Max and His Mother-in-Law

"The Honeymoon from Hell - When Mother Comes Along!"

Plot

Max Linder plays a newlywed who is eager to enjoy his Alpine honeymoon with his young bride, but their romantic getaway is constantly interrupted by the presence of his overbearing mother-in-law. The mother-in-law follows the couple everywhere, from their hotel room to outdoor excursions, creating increasingly awkward and hilarious situations as Max tries to find moments alone with his wife. The comedy escalates as Max attempts various schemes to rid himself of his mother-in-law's presence, including hiding, running away, and creating diversions. Despite his best efforts, the persistent mother-in-law always seems to reappear at the most inopportune moments, leading to a series of slapstick mishaps and comedic misunderstandings. The film culminates in a chaotic chase scene through the Alpine landscape, showcasing Max's trademark physical comedy and exasperated reactions.

About the Production

This was one of many Max Linder shorts produced by Pathé during their peak production period. The film utilized studio sets for interior scenes and likely matte paintings or backdrops for the Alpine sequences. The production would have been shot quickly, typically in 1-2 days, following the efficient factory-like production system Pathé had perfected. The Alpine setting was created using painted backdrops and props, as location shooting was expensive and logistically challenging in 1911.

Historical Background

1911 was a pivotal year in cinema history, marking the transition from short novelty films to more sophisticated narrative storytelling. The film industry was consolidating, with Pathé Frères dominating global production and distribution. This period saw the rise of the star system, with Max Linder becoming one of cinema's first true international celebrities. The film reflects the growing middle class in Europe and their concerns about modern marriage, family dynamics, and the tension between traditional values and new freedoms. The Alpine honeymoon setting tapped into the growing popularity of mountain tourism among the wealthy, making the setting both aspirational and recognizable to audiences. The film was produced just before the feature film revolution that would begin with Italian epics like 'Quo Vadis' (1913) and 'Cabiria' (1914), representing the peak of the short comedy format that had dominated early cinema.

Why This Film Matters

'Max and His Mother-in-Law' represents an important milestone in the development of cinematic comedy and the establishment of recurring character-based humor. The film helped establish the family conflict comedy genre that would become a staple in both silent and sound cinema. Max Linder's sophisticated, dapper character provided an alternative to the more slapstick, rough-edged comedy prevalent at the time, influencing the development of the 'gentleman comedian' archetype. The film's international success demonstrated the universal appeal of family-based humor and helped establish the template for romantic comedies featuring interfering relatives. Linder's work, including this film, was particularly influential on American comedy, with Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Buster Keaton all acknowledging his impact. The film also represents the peak of French cinematic dominance before World War I, showcasing the sophisticated visual storytelling and comic timing that made French films popular worldwide.

Making Of

The production of 'Max and His Mother-in-Law' followed the efficient Pathé studio system of the early 1910s. Max Linder, who had significant creative control by this point, likely collaborated closely with director Lucien Nonguet on the gags and scenarios. The film was shot on 35mm film using hand-cranked cameras, requiring precise timing from the actors. The Alpine setting was created using the studio's extensive collection of painted backdrops and props, a common practice that allowed for exotic locations without the expense of location shooting. Linder's physical comedy required multiple takes to perfect the timing of his movements and reactions. The mother-in-law character was played by a male actor in drag, a common practice in early cinema when female actors were unavailable or for comic effect. The film's editing was done by physically cutting and splicing the film negative, with intertitles hand-lettered and photographed separately.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Pathé's studio cameramen utilized the relatively sophisticated techniques available in 1911. The film employed medium shots and close-ups to capture Linder's expressive reactions, a technique that was still relatively innovative at the time. The Alpine sequences likely used matte paintings or painted backdrops combined with forced perspective to create the illusion of mountain landscapes. The camera work was static, as was typical of the era, but careful blocking and movement within the frame created dynamic visual interest. The film may have featured some location photography for establishing shots, blended seamlessly with studio work. Lighting was natural and even, characteristic of Pathé's house style, ensuring clarity for the visual gags. The cinematography supported the comedy by maintaining clear sightlines and allowing audiences to fully appreciate the physical humor and facial expressions that drove the narrative.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical terms, the film demonstrated the sophisticated production techniques Pathé had perfected by 1911. The seamless integration of studio sets with location elements showed the advancing art of film illusion. The film's editing, while simple by modern standards, represented clear narrative continuity that was still developing in cinema. The use of intertitles was minimal and efficient, relying primarily on visual storytelling. The film may have featured some early special effects techniques for the Alpine sequences, such as multiple exposure or matte work. The production quality reflected Pathé's commitment to technical excellence, with consistent exposure and focus throughout. The film also demonstrated the emerging language of cinematic comedy, establishing techniques for timing and visual gag presentation that would influence the medium for decades.

