Mare Nostrum

"A Romance of the War-Torn Seas"

Plot

Mare Nostrum (1926) tells the story of Freya Talberg, a German spy operating in Marseille during World War I who works as a nurse on a hospital ship. She falls in love with Captain Ulysses Ferragut, a Spanish merchant marine captain who commands the ship Mare Nostrum. Despite her growing feelings for Ferragut, Freya continues her espionage activities, ultimately leading to a tragic conflict between her duty to Germany and her love for the captain. The film culminates in Freya's self-sacrifice as she allows herself to be captured and executed to protect both her country and the man she loves, embodying the themes of patriotism and tragic romance that defined many silent era dramas.

About the Production

Director Rex Ingram insisted on authentic maritime sequences, actually filming on the Mediterranean Sea. The production faced significant challenges including dangerous weather conditions at sea and the logistical difficulties of coordinating large-scale naval battle scenes. Ingram's meticulous attention to detail extended to the period costumes and military uniforms, which were historically accurate for the World War I setting.

Historical Background

Mare Nostrum was produced during a fascinating transitional period in cinema history, coming just a year before the release of The Jazz Singer (1927) would revolutionize the industry with sound. The film reflected the ongoing cultural processing of World War I, which had ended only eight years earlier. Many films of this period still romanticized the war experience, though Mare Nostrum contains more complex anti-war sentiments beneath its romantic exterior. The mid-1920s also saw American studios increasingly looking to European literature for source material, with Vicente Blasco Ibáñez being particularly popular. The film's production coincided with the peak of Rex Ingram's career, before his move to Europe and eventual decline in Hollywood influence.

Why This Film Matters

Mare Nostrum represents the pinnacle of the silent epic genre, showcasing the artistic heights that could be achieved without dialogue. The film's sophisticated visual storytelling and complex moral themes demonstrated the maturity of cinema as an art form by the mid-1920s. Its treatment of a female spy as a complex, sympathetic character was somewhat progressive for the time, offering a nuanced portrayal of patriotism versus personal morality. The film's international scope and European setting reflected Hollywood's growing global ambitions and the increasing sophistication of American productions. Though overshadowed by later sound epics, Mare Nostrum influenced subsequent maritime films and war dramas through its technical innovations in filming at sea.

Making Of

Rex Ingram, known for his perfectionism and artistic vision, spent months preparing for this maritime epic. He insisted on filming actual ocean sequences rather than relying on studio tanks, leading to a production that was both ambitious and dangerous. The cast and crew spent weeks aboard ships in the Mediterranean, often working in challenging weather conditions. Alice Terry, playing the German spy Freya, had to perform her own stunts in several scenes, including dramatic sequences on the ship's rigging. Ingram's collaboration with cinematographer John F. Seitz resulted in some of the most sophisticated visual effects of the silent era, particularly in the naval battle sequences that combined full-scale ships with expertly crafted miniatures. The production was also notable for its international cast and crew, reflecting the film's pan-European setting.

Visual Style

John F. Seitz's cinematography in Mare Nostrum was groundbreaking for its time, particularly in the maritime sequences. The film features stunning location photography on the Mediterranean Sea, with dramatic shots of ships battling stormy weather and engaging in naval warfare. Seitz employed innovative techniques including multiple camera setups on moving vessels and the use of filters to enhance the ocean's dramatic appearance. The battle sequences skillfully combined full-scale photography with miniature effects, creating seamless and convincing action scenes. The interior lighting, particularly in the hospital ship scenes, demonstrates the sophisticated use of natural and artificial light that characterized late silent era cinematography.

Innovations

Mare Nostrum was technically innovative for its time, particularly in its approach to filming maritime sequences. The production team developed new techniques for mounting cameras on moving ships, allowing for dynamic shots that had rarely been achieved before. The miniature effects work for the naval battles was considered state-of-the-art, with detailed ship models and sophisticated pyrotechnic effects. The film also featured advanced matte painting techniques for creating the illusion of expansive ocean vistas. Ingram's use of deep focus photography in certain scenes was ahead of its time, creating more visually complex compositions than typical of the era.

Music

As a silent film, Mare Nostrum would have been accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. The original score was composed by William Axt and David Mendoza, who created a sweeping orchestral composition that emphasized the film's romantic and dramatic elements. The score featured leitmotifs for the main characters and incorporated martial themes for the war sequences. For the European releases, local musicians often adapted the score to include regional musical elements. Modern screenings of restored versions typically feature newly commissioned scores that attempt to capture the spirit of the original while utilizing contemporary orchestral arrangements.

