Judex

"Le justicier mystérieux qui frappe où le crime a semé le trouble"

Plot

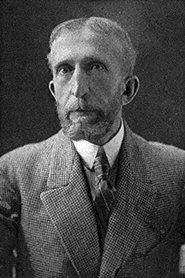

Judex tells the story of a mysterious vigilante who adopts the identity of 'Judex' (Latin for 'judge') to seek justice against corrupt banker Favraux, who has ruined countless families through his fraudulent schemes. When Favraux refuses to repay his debts and plans to marry his daughter Jacqueline to a wealthy aristocrat, Judex intervenes by kidnapping the banker and holding him captive, intending to force him to return his ill-gotten gains to his victims. The plot becomes increasingly complex as Jacqueline, aided by the criminal Diana Monti (played by Musidora), attempts to rescue her father while simultaneously trying to uncover Judex's true identity and motives. Throughout the twelve episodes, Judex employs elaborate disguises, secret passages, and a network of loyal allies to protect the innocent and battle various criminals who also seek Favraux's fortune. The serial culminates in a dramatic revelation of Judex's true identity as Jacques de Trémeuse, a man whose family was destroyed by Favraux's actions, and ultimately delivers justice while restoring order to the corrupted society.

About the Production

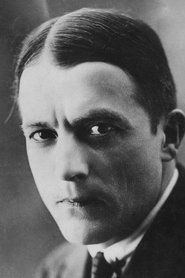

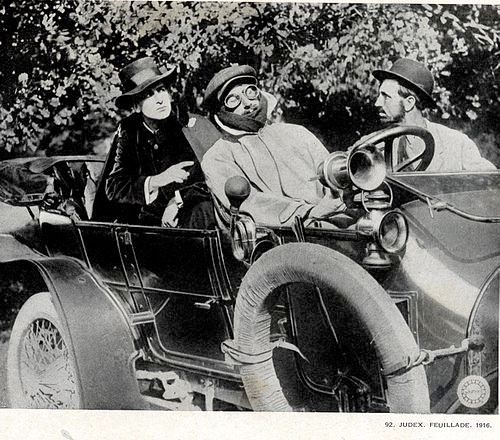

Filmed during World War I, which created significant production challenges including material shortages and crew members being called to military service. Director Louis Feuillade had to work around these constraints while maintaining his signature style. The serial was shot quickly but efficiently, with Feuillade often improvising scenes and using real locations to enhance authenticity. Musidora, who had previously starred in Feuillade's 'Les Vampires,' was pregnant during filming, which required careful scheduling of her scenes. The production utilized innovative techniques for the time, including complex editing for chase sequences and elaborate special effects for Judex's mysterious appearances and disappearances.

Historical Background

Judex was produced during the height of World War I, a period when France was experiencing profound social and economic upheaval. The film's themes of justice against corrupt bankers resonated strongly with audiences who were facing economic hardship and social instability. The serial emerged during the golden age of French cinema, when Gaumont and Pathé dominated the global film market. This period saw the development of the feature-length film and the serial format, with French filmmakers pioneering many narrative and technical techniques. The war had transformed French society, creating a hunger for entertainment that provided escape from the harsh realities of conflict. Judex's vigilante justice appealed to audiences who felt let down by traditional institutions during the war years. The film also reflected contemporary anxieties about modernity and urbanization, with its depiction of Paris as a place where crime could flourish alongside legitimate business. The serial format itself was a response to the cinema's need to create regular returning audiences, similar to how television series would function decades later.

Why This Film Matters

Judex represents a pivotal moment in cinema history as one of the first superhero narratives, predating characters like Superman and Batman by decades. The film established many tropes that would become standard in the superhero genre: the secret identity, the distinctive costume, the network of allies, the mission of justice outside the law, and the rogues' gallery of recurring villains. The character's moral complexity - a hero who operates outside legal boundaries - influenced countless later works. Judex also demonstrated the commercial viability of long-form serialized storytelling, paving the way for future serials in both film and television. The film's success helped establish Gaumont as a major international studio and cemented Louis Feuillade's reputation as a master of the crime serial. Musidora's performance as Diana Monti created one of cinema's first iconic female villains, challenging gender stereotypes of the era. The serial's visual style, with its dramatic use of shadow and location shooting, influenced the development of film noir in subsequent decades. Judex's international success also demonstrated the global appeal of French cinema during this period, helping to establish France as a cultural leader in the emerging art form.

