His Lord's Will

Plot

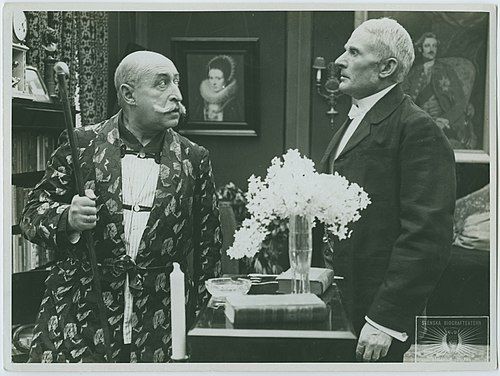

The wealthy Roger Bernhuses de Sars (Karl Mantzius) decides to change his will to leave his entire inheritance to his illegitimate daughter Blenda (Greta Almroth), causing chaos among his family members who had expected to be his heirs. As family members scheme to contest the will and secure their share of the fortune, romantic entanglements develop between the servants and masters, blurring social boundaries. Blenda finds herself caught between her newfound status as an heiress and her humble origins, while the family's servants observe and sometimes participate in the unfolding drama. Fate intervenes through a series of comic misunderstandings and coincidences that ultimately reveal true character and genuine affection versus greed and pretense. The film culminates in a resolution where social hierarchies are questioned and love triumphs over material inheritance, making a subtle commentary on class distinctions in early 20th century Sweden.

About the Production

This film was part of Victor Sjöström's prolific 1919 output, during which he directed multiple films showcasing his versatility across genres. The production utilized the sophisticated studio facilities that Svenska Biografteatern had developed, allowing for elaborate sets that depicted both aristocratic mansions and servants' quarters. The film's exploration of class dynamics required detailed production design to visually represent the social stratification central to the story.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1919, immediately following World War I, during a period of significant social upheaval across Europe. Sweden, though neutral during the war, experienced its own social transformations, including growing questions about traditional class structures and the role of inheritance in maintaining social hierarchies. The golden age of Swedish cinema (1917-1924) was characterized by artistic innovation and international recognition, with directors like Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller gaining worldwide acclaim. This period saw Swedish films competing successfully with Hollywood productions in international markets. The film's exploration of illegitimacy and inheritance rights reflected contemporary legal and social debates about family structures and property rights. The post-war period also saw the rise of middle-class values and questioning of aristocratic privilege, themes that resonate throughout the film's narrative.

Why This Film Matters

His Lord's Will holds particular importance in film history as one of the earliest cinematic explorations of class dynamics and master-servant relationships, predating more famous works on similar themes. The film represents a crucial example of Victor Sjöström's versatility as a director, demonstrating that he could excel in comedy as well as the dramatic works for which he is better known. Its sophisticated approach to social satire influenced later developments in European cinema, particularly French films of the 1930s that examined class structures. The film is also significant for its contribution to the golden age of Swedish cinema, helping establish the international reputation of Swedish filmmaking. Its preservation provides modern audiences with insight into early 20th century Swedish social structures and attitudes toward class, inheritance, and family. The film's blend of comedy with social commentary paved the way for more complex approaches to genre filmmaking in European cinema.

Making Of

Victor Sjöström approached this comedy with the same artistic seriousness he brought to his dramatic works, using the genre to explore social themes rather than merely for laughs. The casting of Karl Mantzius as the patriarch was significant, as he was a renowned stage actor known for his commanding presence. Greta Almroth's performance as Blenda required her to navigate complex social transitions, from illegitimate daughter to potential heiress. The film's production benefited from Svenska Biografteatern's sophisticated studio system, which by 1919 had developed advanced techniques for lighting and set design. Sjöström worked closely with cinematographer Julius Jaenzon to create visual distinctions between the world of the masters and servants, using lighting and composition to reinforce the social commentary. The director's background in both theater and film allowed him to extract nuanced performances that balanced comedy with social observation.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Julius Jaenzon employed sophisticated lighting techniques to distinguish between the worlds of masters and servants, using softer, more diffused lighting for aristocratic spaces and harsher illumination for servants' quarters. The film utilized the advanced studio facilities of Svenska Biografteatern to create visually rich compositions that reinforced the social commentary. Jaenzon, who was Sjöström's regular collaborator, employed camera angles and movements that subtly emphasized power dynamics between characters. The visual style balanced the requirements of comedy with the serious social themes, using framing and composition to highlight both humorous situations and social commentary. The film's cinematography demonstrated the technical sophistication that had made Swedish cinema internationally respected during this period.

