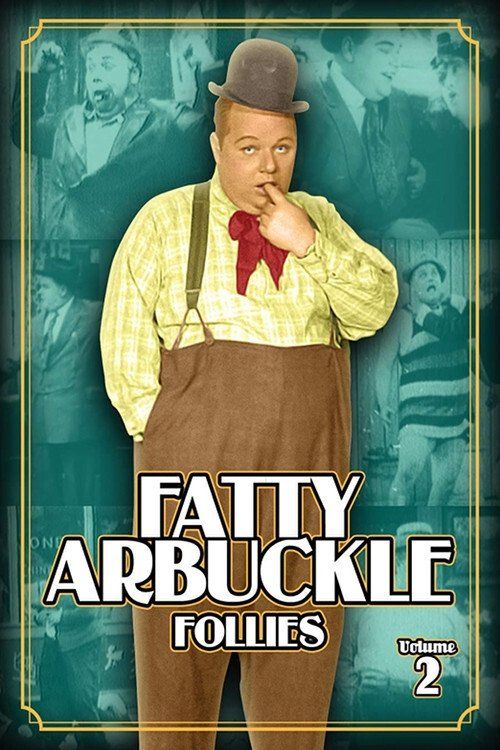

Mabel and Fatty’s Married Life

Plot

In this Keystone comedy, Mabel's husband Fatty leaves town on business, leaving her alone in their home. As night falls, Mabel becomes increasingly frightened when she begins hearing strange noises and seeing mysterious shadows moving through the house. Her anxiety reaches a fever pitch when she believes gangsters have broken in, leading to a series of frantic attempts to protect herself and call for help. In a classic comedic twist, it's revealed that Fatty returned early and was simply trying to surprise his wife, inadvertently causing all the terror through his clumsy attempts to be stealthy. The film culminates in a chaotic but heartwarming reunion between the flustered couple.

About the Production

This film was part of the highly successful Mabel and Fatty series that capitalized on the chemistry between Arbuckle and Normand. The production followed Keystone's typical rapid shooting schedule, often completing these one-reel comedies in just 1-2 days. The film showcases Arbuckle's signature physical comedy style and Normand's expressive acting abilities.

Historical Background

1915 was a pivotal year in American cinema, occurring during the transition from short films to feature-length productions. World War I was raging in Europe, making American films, particularly comedies, increasingly important as escapist entertainment. The film industry was rapidly consolidating in Hollywood, with Keystone Studios being one of the most prolific producers. This period also saw the rise of movie stars as cultural icons, with Arbuckle and Normand being among the first generation of film celebrities. The technical aspects of filmmaking were evolving quickly, with better lighting and camera movement becoming more common, even in short comedies.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important example of the domestic comedy genre that helped establish the romantic comedy format in American cinema. The Arbuckle-Normand partnership demonstrated early examples of gender equality in comedy, with Normand often driving the narrative and Arbuckle playing the bumbling but lovable husband. The film's success contributed to the establishment of comedy as a commercially viable genre and helped cement the template for the 'screwball comedy' that would dominate the 1930s. It also represents a rare example of a female star (Normand) having equal billing and creative input with her male counterpart during an era when women's roles in film were typically limited to being objects of desire.

Making Of

The production of 'Mabel and Fatty's Married Life' exemplified the Keystone Studios method of rapid, efficient filmmaking. Arbuckle and Normand had developed such a strong working relationship that they could often improvise entire scenes, with Arbuckle directing while performing. The film's simple domestic setting allowed the crew to focus on the physical comedy and timing rather than elaborate sets. Contemporary accounts suggest that much of the film's humor was developed on set, with the cast and crew contributing gags throughout the shooting process. The collaborative atmosphere at Keystone meant that even minor crew members might suggest bits that ended up in the final film.

Visual Style

The cinematography by unknown Keystone cameramen follows the typical style of the period, with static camera positions and medium shots that allow full appreciation of the physical comedy. The lighting is naturalistic for the interior scenes, using the available light from the set windows supplemented by arc lights. The camera work is functional rather than artistic, designed primarily to capture the action clearly for the audience. The film does feature some effective use of shadows to create the mysterious atmosphere that drives the plot.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking technically, the film demonstrates the efficient production methods that made Keystone Studios successful. The use of a single domestic set allowed for economical filming while providing enough variety for the comedic action. The film's editing, though basic by modern standards, effectively builds tension and releases it through comedic timing. The makeup and costume design effectively establish the characters' personalities and social status within the constraints of the budget.

Music

As a silent film, 'Mabel and Fatty's Married Life' would have been accompanied by live music during its theatrical run. Typical accompaniment would have included a pianist or small orchestra playing popular songs of the era along with classical pieces matched to the on-screen action. The score would have been more energetic during the chase sequences and more suspenseful during the mysterious moments. No specific musical score was composed for the film, leaving the musical interpretation to individual theater musicians.

Famous Quotes

(As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles and pantomime rather than spoken quotes)

Memorable Scenes

- The sequence where Mabel barricades herself in the bedroom, using furniture and household items to create elaborate defenses against the supposed intruders

- Fatty's clumsy attempts to sneak around his own house, accidentally creating increasingly suspicious noises

- The final reveal where both characters realize their mutual misunderstanding, leading to a tender reconciliation

Did You Know?

- This was one of over a dozen films that Roscoe Arbuckle and Mabel Normand made together between 1913-1915

- The film was directed by Arbuckle himself, showcasing his dual talent as both performer and filmmaker

- Keystone Studios typically produced these short comedies at a rate of one per week, making them incredibly efficient productions

- The 'haunted house' premise was a popular trope in early comedy, allowing for maximum physical gags and expressive acting

- Mabel Normand was one of the few women in early Hollywood with significant creative control, often co-directing and writing her films

- The film's success helped establish Arbuckle as one of the highest-paid actors in Hollywood by 1918

- Dan Albert, who appears in the cast, was a regular Keystone player who often played supporting roles in Arbuckle films

- The film was released during the height of the 'Keystone Cops' era, when slapstick comedy dominated American cinema

- Arbuckle's character 'Fatty' became one of the most recognizable comedy personas of the 1910s

- The film's preservation is remarkable, as many Keystone shorts from this period have been lost

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews praised the film for its inventive gags and the undeniable chemistry between its stars. The Moving Picture World noted that 'Arbuckle and Normand continue to delight audiences with their domestic misunderstandings and physical comedy.' Modern critics view the film as an excellent example of early American slapstick, with particular appreciation for Normand's expressive performance and Arbuckle's timing. Film historians often cite this work as representative of the Keystone style at its peak, before the studio's decline in the late 1910s.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by contemporary audiences, who had come to expect quality entertainment from the Arbuckle-Normand pairing. Theater owners reported strong attendance for the short, often programming it as part of a comedy-heavy bill. Audiences particularly enjoyed the relatable domestic setting combined with the escalating absurdity of the situation. The film's success led to increased demand for more Mabel and Fatty collaborations, cementing their status as one of the most popular comedy teams of the mid-1910s.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Keystone comedies

- Mack Sennett's comedic style

- French and Italian slapstick traditions

- Stage farce traditions

This Film Influenced

- Later domestic comedies

- The Three Stooges shorts

- Abbott and Costello films

- Modern romantic comedies

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Library of Congress collection and has been restored by various film archives. Prints exist in 16mm and 35mm formats, and it has been made available on home video through several public domain collections. The preservation quality is generally good for a film of this era, though some deterioration is evident in surviving prints.