Making Of

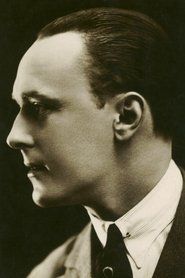

The production of Judex faced numerous challenges due to its timing during World War I. Many of Gaumont's technical staff and actors had been conscripted into military service, forcing Feuillade to work with a reduced crew and sometimes inexperienced personnel. Material shortages meant that sets had to be reused and modified between episodes, and film stock was rationed, requiring careful planning of each shot. Despite these constraints, Feuillade maintained his distinctive visual style, often using natural lighting and location shooting to create a sense of realism. The casting of René Cresté as Judex was particularly significant - Feuillade discovered him while he was recovering from war injuries and felt his haunted appearance perfectly suited the vengeful character. Musidora's involvement was crucial to the film's success; her performance as the seductive villainess Diana Monti created a compelling female antagonist who could match Judex in intelligence and ruthlessness. The serial's complex narrative structure, with its multiple subplots and recurring characters, required meticulous planning, and Feuillade often worked on several episodes simultaneously to maintain continuity.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Judex, credited to Gaumont's team of cameramen including Léonce-Henri Burel, was innovative for its time. The film made extensive use of location shooting in and around Paris, creating a realistic atmosphere that contrasted with the more studio-bound productions of the era. The cinematographers employed natural lighting whenever possible, creating dramatic shadows that enhanced the mystery and suspense of the narrative. The camera work was remarkably mobile for the period, with tracking shots used during chase sequences and dynamic angles that heightened the dramatic impact of key scenes. The film also featured innovative special effects for Judex's appearances and disappearances, using techniques such as multiple exposures and careful editing to create the illusion of the character's supernatural abilities. The visual style emphasized contrast between light and shadow, prefiguring the film noir aesthetic that would emerge decades later. The cinematography also made effective use of Parisian architecture, with the city's buildings, bridges, and underground passages becoming integral elements of the storytelling. The serial's visual language was sophisticated and economical, conveying complex narrative information through carefully composed shots and visual motifs.

Innovations

Judex showcased several technical innovations that were ahead of their time. The serial featured complex editing techniques, particularly in its action sequences and chase scenes, which created a sense of movement and excitement that was rare in films of this period. The production made extensive use of location shooting, which was logistically challenging during wartime but resulted in greater visual authenticity. The film's special effects, while simple by modern standards, were innovative for 1916, including techniques for making Judex appear and disappear mysteriously. The serial also demonstrated advanced narrative techniques for its era, with its complex plotting across twelve episodes requiring careful continuity and sophisticated storytelling. The production design, particularly the creation of Judex's secret headquarters and various disguises, showed remarkable creativity within the constraints of wartime resources. The film's pacing and structure influenced the development of the serial format, with its balance of action, mystery, and character development setting a template for future serial productions. The technical achievements of Judex were particularly impressive given the constraints of wartime production, demonstrating the ingenuity of Feuillade and his crew.

Music

As a silent film, Judex was originally accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The score would have varied by venue, with larger cinemas employing full orchestras while smaller theaters used pianists or small ensembles. The music was typically drawn from classical repertoire and popular songs of the era, with selections chosen to match the mood of each scene. Gaumont likely provided musical suggestions for exhibitors, as was common practice for major productions. In modern restorations, Judex has been accompanied by newly composed scores that attempt to capture the spirit of the original era while utilizing contemporary musical sensibilities. These modern scores often emphasize the film's suspenseful and dramatic elements, using leitmotifs for different characters and themes. The original musical experience would have included sound effects created by theater musicians and effects specialists, adding to the immersive quality of the serial. The absence of recorded dialogue meant that the visual storytelling had to be exceptionally clear, a challenge that Feuillade and his team met through careful staging and expressive performances.

Famous Quotes

Je suis Judex, le justicier de l'ombre.

I am Judex, the avenger from the shadows.)

La justice est aveugle, mais elle a des bras.

Justice is blind, but it has arms.)

Quand la loi faillit, un autre jugement s'impose.

When the law fails, another judgment becomes necessary.)

Mon masque cache mon visage, mais pas ma conscience.

My mask hides my face, but not my conscience.)

Le crime paie toujours, mais avec des intérêts.

Crime always pays, but with interest.)

Memorable Scenes

- Judex's first appearance at Favraux's party, where he dramatically appears from behind a curtain to deliver his judgment

- The elaborate kidnapping sequence where Judex's team abducts the banker from his heavily guarded estate

- Diana Monti's seductive dance at the masquerade ball, where she attempts to uncover Judex's identity

- The climactic reveal of Judex's secret headquarters beneath the Parisian streets

- The final confrontation where Judex removes his mask to reveal his true identity to Jacqueline

- The thrilling chase through the Paris catacombs, with Judex pursuing Diana Monti

- The scene where Judex uses his network of allies to simultaneously expose multiple corrupt officials

- The emotional reunion between Judex and his long-lost mother, revealing his tragic backstory

Did You Know?

