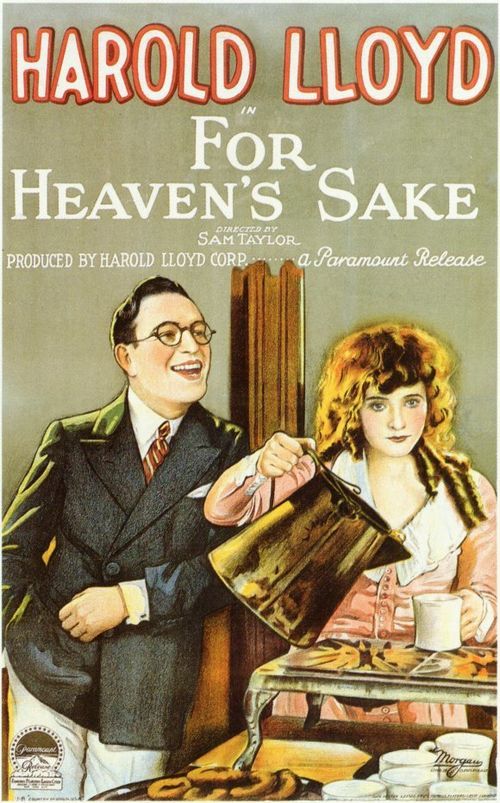

For Heaven's Sake

"The Millionaire Who Learned That Money Can't Buy Everything!"

Plot

J. Harold Manners is a wealthy, carefree young millionaire who lives a life of luxury and irresponsibility in New York City. After accidentally crashing his car into a mission run by Reverend John G. Blake, Harold meets and becomes instantly smitten with the minister's daughter, Hope. Determined to win her affection, Harold donates a million dollars to the struggling mission, but his unconventional methods and lack of understanding of the poor community create chaos and comedy. Through a series of hilarious misadventures, including a wild car chase through the city's poorest district where Harold tries to collect donations, he gradually learns the true meaning of compassion and responsibility. Ultimately, Harold transforms from a selfish playboy into a genuinely caring man who not only wins Hope's love but also earns the respect and acceptance of the community he initially tried to help with his money.

About the Production

The film featured one of Harold Lloyd's most elaborate chase sequences, requiring extensive location shooting in actual downtown districts. The production used real residents of the poorer neighborhoods as extras to add authenticity. Lloyd performed many of his own stunts, including dangerous driving sequences. The mission set was built to scale and designed to look authentic to actual missions of the era.

Historical Background

Released in 1926, 'For Heaven's Sake' emerged during the golden age of silent comedy and the peak of Harold Lloyd's career. The mid-1920s represented the height of silent film artistry before the transition to sound began in 1927-1928. This period saw America experiencing the Roaring Twenties, with economic prosperity and social change reflected in the film's themes of class differences and social responsibility. The film's portrayal of wealth disparity and social consciousness was particularly relevant during an era of growing inequality that would soon culminate in the Great Depression. The mission setting reflected the real social issues of urban poverty and religious charity work prevalent in American cities during the 1920s.

Why This Film Matters

'For Heaven's Sake' represents Harold Lloyd's mastery of the comedy of character development, showing his evolution from pure physical comedy to more nuanced storytelling. The film exemplifies the optimistic American spirit of the 1920s, suggesting that even the wealthiest and most irresponsible could find redemption through genuine compassion. Lloyd's 'glasses character' became an enduring symbol of the common man achieving extraordinary things, influencing countless later comedians. The film's success demonstrated that audiences responded to comedy with heart and social commentary, not just slapstick. It also showcased Lloyd's ability to balance spectacular action sequences with genuine emotional development, a formula that would influence comedy filmmaking for decades.

Making Of

Harold Lloyd was known for his meticulous planning and rehearsal process, often spending weeks perfecting individual gags and sequences. For 'For Heaven's Sake,' the production team scouted actual mission districts in Los Angeles to ensure authenticity. The famous car chase sequence was particularly challenging, requiring coordination between multiple drivers, stunt performers, and camera operators. Lloyd insisted on performing many of his own stunts, believing his timing was crucial to the comedy's effectiveness. The film was shot during the height of Lloyd's popularity, allowing him unprecedented freedom and budget. The production employed over 500 extras for various scenes, particularly the mission sequences. Lloyd's collaborative relationship with director Sam Taylor was well-established, with Taylor understanding exactly how to capture Lloyd's physical comedy to maximum effect. The film's score was composed by Leroy Shield, who created much of the music for Lloyd's films.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by Walter Lundin, employed innovative techniques for capturing both intimate character moments and large-scale action sequences. The film utilized extensive location shooting in downtown Los Angeles, giving it a documentary-like realism that contrasted with the stylized comedy. The car chase sequence featured groundbreaking camera work, including shots from moving vehicles and carefully timed multiple-angle coverage. The lighting design effectively contrasted the bright, luxurious world of Harold's wealth with the darker, more intimate setting of the mission. The film also employed innovative use of deep focus for its time, allowing both foreground and background action to remain sharp during complex scenes.

