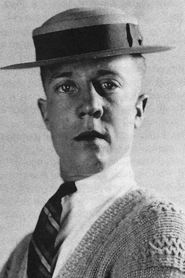

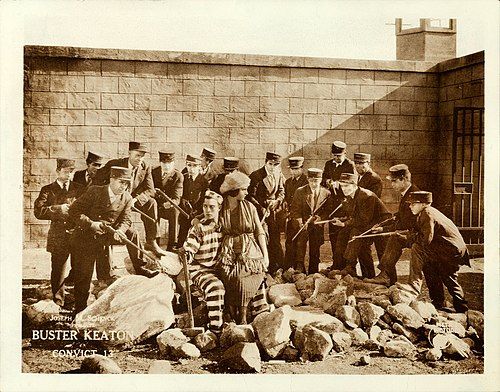

Convict 13

Plot

A young man (Buster Keaton) heads out for a day of golf but encounters an escaped convict who knocks him unconscious and trades clothes with him. Mistaken for the criminal, Buster is arrested and sent to prison where he must adapt to life behind bars with his characteristic deadpan resilience. After surviving various prison mishaps and nearly being executed, Buster helps the warden foil a massive jailbreak attempt. In the chaotic aftermath, he finally clears his name and escapes the prison, only to find himself back on the golf course where his troubles began.

About the Production

Filmed during Keaton's most prolific period where he was producing up to 10 short films per year. The prison set was constructed specifically for this production and featured working cell doors and gallows. Keaton insisted on performing all his own stunts, including the dangerous hanging sequence where he was actually suspended by a hidden harness. The golf scenes were shot on location at a Los Angeles area golf course, requiring special permits as golf courses were relatively rare in 1920.

Historical Background

Convict 13 was released in 1920, a pivotal year in American history marking the beginning of the Jazz Age and the culmination of the Progressive Era. The film industry was transitioning from short comedies toward feature-length productions, though comedy shorts remained popular theater programming. Keaton, having recently left Roscoe 'Fatty' Arbuckle's production company, was establishing his independent studio and artistic voice. The post-World War I period saw audiences craving escapist entertainment, and prison comedies were particularly popular as they allowed for social commentary on authority and institutions while remaining safely humorous. The film's release coincided with Prohibition, adding ironic resonance to its themes of breaking rules and escaping punishment.

Why This Film Matters

Convict 13 represents a crucial development in the evolution of screen comedy, showcasing Keaton's transition from slapstick to more sophisticated physical comedy. The film's prison setting allowed Keaton to explore themes of individual versus institution, a recurring motif throughout his career. Its influence can be seen in countless later prison comedies, from The Marx Brothers' 'Duck Soup' to modern films like 'The Big Lebowski.' The film demonstrated that comedy shorts could contain complete narrative arcs with character development, elevating the medium beyond mere gag reels. Keaton's innovative use of props and environment in this film influenced generations of physical comedians and action directors.

Making Of

Edward F. Cline, who co-directed this film with Keaton (though Keaton was uncredited as director), was a key collaborator during Keaton's early independent period. The film was shot in just four days, typical for Keaton's efficient production methods. The hanging sequence required innovative rigging to create the illusion of Keaton being hanged while actually supporting his weight safely. Keaton's dedication to authenticity led him to spend time observing real prison procedures before filming. The golf scenes proved challenging as early golf equipment was difficult to find in 1920, requiring the production team to source authentic clubs and balls from collectors. The prison set was so realistic that it was reused in several other productions throughout the 1920s.

Visual Style

The cinematography, credited to Elgin Lessley, showcases innovative camera techniques for the era. The film employs dynamic tracking shots during the chase sequences and creative angles during the prison scenes to enhance the claustrophobic atmosphere. Lessley utilized natural lighting for the outdoor golf scenes while creating dramatic shadows in the prison interiors. The hanging sequence features a groundbreaking low-angle shot that emphasizes the height and danger. The camera work maintains Keaton's preferred wide shots, allowing full appreciation of his physical comedy and spatial gags.

