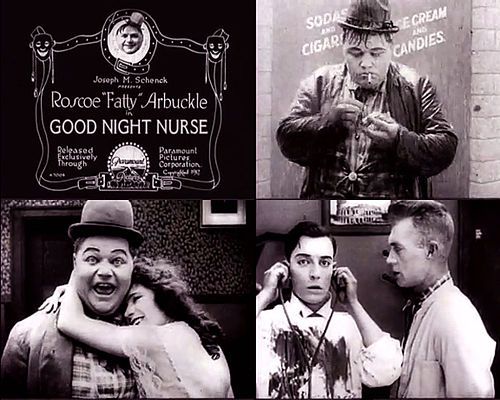

Good Night, Nurse!

"A Laugh Riot from Start to Finish!"

Plot

Roscoe 'Fatty' Arbuckle plays a chronic alcoholic whose wife, fed up with his constant drunkenness, reads about a revolutionary surgical procedure that can cure alcoholism. She has him forcibly admitted to the No Hope Sanitarium, where he's scheduled for the operation. Terrified of the surgery, Roscoe attempts various escape plans but keeps getting caught. In his most desperate move, he disguises himself as a nurse to infiltrate the hospital staff, leading to a series of chaotic and hilarious situations as he tries to avoid detection while plotting his getaway from the medical institution.

About the Production

This was one of the many short comedies produced by Comique Film Corporation, the production company formed by Roscoe Arbuckle and Joseph Schenck. The film was shot during the height of Arbuckle's popularity as one of the highest-paid comedians in Hollywood. The sanitarium set was elaborate for its time, featuring multiple rooms, corridors, and medical equipment to create the authentic hospital atmosphere needed for the comedy.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1918, during the final months of World War I and at the height of the Spanish Flu pandemic. This historical context makes the film's medical setting particularly resonant, as audiences were deeply familiar with hospitals and medical institutions during this time. The early 20th century was also a period of medical experimentation and quackery, with many dubious treatments being marketed to desperate patients. The film's satirical take on medical cures for alcoholism reflected contemporary anxieties about modern medicine while also providing comic relief from the stresses of wartime. Hollywood was rapidly establishing itself as the center of American film production, and comedians like Arbuckle were among the industry's biggest stars, earning salaries comparable to the highest-paid actors of the time.

Why This Film Matters

'Good Night, Nurse!' represents an important milestone in the development of American silent comedy, showcasing the collaborative genius of Arbuckle and Keaton before they became individual stars. The film exemplifies the transition from the more chaotic slapstick of earlier comedies to a more sophisticated style of physical comedy that would define the golden age of silent film. Its hospital setting influenced numerous later comedies that used institutional environments as backdrops for humor. The film also demonstrates how silent comedy could address contemporary social issues like alcoholism through humor, making difficult subjects accessible to mass audiences. The Arbuckle-Keaton partnership documented in this film represents a crucial mentorship relationship that helped shape the future of comedy cinema.

Making Of

The production of 'Good Night, Nurse!' took place during a particularly creative period for Roscoe Arbuckle, who was at the peak of his powers as both a comedian and director. The film was shot quickly, as was typical for comedy shorts of the era, with the entire production likely completed in just a few days. Buster Keaton, who was still learning the craft of filmmaking from Arbuckle, contributed to many of the gags and physical comedy sequences. The hospital set required significant construction and props, with the production team sourcing or creating authentic-looking medical equipment of the period. Arbuckle was known for his improvisational style on set, often developing new gags during filming rather than sticking strictly to scripted material. The film's success led to similar themed comedies featuring institutional settings, which became a popular trope in silent comedy.

Visual Style

The cinematography by George Peters (credited in some sources) employs the standard techniques of silent comedy filmmaking, with clear, well-lit compositions that emphasize the physical comedy. The camera work is functional rather than artistic, designed primarily to capture the performers' actions and reactions clearly. The hospital setting allowed for interesting visual compositions, with long corridors and multiple doorways creating opportunities for complex chase sequences and sight gags. The film uses medium shots for most of the comedy, with occasional close-ups to highlight facial expressions, particularly during Arbuckle's reactions to various medical procedures.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical terms, the film demonstrates the sophisticated studio production techniques that had become standard by 1918. The hospital set construction shows the increasing complexity of studio-built environments in silent comedy. The film makes effective use of editing techniques to enhance the physical comedy, particularly in sequences involving Arbuckle's attempts to escape. The costume work, especially Arbuckle's nurse disguise, shows attention to detail in creating believable visual gags. The film also demonstrates the growing sophistication of gag construction in silent comedy, with multiple payoffs and escalating comic situations.

