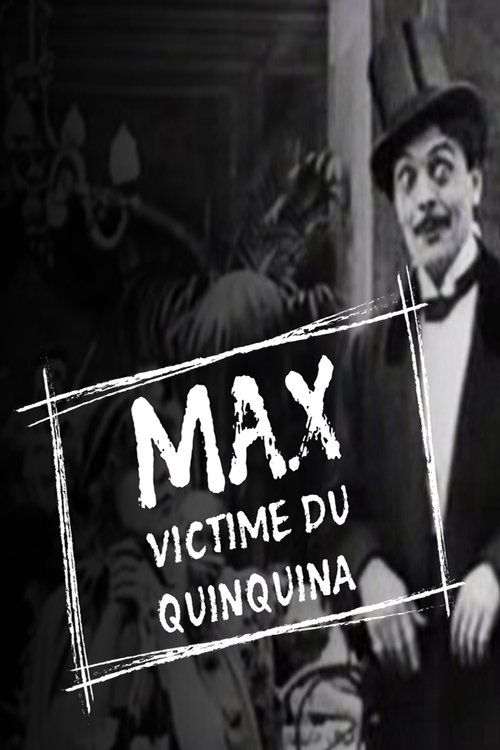

Max Takes Tonics

Plot

In this classic French comedy short, Max visits his doctor complaining of feeling unwell and is prescribed a tonic called Bordeaux of Cinchona to be taken every morning. Upon returning home, Max discovers a large glass on his table labeled 'Souvenir de Bordeaux' left by his wife, mistakenly believing it to be his prescribed medicine. He consumes the entire contents in one go, immediately feeling much better and more energetic than ever before. Unbeknownst to Max, he has actually consumed a full glass of Bordeaux wine, sending him into a state of complete drunkenness. The remainder of the film follows Max's increasingly erratic and hilarious behavior as he stumbles through his day, attempting to maintain his dignity while completely intoxicated. His drunken antics lead to a series of comedic misunderstandings and physical comedy routines that showcase Max Linder's trademark style.

About the Production

This film was produced during the peak of Max Linder's popularity at Pathé, the dominant French film company of the era. The production utilized the standard single-camera setup typical of early cinema, with Linder himself contributing to the gag writing and staging. The film was likely shot in just one or two days, as was common for comedy shorts of this period. The prop work, particularly the medicine bottle and wine glass, was crucial to the film's central misunderstanding gag.

Historical Background

1911 was a pivotal year in cinema history, occurring during the transition from short novelty films to more sophisticated narrative storytelling. The French film industry, led by companies like Pathé and Gaumont, dominated global cinema production. This period saw the emergence of film stars as recognizable personalities, with Max Linder being among the first true international movie celebrities. The film was made just three years before World War I would disrupt European cinema production and shift the center of the film world to Hollywood. The medical theme reflected contemporary interest in health and patent medicines, which were widely marketed and consumed during this era. The sophistication of Linder's comedy represented a maturation of cinematic language, moving beyond simple gag films toward character-driven narratives.

Why This Film Matters

Max Takes Tonics represents an important milestone in the development of screen comedy, showcasing the sophisticated character-based humor that would influence generations of comedians. Linder's portrayal of a gentleman in embarrassing situations created a template for comedy that balanced dignity with absurdity, a formula later perfected by comedians like Buster Keaton and Jacques Tati. The film's use of a simple misunderstanding to generate comedy demonstrates the narrative efficiency that would become standard in comedy filmmaking. Linder's international popularity helped establish the global appeal of comedy as a universal language, transcending cultural and linguistic barriers. This film, along with Linder's other works, proved that screen comedy could be subtle and character-driven rather than purely physical, expanding the artistic possibilities of the medium.

Making Of

The film was created during what many consider the golden age of French cinema, before World War I devastated the European film industry. Max Linder was not only the star but also heavily involved in the creative process, often co-writing and developing his own gags. The production would have taken place on a simple set with minimal lighting equipment, using natural light when possible. Linder's refined, gentlemanly approach to comedy was revolutionary at the time, as most comedy in early cinema relied heavily on broad physical slapstick. The film was likely shot in sequence, as editing capabilities were limited in 1911. Linder's background in theater influenced his precise timing and expressive facial work, which translated well to the silent medium.

Visual Style

The cinematography reflects the technical limitations and aesthetic preferences of 1911 filmmaking. The film was likely shot on 35mm black and white film using a hand-cranked camera, resulting in the slightly variable frame rates common to the era. The camera remains stationary for most shots, using medium shots to capture both Linder's facial expressions and his physical comedy. Lighting would have been primarily natural or simple studio lighting, creating the high-contrast look typical of early cinema. The composition follows the theatrical tradition of keeping the action centered and clearly visible to the audience. Despite these technical limitations, the cinematography effectively serves the comedy by ensuring every gag and reaction is clearly visible to the audience.

