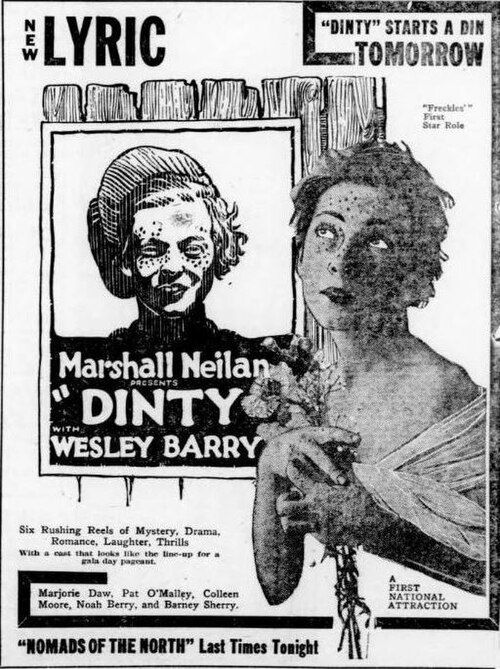

Dinty

"The Plucky Newsboy Who Fought For His Mother's Honor"

Plot

Dinty is a spirited young newsboy struggling to survive on the streets while caring for his ailing mother in a bustling American city. His daily life involves fierce competition with rival newsboys for territory and customers, leading to numerous street fights and confrontations. When his mother's health deteriorates and medical expenses mount, Dinty becomes desperate for money and inadvertently stumbles upon a dangerous drug smuggling operation operating in the city's Chinatown district. The plucky newsboy must use his street smarts and courage to expose the criminals while protecting his mother and himself, ultimately becoming an unlikely hero in his community. The film combines thrilling adventure sequences with comedic moments as Dinty navigates the dangerous criminal underworld while maintaining his youthful optimism and moral integrity.

About the Production

The film was one of Wesley Barry's first leading roles after his breakthrough in 'Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm' (1917). The Chinatown sequences were considered controversial at the time for their depiction of opium smuggling and Chinese criminal elements. Production was reportedly delayed due to Colleen Moore's scheduling conflicts, requiring reshoots of several key scenes. The street fight sequences involving the newsboys were particularly challenging to film, requiring extensive choreography and multiple takes to achieve the desired level of realism without actual injury to the young actors.

Historical Background

'Dinty' was released in 1920, a pivotal year in American history and cinema. The nation was transitioning from World War I into the Roaring Twenties, with significant social changes including women's suffrage, Prohibition beginning in 1920, and rapid urbanization. The film reflected growing concerns about urban crime, drug addiction, and the challenges faced by immigrant families in American cities. In cinema, 1920 marked the period when silent films reached their artistic peak, with longer running times, more sophisticated narratives, and larger budgets becoming standard. The film industry was consolidating in Hollywood, with major studios like Fox Film Corporation establishing dominance. The depiction of Chinatown and drug smuggling in 'Dinty' tapped into contemporary anxieties about immigration, narcotics, and urban decay that were prevalent in post-war America. The film's focus on a working-class child protagonist also reflected the growing popularity of stories about everyday Americans rather than the aristocratic characters that dominated earlier cinema.

Why This Film Matters

'Dinty' represents an important example of the 'street kid' genre that flourished in early American cinema, establishing tropes that would influence countless later films. The film contributed to the popular image of the plucky newsboy as an American archetype, symbolizing the possibility of upward mobility through determination and moral virtue. Its portrayal of urban life, while stereotypical by modern standards, provided audiences of the time with a glimpse into the harsh realities faced by working-class children in rapidly growing American cities. The film's success helped establish Wesley Barry as a major child star and contributed to Colleen Moore's rise to superstardom. The Chinatown sequences, while problematic in their stereotypes, were among the first cinematic depictions of Asian-American communities and reflected both the fascination and fear with which mainstream America viewed these enclaves. The film's themes of family loyalty and moral integrity in the face of corruption resonated strongly with post-WWI audiences seeking reassurance about American values during a period of rapid social change.