Music

As a silent film, 'Good Night, Nurse!' would have been accompanied by live musical performances during its theatrical run. The typical score would have been provided by a theater organist or small orchestra, playing popular songs of the era along with classical pieces appropriate to the on-screen action. The hospital scenes would likely have been accompanied by more dramatic or mysterious music, while the comedy sequences would have used upbeat, playful tunes. No original score was recorded for the film, as was standard practice for silent productions of this period.

Famous Quotes

Roscoe (as a nurse): 'I'm the new night nurse - fresh from the factory!'

Doctor: 'This patient requires immediate attention... and possibly a straight jacket!'

Wife: 'I've found the perfect cure for your drinking problem - a complete surgical overhaul!'

Memorable Scenes

- The extended sequence where Arbuckle, disguised as a nurse, attempts to navigate the hospital corridors while avoiding detection by the real medical staff, culminating in a chaotic chase scene through multiple wards and operating rooms.

Did You Know?

- This film features one of the earliest screen appearances of Buster Keaton, who was still developing his 'Great Stone Face' persona while working as Arbuckle's supporting actor.

- The film's title 'Good Night, Nurse!' was a common slang expression in the 1910s used to express surprise or exasperation, similar to modern expressions like 'Oh my God!'

- The sanitarium set was so realistic that some contemporary reviewers commented on the impressive attention to detail in the medical equipment and hospital furnishings.

- Alice Lake, who plays Arbuckle's wife, was a popular actress of the silent era who appeared in over 200 films during her career.

- This was part of a series of Arbuckle-Keaton collaborations that helped establish both comedians as major stars of silent comedy.

- The film's premise about curing alcoholism through surgery was based on real medical quackery that was prevalent during the early 20th century.

- Arbuckle's nurse disguise involved extensive makeup and padding, a technique he would use in several other films.

- The film was released just a few months before the end of World War I, during a period when audiences were hungry for escapist entertainment.

- The comedy relies heavily on physical humor and sight gags, typical of the slapstick style that dominated early silent comedies.

- The film's running time of 25 minutes was standard for comedy shorts of this era, which were typically shown as part of larger theater programs.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'Good Night, Nurse!' for its inventive gags and Arbuckle's comedic timing. The Motion Picture News called it 'a laugh-filled reel that will have audiences in stitches from start to finish,' while Variety noted the 'excellent chemistry between Arbuckle and his supporting cast.' Modern film historians consider it one of the stronger entries in the Arbuckle-Keaton series, particularly noting the effective use of the hospital setting for comic situations. The film is often cited as an example of Arbuckle's skill as both a performer and director, demonstrating his ability to construct elaborate comedic sequences that build to satisfying conclusions.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by audiences in 1918, who appreciated its escapist humor during the difficult final months of World War I. Theater owners reported strong attendance for the film, and it was frequently re-booked for additional runs due to popular demand. Contemporary audience letters to trade publications praised Arbuckle's performance and particularly enjoyed the scenes involving his nurse disguise. The film's success helped solidify Arbuckle's status as one of the most popular comedians of the silent era, with his films consistently drawing large crowds throughout the late 1910s and early 1920s.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Mack Sennett comedies

- Charlie Chaplin films

- Max Sennett's Keystone style

This Film Influenced

- The Three Ages (1923)

- The General (1926)

- The Cameraman (1928)

- Hospital comedies of the 1930s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Library of Congress collection and has been restored by various film archives. Prints exist in 16mm and 35mm formats, and it has been released on DVD as part of several Arbuckle and Keaton collections. While not in perfect condition due to its age, the film is considered complete and viewable, with some deterioration typical of films from this period.