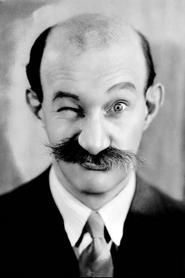

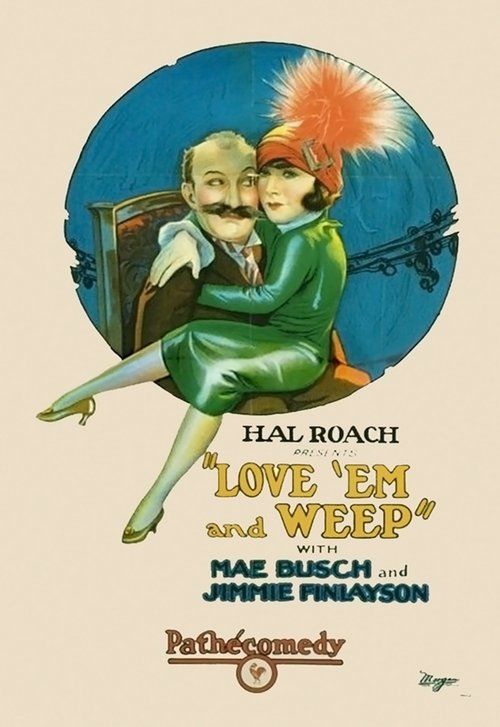

Love 'Em and Weep

Plot

Successful businessman Titus Tillsbury (James Finlayson) is enjoying his comfortable life with his wife when his past comes back to haunt him in the form of an old flame, played by Mae Busch, who arrives in town with blackmail on her mind. Desperate to keep his wife from discovering their previous relationship, Titus enlists the help of his friend (Stan Laurel) to act as a decoy and keep the troublesome woman away from his home. What follows is a series of comedic misunderstandings and chaotic situations as the friend tries to intercept the blackmailer while Titus attempts to maintain his domestic tranquility. The situation escalates as more people become involved in the deception, leading to increasingly frantic attempts to preserve the secret. The film culminates in a classic silent comedy finale where all the deception comes crashing down in a hilarious confrontation.

About the Production

This was one of the early collaborations between Stan Laurel and James Finlayson before Laurel's official partnership with Oliver Hardy. The film was shot in just a few days, typical for Roach's rapid production schedule. Mae Busch was a regular at Hal Roach Studios and would later become famous as the frequent foil for Laurel and Hardy. The film was produced during the transition period when Roach was experimenting with different comedy pairings before establishing the legendary Laurel and Hardy team.

Historical Background

1927 was a landmark year in cinema history, marking the transition from silent films to 'talkies' with the release of 'The Jazz Singer.' This film was produced just months before that revolutionary change, representing the pinnacle of silent comedy craftsmanship. The Roaring Twenties were in full swing, and American audiences were flocking to movie theaters in record numbers. Comedy shorts were a staple of cinema programming, often shown before feature films. Hal Roach Studios was competing with other comedy powerhouses like Mack Sennett and Buster Keaton for audience attention. The film reflects the social mores of the 1920s, with its emphasis on domestic respectability and the consequences of past indiscretions. The economic prosperity of the period meant that studios could invest more in production values, even for short films.

Why This Film Matters

'Love 'Em and Weep' holds significant importance in film history as a precursor to the Laurel and Hardy comedy team. It demonstrates the evolution of American film comedy from slapstick to more character-driven humor. The film's structure and themes would influence countless later comedies dealing with marital deception and blackmail. Its existence as a blueprint for the later 'Chickens Come Home' makes it a valuable study in how comedy teams refined their material. The film represents the Hal Roach Studios' contribution to developing the American comedy short format that would dominate theaters throughout the late 1920s and 1930s. It also showcases the collaborative development process that created some of cinema's most enduring comedy characters.

Making Of

The production of 'Love 'Em and Weep' took place during a pivotal period at Hal Roach Studios when the comedy unit was experimenting with different star combinations. Stan Laurel had been working as a solo comedian and supporting player, while James Finlayson was establishing himself as a reliable comic character actor. The film was directed by Fred Guiol, who was instrumental in developing the studio's comedy style and would later direct many of Laurel and Hardy's most famous shorts. Mae Busch was already a veteran comedian by this time, having worked with Charlie Chaplin and other comedy greats. The filming followed the efficient Hal Roach method of shooting quickly with minimal takes, relying on the performers' timing and improvisation skills. The set design was typical of Roach productions - realistic middle-class interiors that provided plenty of opportunities for physical comedy and door-slamming farce.