Music

As a silent film, 'Max and His Mother-in-Law' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical screenings. The typical presentation would have featured a pianist or small orchestra playing appropriate mood music and comedic cues. Pathé often provided musical suggestions with their film prints, recommending popular songs of the era or classical pieces that matched the on-screen action. For the Alpine scenes, music might have included folk-inspired melodies or popular waltzes, while the comedy sequences would have been accompanied by jaunty, playful tunes. The rhythm of the live music would have been carefully synchronized with the physical comedy, enhancing the timing and impact of the gags. In larger theaters, sound effects might have been created live using various props and devices, adding another layer to the comedic experience.

Famous Quotes

(Intertitle) 'Max had just married - but his troubles were just beginning!'

(Intertitle) 'A honeymoon for two? Mother thought otherwise!'

(Intertitle) 'In the Alps, even the mountains cannot hide from Mother!'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where Max discovers his mother-in-law has packed her bags for the honeymoon, his face falling from joy to horror in a matter of seconds; The sequence where Max tries to create a romantic moment by the Alpine lake, only to have his mother-in-law appear playing a loud accordion; The climactic chase scene where Max attempts to escape his mother-in-law by skiing down a mountain, with both characters tumbling and sliding in increasingly absurd positions; The hotel corridor scene where Max tries to sneak to his bride's room while avoiding his mother-in-law, using a series of increasingly ridiculous hiding spots and disguises.

Did You Know?

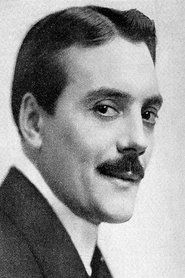

- Max Linder was one of the first international film stars, earning an unprecedented salary of 1 million francs per year at the height of his popularity

- This film was part of a series of over 100 short comedies Linder made for Pathé between 1905 and 1913

- The mother-in-law trope was a recurring theme in early comedy, reflecting changing family dynamics in the early 20th century

- Linder's character 'Max' was one of the first recurring comic characters in cinema history

- The film was likely tinted by hand for theatrical release, as was common with Pathé productions of this era

- Max Linder influenced Charlie Chaplin, who called him 'the professor' and acknowledged learning from his techniques

- The film was distributed internationally, with title cards translated for different markets

- Pathé was the largest film company in the world at the time, with production facilities across Europe and America

- Linder's trademark top hat and cane, featured in this film, became iconic elements of silent comedy

- The film's success led to several sequels featuring similar family conflict themes

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its clever gags and Linder's impeccable comic timing. French trade journals of the era noted the film's 'delicious situations' and 'masterful execution.' International reviewers particularly appreciated the visual comedy that transcended language barriers, making it popular in export markets. Modern film historians view the film as an exemplary example of early narrative comedy, with scholars noting its sophisticated use of continuity editing and character development within the short format. The film is often cited in retrospectives of Linder's work as representing his mature style, where physical comedy was combined with situational humor and character-based jokes. Recent restorations have allowed contemporary critics to appreciate the film's technical achievements and its role in establishing comedy conventions that would dominate cinema for decades.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular with audiences of its time, who were devoted fans of Max Linder's character and eagerly anticipated each new installment in his series. Theater owners reported strong attendance for the film, particularly in urban centers where Linder had a devoted following. The mother-in-law theme resonated with working and middle-class audiences who found humor in the universal family dynamics portrayed. The film's success was evident in its wide international distribution, with documented screenings across Europe, North America, and even in colonial territories. Audience reactions were typically enthusiastic, with reported laughter and applause during theatrical screenings. The film's popularity contributed to Linder's status as one of the highest-paid performers of his era and helped establish the commercial viability of comedy shorts as a programming staple in theaters worldwide.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès' trick films

- French theatrical comedy traditions

- Commedia dell'arte character archetypes

- Pathé's established comedy formulas

- Max Linder's earlier film characters

This Film Influenced

- Charlie Chaplin's 'The Champion' (1915)

- Harold Lloyd's 'From Hand to Mouth' (1919)

- Buster Keaton's 'The Navigator' (1924)

- Early Laurel and Hardy shorts

- Numerous mother-in-law comedies throughout film history

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with some elements surviving in film archives. While not completely lost, some sequences may be missing or damaged. The surviving elements have been restored by film preservation institutions, particularly the Cinémathèque Française and other European archives. The film exists in various versions due to the practice of creating multiple negatives for international distribution. Some restored versions include reconstructed title cards based on original Pathé documentation. The preservation status reflects the typical survival rate of Pathé productions from this period, with approximately 30-40% of Max Linder's films surviving in some form.