Making Of

The production of 'Dinty' took place during a transitional period in Hollywood, as studios were moving from shorter films to feature-length productions. Director John McDermott, primarily known as cinematographer before moving into directing, brought a distinctive visual style to the film, particularly in the dramatic lighting of the Chinatown sequences. The casting of Wesley Barry in the lead role was considered risky, as he was transitioning from supporting child actor roles to leading man status. The street fight scenes were choreographed by former boxer Jack Dempsey, who was a friend of producer William Fox. The production faced significant challenges during filming, including a measles outbreak among the child actors and the need to recreate authentic Chinatown sets after the actual Los Angeles Chinatown refused filming permits due to concerns about negative stereotyping. Colleen Moore's role was expanded during production when studio executives recognized her growing star potential, requiring script revisions and additional shooting days.

Visual Style

The cinematography, likely supervised by director John McDermott who came from a cinematography background, employed the dramatic lighting techniques becoming popular in 1920. The street scenes utilized natural lighting and actual location shooting to create an authentic urban atmosphere, while the Chinatown sequences featured more stylized, low-key lighting to enhance the sense of danger and mystery. Camera movement was relatively static, as was typical of the period, but McDermott incorporated some dynamic shots during the action sequences, including chase scenes filmed from moving vehicles. The film made effective use of the Fox Studio's new artificial lighting equipment, particularly in interior scenes and night sequences. The visual contrast between the bright, open streets where Dinty sells papers and the dark, shadowy interiors of the opium dens creates a visual metaphor for the moral choices facing the protagonist. The cinematography also emphasized the small stature of the child actors through low camera angles, reinforcing Dinty's vulnerability and courage.

Innovations

While 'Dinty' was not a groundbreaking film technically, it demonstrated several advanced techniques for its time. The production made extensive use of location shooting in actual Los Angeles streets and Chinatown, which was still relatively uncommon in 1920. The film employed sophisticated matte paintings to create the illusion of larger cityscapes, particularly in scenes showing the newsboys' territory. The action sequences, including several fights and chase scenes, utilized innovative camera techniques including tracking shots following the characters through crowded streets. The film also featured some early examples of cross-cutting between parallel action lines to build suspense during the climax. The special effects used in the opium den scenes, including smoke effects and dramatic lighting, were considered advanced for the period. The production also utilized the new panchromatic film stock that was becoming available in 1920, which provided better tonal reproduction and more natural skin tones, particularly important for the film's many outdoor scenes.

Music

As a silent film, 'Dinty' would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The original cue sheets, if they existed, have not survived, but typical accompaniment would have included popular songs of the era, classical pieces for dramatic moments, and specially composed themes for the main characters. The newsboy sequences likely featured upbeat, ragtime-influenced music, while the Chinatown scenes would have used exotic-sounding compositions with pentatonic scales to create an 'Oriental' atmosphere. Major theaters would have employed small orchestras, while smaller venues used piano or organ accompaniment. The film's emotional moments, particularly scenes involving Dinty's sick mother, would have been underscored with sentimental ballads popular in the 1920s. Some theaters may have used sound effects devices to enhance the street scenes and action sequences. No original composed score survives, and modern screenings rely on newly commissioned music or period-appropriate selections.

Famous Quotes

A newsboy's gotta be tough, but he's gotta be honest too!

My ma needs this medicine - I'll do whatever it takes!

These streets ain't easy, but they're all we got.

You mess with one newsboy, you mess with all of us!

There's right and there's wrong, and I know which side I'm on.

Chinatown's a dangerous place after dark, especially for kids like us.

A penny saved is a penny earned, but sometimes you gotta risk it all for family.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Dinty's morning routine and his tender care for his sick mother

- The elaborate street fight between rival newsboy gangs, choreographed with authentic period details

- The tense scene where Dinty first discovers the opium smuggling operation in Chinatown

- The climactic rooftop chase through Chinatown with dramatic night photography

- The emotional hospital scene where Dinty must choose between easy money and doing the right thing

- The final newsboy parade celebrating Dinty's heroism and community values

Did You Know?