Visual Style

The cinematography, typical of Hal Roach productions of the era, was straightforward and functional, designed to clearly showcase the comedic action. The camera work employed medium shots for dialogue scenes and wider shots for physical comedy sequences. The lighting was bright and even, characteristic of comedy films of the period that needed to clearly capture performers' expressions and movements. The film used the standard 1.33:1 aspect ratio of silent films. The cinematographer focused on maintaining visual clarity during the chaotic scenes, ensuring that the multiple characters and their interactions remained visible and comprehensible to the audience.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical terms, the film demonstrated the polished production techniques that Hal Roach Studios had perfected by 1927. The editing was crisp and well-paced, crucial for maintaining comedic rhythm in silent films. The film made effective use of intertitles to advance the plot without disrupting the flow of action. The set design allowed for smooth camera movement and multiple entrances/exits essential for farcical comedy. The film showcased the studio's ability to produce high-quality shorts efficiently, a technical and organizational achievement that helped Roach dominate the comedy short market.

Music

As a silent film, 'Love 'Em and Weep' had no synchronized soundtrack. The original theatrical presentation would have been accompanied by live music, typically a piano or small theater orchestra. The musical score would have been compiled from standard photoplay music libraries, with selections chosen to match the mood of each scene - upbeat and frantic for the comedy sequences, more romantic or tense for the dramatic moments. Some theaters might have used cue sheets provided by the studio suggesting appropriate musical pieces. The music would have emphasized the comedic timing and helped guide audience emotional responses throughout the film.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles and pantomime rather than spoken quotes

Memorable Scenes

- The frantic opening sequence where Titus Tillsbury receives the threatening letter from his old flame, establishing the blackmail premise. The scene where Stan Laurel's character attempts to intercept Mae Busch before she can reach the Tillsbury home, featuring classic physical comedy and near-misses. The climactic confrontation scene where all the characters converge in the Tillsbury household, leading to chaotic revelations and comedic confusion. The final resolution where the truth comes out in a series of misunderstandings that ultimately resolve in favor of the protagonists.

Did You Know?

- This film was later remade in 1931 as 'Chickens Come Home' with Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, making it one of the few Laurel and Hardy films that had a previous version with Laurel in a different role

- James Finlayson plays the lead role here, but in the 1931 remake, Oliver Hardy took over the part while Laurel retained his supporting character

- The film represents an early example of the 'domestic comedy' formula that would become a staple of Laurel and Hardy's work

- Mae Busch, who plays the blackmailing old flame, would become one of the most frequent female antagonists in Laurel and Hardy films

- Director Fred Guiol was a key figure at Hal Roach Studios and would go on to direct many classic Laurel and Hardy shorts

- The film showcases Stan Laurel's early comedic style before his character was fully developed for the Laurel and Hardy partnership

- This was one of the last films Stan Laurel made before his official teaming with Oliver Hardy, which began later in 1927

- The blackmail plot was a common trope in silent comedies, allowing for misunderstandings and frantic deception scenarios

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in trade publications like Variety and The Moving Picture World praised the film's comedic timing and performances. Critics noted James Finlayson's increasingly refined comic technique and Stan Laurel's growing screen presence. The film was considered a solid example of Roach's comedy output, with reviewers highlighting the effective use of domestic settings for farcical situations. Modern film historians and comedy scholars recognize the film as an important stepping stone in the development of Laurel and Hardy's comedy style. The film is often cited in studies of silent comedy as an example of the transition from pure slapstick to character-based humor that would define the sound era.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1927 responded positively to the film's relatable domestic situation and escalating comedy. The blackmail premise, while serious in nature, was treated with the light touch that moviegoers expected from comedy shorts. Theater owners reported good audience reactions with consistent laughter throughout the film's runtime. The chemistry between the performers, particularly the contrast between Finlayson's flustered businessman and Laurel's helpful friend, resonated with viewers. The film's success in theaters contributed to Hal Roach's decision to continue experimenting with different comedy pairings, eventually leading to the official Laurel and Hardy team.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier domestic comedies from Mack Sennett Studios

- French farce traditions

- American vaudeville comedy routines

- Previous Hal Roach comedy shorts

This Film Influenced

- Chickens Come Home (1931) - direct remake with Laurel and Hardy

- Other Laurel and Hardy domestic comedy shorts

- Later comedy films dealing with blackmail and deception

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in complete form and has been preserved by film archives. 16mm and 35mm copies exist in various film collections, including the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. The film has been digitally restored for home video releases and is considered to be in good preservation condition for a film of its age. Some deterioration is evident in existing prints, but the film remains viewable and complete.