Innovations

While not technically innovative in terms of camera work or editing, the film demonstrates the sophisticated narrative construction that was becoming more common in 1911. The effective use of a single prop (the wine glass) to drive the entire plot shows an advanced understanding of cinematic storytelling. The film's pacing and gag structure represent a refinement of comedy film techniques that would influence the genre for decades. Linder's performance technique, combining subtle facial expressions with broader physical comedy, showed new possibilities for screen acting. The film's success in creating humor from a simple misunderstanding demonstrated the narrative efficiency that would become a hallmark of comedy cinema.

Music

As a silent film, 'Max Takes Tonics' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical accompaniment would have been a pianist or small orchestra playing appropriate music to match the on-screen action. For comedy scenes like this, the music would likely have been light and playful, possibly using popular songs of the era or classical pieces adapted for comic effect. During Max's drunken scenes, the music might have become more erratic or whimsical to enhance the humor. Modern screenings of the film are often accompanied by newly composed scores or period-appropriate music that captures the light, comedic tone of the original presentations.

Famous Quotes

(Title card) Doctor: 'You must take Bordeaux of Cinchona every morning'

(Title card) Max: 'I feel wonderful! This medicine is miraculous!'

(Title card) Max: 'I have never felt so energetic in my life!'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where Max visits the doctor and receives his prescription, establishing the premise with Max's characteristic hypochondria. The pivotal moment when Max discovers the 'Souvenir de Bordeaux' glass and confidently drinks the entire contents, believing it to be his medicine. The sequence of Max attempting to go about his day while increasingly intoxicated, including his exaggerated walk and confused expressions. The climax where Max's drunken state becomes apparent to others, leading to social embarrassment and physical comedy moments as he tries to maintain his dignity while completely inebriated.

Did You Know?

- Max Linder was one of the first international comedy stars, predating Charlie Chaplin's fame by several years

- The film's title in French was 'Max et les Toniques' or sometimes listed as 'Max prend des toniques'

- This was one of over 100 short films Linder made between 1905 and 1914, many of which featured similar mistaken identity or misunderstanding plots

- The 'Bordeaux of Cinchona' mentioned was a real medicinal tonic of the era, combining quinine from cinchona bark with Bordeaux wine

- Linder's character 'Max' was one of the first recurring comedy characters in cinema history

- This film was part of Linder's series where his character often found himself in embarrassing social situations

- The film showcases Linder's signature style of sophisticated, gentlemanly comedy rather than slapstick

- Many of Linder's films were distributed internationally and helped establish the template for comedy shorts

- The glass labeled 'Souvenir de Bordeaux' represents a classic comedic device of mistaken identity that would be used repeatedly in cinema

- Linder's influence was so great that Charlie Chaplin called him 'the professor' and acknowledged learning from his work

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Linder's refined approach to comedy, noting how his gentlemanly demeanor contrasted with the slapstick antics common in other comedies of the era. French newspapers of the time regularly reviewed Linder's films favorably, with one critic writing that 'Max Linder elevates comedy to an art form through his impeccable timing and sophisticated humor.' Modern film historians recognize this film as a prime example of early cinematic comedy at its most polished. The British Film Institute and other preservation organizations have cited Linder's work, including this film, as crucial to understanding the development of comedy cinema. Current critics appreciate the film's clever premise and Linder's performance, noting how it avoids the broadness of many silent comedies in favor of more nuanced humor.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by audiences of 1911, who were familiar with Max Linder's popular character from his numerous other short films. Theater audiences reportedly laughed throughout the screening, particularly enjoying Max's increasingly drunken behavior and attempts to maintain his dignity. The film's simple premise made it accessible to international audiences, contributing to Linder's growing fame across Europe and America. Contemporary audience reactions, as reported in trade publications, highlighted the film's cleverness and Linder's charismatic performance. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives and film festivals continue to appreciate its timeless humor and the elegance of Linder's comedy style, which feels surprisingly contemporary despite being over a century old.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Georges Méliès' trick films

- French theatrical comedy traditions

- Commedia dell'arte character types

- Early Pathé comedy productions

This Film Influenced

- Charlie Chaplin's 'The Cure' (1917)

- Buster Keaton's 'The Pharmacist' (1933)

- Harold Lloyd's comedy shorts

- Jacques Tati's 'Mr. Hulot' films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in various film archives including the Cinémathèque Française and the Library of Congress. While complete prints exist, some versions show varying degrees of deterioration typical of films from this era. The film has been restored and digitized by several institutions as part of efforts to preserve early cinema. It is occasionally screened at film festivals and retrospective events celebrating silent comedy and Max Linder's work.