Innovations

The film featured one of the most elaborate car chase sequences of the silent era, requiring innovative camera mounting techniques and precise timing between multiple vehicles. The production developed new methods for synchronizing action across different locations, particularly challenging for the chase scenes that covered several city blocks. The film also employed early forms of product placement, with Harold's luxury car prominently featured as a character in itself. The mission set construction included working facilities and was designed to be fully functional, allowing for more authentic filming. The production also pioneered new safety measures for stunt coordination, particularly important given Lloyd's insistence on performing his own dangerous driving sequences.

Music

As a silent film, 'For Heaven's Sake' was originally accompanied by live musical performances in theaters, with cue sheets provided to theater organists and orchestras. The suggested score included popular songs of the era as well as original compositions. In 1929, during the transition to sound, the film was re-released with a synchronized soundtrack featuring music by Leroy Shield and sound effects for the action sequences. The re-release version attempted to enhance the comedy with carefully timed sound effects while maintaining the silent film's visual comedy style. The original musical cues emphasized the emotional journey of the characters, with romantic themes for Harold and Hope's relationship and more upbeat, energetic music for the comedy sequences.

Famous Quotes

"I'm going to help these people if it costs me every cent I have!" (intertitle during Harold's transformation)

"Money isn't everything... but it helps!" (early intertitle showing Harold's initial philosophy)

"The best charity is understanding" (final intertitle summarizing the film's theme)

"A million dollars ought to buy something besides trouble!" (intertitle during Harold's frustrations)

Memorable Scenes

- The spectacular car chase sequence through downtown Los Angeles, where Harold attempts to collect donations while being pursued by various characters, showcasing incredible stunt driving and perfectly timed physical comedy

- Harold's first visit to the mission, where his wealth and ignorance clash with the reality of poverty, creating both comedy and social commentary

- The transformation scene where Harold begins to genuinely understand the mission's work and the needs of the community

- The final sequence where Harold uses his wealth creatively to help the mission while demonstrating his personal growth

Did You Know?

- This was Harold Lloyd's most financially successful film of the 1920s, outgrossing even his famous 'Safety Last!'

- The car chase sequence required the closure of several downtown Los Angeles streets for multiple days of filming

- Jobyna Ralston was Harold Lloyd's regular leading lady, appearing in seven of his films

- The film's title was a play on the common phrase 'for heaven's sake,' reflecting both the religious mission setting and the comedic tone

- Harold Lloyd wore his signature glasses character throughout, which had become his trademark persona representing the optimistic American youth

- The mission scenes were filmed on a specially constructed set that was so realistic it attracted actual homeless people during filming

- Noah Young, who played the heavy, was a former Olympic weightlifter and appeared in nine Harold Lloyd films

- The film was re-released in 1929 with a synchronized music score and sound effects during the transition to sound

- Lloyd's production company maintained complete creative control, unusual for the time, allowing him to perfect his comedy timing

- The film's success led to Lloyd building his own studio complex, giving him even more control over future productions

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film as one of Lloyd's best, with Variety calling it 'a laugh riot from start to finish' and particularly noting the effectiveness of the car chase sequence. The New York Times highlighted Lloyd's growth as an actor, noting his ability to convey genuine emotion alongside his trademark physical comedy. Modern critics have reappraised the film as a masterpiece of silent comedy, with many considering it among Lloyd's top three works alongside 'Safety Last!' and 'The Freshman.' The film is frequently cited for its perfect pacing, innovative gags, and successful blend of comedy with heartfelt romance. Critics particularly appreciate how the film uses comedy to address serious social issues without becoming preachy.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with audiences, becoming one of the biggest box office hits of 1926. Theater owners reported packed houses and repeat viewings, with many patrons specifically requesting the car chase sequence to be shown again. The film's success solidified Harold Lloyd's status as the highest-paid film star of the era, earning him over $1.5 million for the year. Audience reaction was particularly enthusiastic to the transformation of Harold's character, with viewers responding emotionally to his journey from selfish playboy to caring humanitarian. The film's popularity extended internationally, with successful runs in Europe and Asia, demonstrating Lloyd's global appeal beyond American audiences.

Awards & Recognition

- Photoplay Magazine Medal of Honor (1926) - Winner

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The social comedies of Charlie Chaplin

- American literary traditions of the self-made man

- Contemporary films about wealth disparity

- Stage comedy traditions of character transformation

- Realist cinema movements showing urban poverty

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent Harold Lloyd films with social themes

- Frank Capra's comedies of the 1930s

- Screwball comedies featuring class differences

- Modern romantic comedies with character transformation arcs

- Films about wealthy protagonists learning social responsibility

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is well-preserved with complete copies held at major archives including the Library of Congress, the UCLA Film & Television Archive, and the Museum of Modern Art. A restored version was released in the 1990s as part of The Harold Lloyd Collection, with improved picture quality and reconstructed original tinting. The film has survived in both its original silent version and the 1929 sound reissue. The preservation quality is excellent, allowing modern audiences to appreciate the film's visual comedy and technical achievements.