Famous Quotes

'Our sea... and our destiny' (opening title card)

'In war, love is the first casualty' (intertitle)

'I serve my country, but my heart serves you' (Freya's declaration)

'The Mediterranean claims her own, in love and in death' (closing title card)

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic naval battle sequence where miniature ships and full-scale vessels create a convincing wartime engagement

- Freya's emotional farewell scene on the ship's deck as she accepts her fate

- The storm sequence where the Mare Nostrum battles Mediterranean waters, showcasing innovative camera work

- The hospital ship scenes highlighting the human cost of war with authentic period details

- The final execution scene, powerfully conveyed through silent acting and visual composition

Did You Know?

- The film is based on the 1918 novel of the same name by Spanish author Vicente Blasco Ibáñez, who also wrote 'The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse'

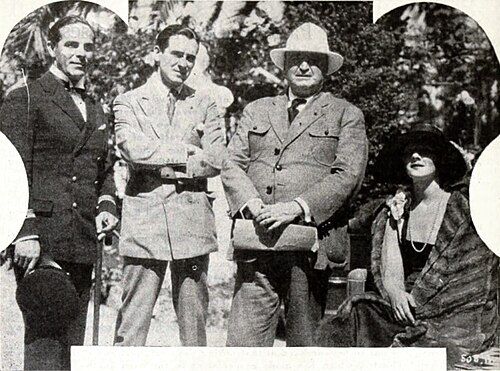

- Director Rex Ingram was married to his leading lady Alice Terry, who played Freya Talberg, marking their fifth collaboration together

- The title 'Mare Nostrum' is Latin for 'Our Sea,' referring to how the Romans called the Mediterranean Sea

- The film featured groundbreaking miniature work for the naval battle sequences, considered highly advanced for 1926

- Despite being an American production, most of the film was shot on location in Europe, unusual for the time

- The film's original running time was approximately 140 minutes, but it was cut for various releases

- MGM promoted the film heavily as an epic romance, though it contains significant anti-war undertones

- The ship used for filming was an actual merchant vessel that had served during World War I

- The film was one of the last major silent epics before the transition to sound began in earnest

- Contemporary critics praised the film's visual scope but some found the romantic elements melodramatic

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Mare Nostrum for its spectacular visual sequences and Ingram's directorial skill. The New York Times called it 'a magnificent achievement in silent cinema' while Variety noted its 'breathtaking maritime photography.' However, some critics found the romantic elements overly sentimental, a common criticism of Ingram's work. Modern critics and film historians have reassessed the film more favorably, recognizing its technical achievements and complex thematic undertones. The film is now regarded as one of Ingram's most accomplished works, though it remains less well-known than his earlier masterpiece The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception was generally positive, with the film performing well in major cities. The romantic storyline between Alice Terry and Antonio Moreno resonated with audiences of the time, though some found the pacing slow by modern standards. The spectacular naval sequences were particularly popular with moviegoers. However, the film's release came just before the sound revolution, and like many late silent epics, it was quickly overshadowed by the new technology. Today, the film is primarily seen by silent film enthusiasts and cinema historians, though those who discover it often praise its visual beauty and emotional depth.

Awards & Recognition

- Photoplay Medal of Honor (1926) - Winner

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) - also based on Blasco Ibáñez

- The Arab (1924) - previous Rex Ingram film

- War Bride (1925) - similar wartime romance themes

- The Big Parade (1925) - contemporary WWI film

This Film Influenced

- Morocco (1930) - similar exotic romance themes

- Casablanca (1942) - wartime romance with moral complexity

- The African Queen (1951) - maritime adventure romance

- Das Boot (1981) - submarine warfare elements

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Mare Nostrum survives in complete form, though some scenes remain lost or incomplete. The film has been preserved by the Museum of Modern Art and the Library of Congress. A restored version was released in the 1990s, combining elements from various prints to create the most complete version available. The restoration work revealed the film's impressive visual quality, particularly in the maritime sequences. Some original tinting has been preserved, adding to the film's visual impact. The film occasionally screens at silent film festivals and special cinema events, often with live musical accompaniment.