- The character of Judex was created as a heroic counterpoint to the criminal protagonists of Feuillade's earlier successful serial 'Les Vampires'

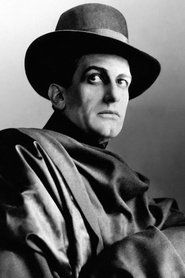

- René Cresté, who played Judex, was a former soldier who had been wounded in World War I before being cast in the title role

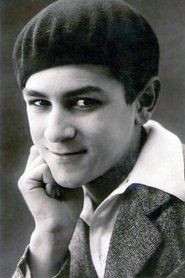

- Musidora, who played the villainess Diana Monti, was one of the first true sex symbols of cinema and was famous for her distinctive black bob haircut

- The serial was originally conceived as a response to public criticism that Feuillade's previous works glorified crime

- Judex's costume, including the distinctive cloak and hat, influenced later superhero designs, particularly Batman

- The film was shot on location in and around Paris, giving it an authentic atmosphere that contrasted with the more studio-bound productions of the era

- Feuillade wrote the entire screenplay himself, drawing inspiration from both contemporary crime stories and medieval tales of justice

- The serial was so popular that it spawned two sequels: 'La Nouvelle Mission de Judex' (1917-1918) and 'Judex versus Roosevelt' (1919)

- The character's name 'Judex' was deliberately chosen to be simple and memorable, similar to 'Fantômas' from Feuillade's earlier work

- Despite being made during wartime, the serial avoided direct references to the conflict, instead focusing on its crime and revenge narrative

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Judex as a masterful blend of suspense, action, and moral drama. French newspapers of the era hailed it as 'a triumph of French cinema' and praised Feuillade's direction for creating 'unparalleled tension and excitement.' Critics particularly noted the film's sophisticated narrative structure and the strong performances of the cast, especially René Cresté's portrayal of the enigmatic hero. Some reviewers commented on the film's moral message, seeing it as a positive alternative to the criminal protagonists of Feuillade's earlier works. In the decades following its release, Judex was reassessed by film historians and critics, who recognized its influence on subsequent cinema. The French New Wave directors of the 1950s and 1960s, particularly François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, cited Feuillade's work as an influence on their own films. Modern critics have praised Judex for its innovative visual style, complex plotting, and its role in developing the language of cinema. The serial is now regarded as a masterpiece of early cinema and a crucial work in the development of the crime and superhero genres.

What Audiences Thought

Judex was enormously popular with audiences both in France and internationally. The serial created a sensation when it was released, with crowds gathering outside cinemas for each new episode. French audiences were particularly drawn to the character of Judex, seeing him as a hero who delivered justice in a time of social upheaval and war. The serial's success led to merchandise, including Judex masks and toys, demonstrating the character's cultural impact. International audiences also embraced the film, with successful releases in countries including the United States, Britain, and Italy. The serial's cliffhanger endings created anticipation for each subsequent episode, a technique that would become standard in serial storytelling. Audience reaction was so positive that Gaumont quickly commissioned sequels, recognizing the commercial potential of the character. The film's popularity endured long after its initial release, with revivals in theaters throughout the 1920s and later appreciation in film societies and archives. Modern audiences rediscovering Judex through restorations and screenings continue to be impressed by its sophisticated storytelling and visual inventiveness.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Les Vampires (1915) - Feuillade's own previous work

- Fantômas (1913-1914) - another Feuillade serial

- The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

- Victor Hugo's Les Misérables

- Edgar Allan Poe's mystery stories

- Contemporary French crime fiction and newspapers

- Medieval tales of justice and chivalry

- Theatrical melodrama traditions

This Film Influenced

- The Batman comics and films

- The Shadow (1930s radio and film)

- Zorro films and series

- The Dark Knight (2008)

- V for Vendetta (2006)

- The Phantom (1996)

- The Spirit (2008)

- Watchmen (2009)

- The Punisher films

- Daredevil comics and series

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Judex has been remarkably well-preserved for a film of its age. Most of the original twelve episodes survive in various archives, particularly at the Cinémathèque Française. The film has undergone several restorations, with the most comprehensive being a 1999 restoration by Gaumont and the Cinémathèque Française, which used elements from multiple sources to create the most complete version possible. Some minor gaps and damaged sections remain, but the narrative is essentially complete. The restoration work has preserved the film's visual quality and allowed modern audiences to experience Feuillade's masterwork as intended. The film is considered one of the best-preserved major works from the French silent era, thanks to its initial popularity and the efforts of film preservationists who recognized its historical importance early on.