Innovations

The film features several technical innovations for its time, particularly in stunt execution and set design. The hanging sequence required a sophisticated hidden harness system that allowed Keaton to appear genuinely suspended while remaining safe. The prison set included functional mechanisms for cell doors and other interactive elements. The film's editing, by Buster Keaton himself, demonstrates advanced continuity techniques that enhance the physical comedy. The golf ball trick shots were achieved through careful timing and camera work rather than special effects, showcasing Keaton's commitment to practical comedy.

Music

As a silent film, Convict 13 was originally accompanied by live musical scores varying by theater. Typical accompaniment included popular songs of 1920, classical pieces, and original improvisation. The film's comedic timing suggests it was designed to work with ragtime and early jazz music. Modern restorations have featured new scores by composers such as Robert Israel and The Alloy Orchestra, who create period-appropriate accompaniment using instruments from the 1920s. The golf scenes often featured lighter, more whimsical music while the prison sequences used more dramatic, tension-building compositions.

Famous Quotes

Buster Keaton's films relied on visual comedy rather than dialogue, but his intertitles included: 'A golf course is the penalty of civilization' and 'Number 13 - Unlucky for some, but not for me!'

Intertitle during the hanging scene: 'This is my last swing - I hope it's a good one!'

Prison intercom intertitle: 'Wanted: One dead or alive convict. Reward: Freedom'

Memorable Scenes

- The iconic hanging sequence where Buster is literally saved by the bell as the prison bell rings at the exact moment of execution, causing the rope to break

- The golf course opening where Buster's terrible golf skills lead to increasingly disastrous results

- The prison cafeteria scene where Buster uses a loaf of bread as a weapon during a food fight

- The climactic jailbreak sequence where Buster inadvertently helps capture the escaping convicts while trying to escape himself

- The final scene where Buster returns to the golf course only to encounter another escaped convict, suggesting the cycle will continue

Did You Know?

- The number 13 in the title refers to Buster's prison number, considered unlucky and adding to the film's comedic tension

- Joe Roberts, who plays the convict, was a former baseball player who stood 6'2" and weighed 300 pounds, creating a stark physical contrast with the 5'7" Keaton

- The hanging scene was considered so realistic that some audience members reportedly fainted during early screenings

- This was one of the first films where Keaton used the 'mistaken identity' trope that would become a recurring theme in his work

- Sybil Seely, who plays the warden's daughter, was one of Keaton's most frequent female co-stars during this period

- The film's production code number was 13, coincidentally matching the title

- Keaton's golf outfit was actually his own personal golfing attire from his real-life hobby

- The prison break sequence involved over 50 extras and took three days to film

- A deleted scene showed Keaton attempting to escape by disguising himself as a woman, but it was cut for pacing

- The film's success led to Keaton receiving a contract increase from First National

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews praised the film's inventive gags and Keaton's 'stone-faced' performance style. Variety noted 'Keaton's remarkable ability to find humor in the most dire circumstances' while Motion Picture News called it 'one of the most clever comedies of the season.' Modern critics recognize Convict 13 as a key example of Keaton's early mastery of cinematic comedy. The film is frequently cited in film studies courses as exemplary of silent-era comedy construction. Critics particularly praise the film's efficient storytelling and the seamless integration of physical comedy with narrative progression.

What Audiences Thought

The film was highly popular with audiences in 1920, playing well in both urban and rural theaters. Audience reaction cards from First National theaters indicated strong positive responses, with particular appreciation for the hanging sequence and prison break scenes. The film's success helped establish Keaton as a bankable star independent of his former partnership with Arbuckle. Modern audiences viewing the film at revival screenings and film festivals continue to respond enthusiastically to its timeless physical comedy and clever situations.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Charlie Chaplin's prison comedies

- Harold Lloyd's thrill comedies

- Mack Sennett's Keystone style

- Fatty Arbuckle's physical comedy format

This Film Influenced

- The General (1926)

- Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928)

- The Prisoner of Zenda adaptations

- Modern prison comedies

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in its complete form at the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. Multiple 35mm copies exist, and the film has been digitally restored by The Criterion Collection and Kino Lorber. The restoration work involved cleaning original nitrate elements and reconstructing missing frames from various sources. The film is considered in excellent preservation condition for a silent-era production.