- Wesley Barry, who played Dinty, was known for his distinctive freckles and became one of the most popular child actors of the silent era

- The film was based on a short story by playwright Charles T. Alden, though the original story has been lost to time

- Noah Beery, who played one of the antagonists, was the father of actor Noah Beery Jr. and brother of Wallace Beery

- Colleen Moore, who had a supporting role, would become one of the biggest stars of the 1920s, earning $12,500 per week by 1927

- The film's depiction of Chinatown and drug smuggling was considered quite daring for its time, though it relied on many stereotypes common in the era

- Several of the young actors playing newsboys were actual former newsboys hired for authenticity

- The film was shot during the Spanish Flu pandemic, which caused production delays and health concerns on set

- A scene involving a rooftop chase across Chinatown buildings required the construction of special platforms and safety nets

- The original negative was reportedly damaged in a 1937 Fox studio vault fire, though copies had already been distributed

- The film's success led to a series of similar 'newsboy' films throughout the early 1920s

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in 1920 were generally positive, with Variety praising Wesley Barry's 'natural and appealing performance' and noting that the film 'combines thrills and humor in an entertaining package.' The Motion Picture News called it 'a fine example of Fox's ability to produce quality family entertainment with strong moral values.' The New York Times review highlighted the film's 'authentic street atmosphere' and 'exciting climax in the opium den.' Critics particularly praised the action sequences and Barry's performance, though some reviewers noted that the Chinatown elements relied on familiar stereotypes. Modern film historians consider 'Dinty' an interesting but typical example of the genre, with most attention focused on its role in the careers of its young stars rather than its artistic merits. The film is rarely mentioned in comprehensive histories of American cinema, being overshadowed by more groundbreaking works of the period, though it is sometimes cited in studies of child actors in silent film.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary audience reception appears to have been strong, with the film performing well in urban markets where newsboy characters resonated with working-class viewers. Theater reports from major cities indicated good attendance, particularly among family audiences. Wesley Barry's popularity among younger viewers was a significant draw, with many newspapers reporting that children especially enjoyed the action sequences and street fight scenes. The film's moral themes and emphasis on family values appealed to parents and progressive era reformers who were concerned about the influence of cinema on young people. However, some Chinese-American community organizations protested the film's stereotypical portrayal of Chinatown and criminal elements, though these protests received limited coverage in mainstream media. The film's success led to increased demand for similar 'plucky kid' stories throughout the early 1920s, though it did not achieve the lasting popularity of other child star vehicles of the era like those featuring Jackie Coogan or Baby Peggy.

Awards & Recognition

- No known awards - the Academy Awards were not established until 1929

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Kid (1921) - Charlie Chaplin's similar themes of a child facing urban hardship

- The Rag Man (1925) - similar newsboy protagonist

- Oliver Twist adaptations - orphaned child facing urban crime

- D.W. Griffith's urban dramas - depiction of city life and moral choices

- The Golem (1920) - influence on dramatic lighting techniques

This Film Influenced

- The Rag Man (1925) - similar newsboy protagonist

- The Kid Brother (1927) - themes of family loyalty and courage

- Little Annie Rooney (1925) - street kid facing urban challenges

- The Street Angel (1928) - urban poverty and redemption themes

- Various newsboy films of the early 1930s including 'Newsboys' Home' (1938)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'Dinty' (1920) is concerning but not completely lost. While the original camera negative was reportedly destroyed in the 1937 Fox vault fire, several 16mm and 35mm copies survived in private collections and archives. The Library of Congress holds an incomplete 35mm print missing approximately 10 minutes of footage. The Museum of Modern Art possesses a more complete but deteriorating 35mm copy that has not been fully restored. Several European archives hold 16mm reduction prints that were distributed internationally in the 1920s. The film has not received a modern restoration or home video release, though bootleg copies circulate among collectors. The surviving prints show significant deterioration, particularly in the dramatic Chinatown sequences where the original lighting effects have been compromised by film degradation. A comprehensive restoration would require combining elements from multiple sources to create the most complete version possible.