Innovations

The film demonstrated the technical sophistication of Swedish cinema during its golden age, particularly in its use of lighting and set design to reinforce social commentary. The production employed advanced studio techniques that allowed for elaborate sets depicting both aristocratic and servant environments. The film's editing showed considerable sophistication in its timing of comic moments and dramatic revelations. The technical quality of the cinematography and production design helped establish the international reputation of Swedish filmmaking during this period. The film's preservation demonstrates the relatively high quality of Swedish film stock and processing techniques of the era.

Music

As a silent film, His Lord's Will would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical Swedish cinema of 1919 would have employed either a piano accompanist or small orchestra to provide musical underscoring. The score would have followed contemporary practices of using popular classical pieces and specially composed music to enhance emotional moments and comic timing. Unfortunately, no specific information about the original musical accompaniment for this particular film has survived. Modern screenings of restored versions typically feature newly composed scores that attempt to capture the film's blend of comedy and social commentary.

Famous Quotes

No specific dialogue quotes have survived from this silent film, as intertitles from Swedish films of this era are not well documented in English translation

Memorable Scenes

- The scene where the will is read and family members' reactions reveal their true characters; The comic confrontation between servants and masters when the inheritance plans are revealed; The romantic subplot development between Blenda and her suitor, highlighting class barriers; The final resolution where social hierarchies are questioned and reevaluated

Did You Know?

- This film represents a rare comedic work by Victor Sjöström, who was primarily known for his dramatic masterpieces like 'The Outlaw' and 'The Phantom Chariot'

- The film's exploration of master-servant relationships predates and possibly influenced later French masters like Jean Renoir's 'The Rules of the Game' (1939)

- Greta Almroth, who plays the illegitimate daughter Blenda, was one of Sweden's most popular silent film actresses of the 1910s and early 1920s

- The film was released during what is considered the golden age of Swedish cinema (1917-1924), when Swedish films gained international recognition for their artistic quality

- Victor Sjöström not only directed but also occasionally acted in films during this period, though he does not appear in this particular work

- The film's sophisticated approach to comedy has been compared to the works of Erich von Stroheim and Ernst Lubitsch, who were also exploring social satire in their films

- The original Swedish title 'Hans nåds testamente' literally translates to 'His Grace's Testament', reflecting the aristocratic setting

- This film was one of several Sjöström works from 1919 that showcased his range as a director, moving between genres with remarkable facility

- The film's preservation status makes it particularly valuable for understanding Sjöström's complete artistic vision beyond his more famous dramatic works

What Critics Said

Contemporary Swedish critics praised the film for its sophisticated humor and social insight, noting Sjöström's ability to handle comedy with the same artistic depth he brought to his dramatic works. Critics particularly appreciated the film's nuanced approach to class dynamics, which avoided simplistic caricatures in favor of more complex characterizations. International critics, when the film was exported, noted the distinctive Swedish approach to comedy, which differed from both American and European comic traditions. Modern film historians and critics have reevaluated the film as an important example of early social satire in cinema, with particular attention paid to its influence on later European films dealing with similar themes. The film is often cited in scholarly works about Sjöström's complete oeuvre, demonstrating that his artistic vision encompassed more than just the dramatic masterpieces for which he is primarily remembered.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary Swedish audiences responded positively to the film's humor and social commentary, finding resonance in its portrayal of familiar class dynamics. The film's domestic success contributed to the continued popularity of its stars, particularly Greta Almroth, who was already a beloved figure in Swedish cinema. The comedy's sophisticated approach to social issues appealed to educated urban audiences who were increasingly questioning traditional social hierarchies in the post-war period. International audiences, particularly in countries where Swedish films were distributed, found the film's distinctive Nordic perspective on class and family refreshing compared to more conventional Hollywood comedies of the era. Modern audiences who have had the opportunity to see restored versions of the film often express surprise at its contemporary relevance and sophisticated approach to social themes.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Swedish literary traditions of social commentary

- European theatrical comedy traditions

- The social satire of August Strindberg's works

- Contemporary Swedish stage comedy

- Early American film comedy techniques

This Film Influenced

- Jean Renoir's 'The Rules of the Game' (1939)

- Sacha Guitry's social comedies of the 1930s

- Later Swedish films exploring class dynamics

- European social satires of the 1920s and 1930s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Swedish Film Institute's archives, though like many films from this era, it may exist in incomplete or deteriorated condition. Restoration efforts have been undertaken to preserve this important example of Sjöström's work and Swedish cinema's golden age. The film's survival is particularly valuable given its status as one of Sjöström's rare comedies and its early exploration of social themes that would become more common in later European cinema.