

- The film's tragic ending was unusual for musical shorts of the era, which typically ended on upbeat notes

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its artistic ambition and authentic representation of African American culture. Variety noted that 'the musical numbers are excellent and the dramatic story, though brief, is handled with sincerity.' Modern critics recognize the film as a groundbreaking work that transcended the limitations of its short format. The New York Times retrospective review called it 'a remarkable fusion of jazz and cinema that captures the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance.' Film scholars have analyzed it as an early example of the musical drama genre and as an important document of Black cultural expression in early sound cinema.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by both Black and white audiences upon its release, with particular appreciation for Ellington's musical performances. Harlem audiences reportedly responded enthusiastically to seeing their cultural icons portrayed authentically on screen. The film played in both segregated theaters and integrated venues, reaching diverse audiences. Modern audiences discover the film primarily through film festivals and archival screenings, where it continues to move viewers with its powerful combination of music and drama. Jazz enthusiasts particularly value the film as a rare visual record of Ellington's early orchestra in performance.

Awards & Recognition

- National Film Registry Selection (1995)

- Preserved by the Library of Congress

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Jazz Singer (1927)

- Harlem Renaissance literature

- African American musical theater

- Early Vitaphone musical shorts

This Film Influenced

- Cabin in the Sky (1943)

- Stormy Weather (1943)

- The Cotton Club (1984)

- Mo' Better Blues (1990)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the Library of Congress and selected for the National Film Registry in 1995. While some original elements have been lost, quality prints exist in major film archives including the Library of Congress, UCLA Film & Television Archive, and the Museum of Modern Art. The film has been restored and made available through various educational and archival channels. Some color sequences may be lost, as most surviving versions are in black and white.