Musical Story

Plot

Musical Story follows Petya, a talented taxi driver in Leningrad with a remarkable singing voice who dreams of becoming an opera star. He spends his evenings rehearsing with an amateur opera company, completely absorbed in his musical ambitions while neglecting his devoted girlfriend Tonya, who works as a taxi dispatcher at the same company. When Petya gets an unexpected opportunity to audition for the prestigious Leningrad Opera Theatre, he must confront the conflict between his artistic aspirations and his personal relationships. The film explores his journey as he navigates the challenges of pursuing professional opera while trying to maintain his connection with Tonya and his working-class roots. Through a series of musical performances and dramatic encounters, Petya ultimately learns to balance his dreams with the reality of love and responsibility.

About the Production

The film was a collaboration between directors Herbert Rappaport and Aleksandr Ivanovsky, with Rappaport handling the musical sequences. The production took advantage of Leningrad's authentic urban settings and the city's rich musical culture. The film featured real opera singers alongside actors, blurring the line between performance and reality. The musical numbers were recorded live on set rather than dubbed, which was unusual for the time and required extensive rehearsal.

Historical Background

Musical Story was produced during a significant period in Soviet cultural history, just before the outbreak of World War II. The late 1930s saw the Soviet Union under Stalin's rule promoting socialist realism in the arts, which demanded that cultural works be accessible to the masses while advancing communist ideals. This film emerged during a brief relaxation of cultural restrictions when musical comedies and lighter entertainment were temporarily encouraged to boost public morale. The film's emphasis on a working-class hero achieving artistic success through talent and dedication reflected Soviet ideals of social mobility and cultural democratization. The setting in Leningrad was particularly significant, as the city was considered the cultural capital of the Soviet Union. The film's release in April 1940 came at a tense time in European history, with the Soviet Union having recently signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany. Little did the filmmakers and audiences know that within a year, Leningrad would be under siege during one of the most brutal battles of World War II.

Why This Film Matters

Musical Story holds an important place in Soviet cinema history as one of the pioneering musical comedies that successfully blended popular entertainment with socialist values. The film helped establish the template for the Soviet musical genre, balancing accessible entertainment with ideological messaging. Its portrayal of a working-class character achieving success in the high art of opera represented the Soviet ideal of cultural democratization - the belief that great art should be accessible to and created by all social classes. The film's success demonstrated that Soviet audiences had an appetite for lighter entertainment alongside more serious ideological films. Sergey Lemeshev's performance helped bridge the gap between popular cinema and high culture, exposing millions of Soviet citizens to opera in an accessible format. The film also contributed to the development of the 'Soviet happy ending' formula that would dominate cinema for decades. Its temporary banning during the Zhdanovshchina period of the late 1940s ironically cemented its cultural significance, as it became associated with artistic freedom and resistance to ideological restrictions.

Making Of

The production of Musical Story faced several unique challenges during its filming in 1939-1940. The collaboration between directors Herbert Rappaport and Aleksandr Ivanovsky represented the meeting of Soviet and European cinematic traditions. Rappaport, an Austrian emigré, brought sophisticated musical staging techniques, while Ivanovsky contributed his deep understanding of Soviet audiences and cultural policies. The casting of real opera star Sergey Lemeshev in the lead role created both opportunities and challenges - while his singing was undeniably authentic, his acting required extensive coaching. The musical sequences were particularly complex to film, as the Soviet film industry at the time had limited experience with large-scale musical productions. The production team had to innovate with microphone placement and camera movement to capture both the musical performances and the dramatic action effectively. The film was completed just months before the outbreak of WWII, and its optimistic tone and celebration of Soviet cultural life took on new significance during the difficult war years that followed.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Musical Story was handled by Vladimir Rapoport, who employed innovative techniques for the musical sequences that were advanced for Soviet cinema of the era. The film utilized mobile camera movements during the musical numbers, creating a sense of dynamism that contrasted with the more static shots typical of Soviet films of the period. The urban scenes of Leningrad were filmed on location, providing authentic views of the city's architecture and street life in the late 1930s. The lighting design was particularly sophisticated for the opera house sequences, creating dramatic contrasts between the spotlighted performers and the darkened audience. The film made effective use of deep focus photography, especially in scenes showing both the performers and their reactions. The taxi depot sequences used natural lighting and documentary-style framing to emphasize the working-class setting. The cinematography successfully balanced the glamorous world of opera with the gritty reality of working-class Leningrad, creating a visual narrative that supported the film's themes of social mobility and cultural democratization.

Innovations

Musical Story introduced several technical innovations to Soviet cinema, particularly in the realm of sound recording and musical synchronization. The film was one of the first Soviet productions to use multiple microphone techniques for recording musical performances, allowing for more natural sound capture during the opera sequences. The production team developed new methods for synchronizing lip movements with pre-recorded music, a technique that would become standard in later Soviet musical films. The film also experimented with early forms of stereo sound during the opera house scenes, creating a more immersive audio experience for theater audiences. The camera movement during musical numbers was technically advanced for the time, using newly developed dollies and crane equipment that allowed for fluid tracking shots. The film's editing techniques, particularly in the musical montages, influenced later Soviet musical productions. The production also pioneered new approaches to recording dialogue in scenes with background music, improving the clarity and naturalness of the sound mix. These technical achievements helped establish new standards for musical filmmaking in the Soviet Union.

Music

The soundtrack of Musical Story was one of its most distinctive features, combining classical opera pieces with popular Soviet songs of the era. The musical supervision was handled by Vsevolod Zaderatsky, who carefully selected pieces that would be both artistically impressive and accessible to mass audiences. Sergey Lemeshev performed several famous opera arias, including pieces from Tchaikovsky's 'Eugene Onegin' and Rimsky-Korsakov's 'The Tsar's Bride,' demonstrating his extraordinary vocal range. The film also featured original songs composed specifically for the production, including 'The Taxi Driver's Song' which became a popular hit. The musical arrangements blended classical and popular styles, reflecting the Soviet ideal of creating a new people's art form. The sound recording was particularly challenging for the period, as the filmmakers attempted to capture both the power of operatic singing and the intimacy of dramatic dialogue. The film's soundtrack was released on gramophone records and became one of the best-selling musical recordings in the Soviet Union in 1940. The success of the film's music led to increased production of musical films in the Soviet Union during the early 1940s.

Famous Quotes

Even a taxi driver can reach the stars if he has the voice of an angel and the heart of a lion.

Love is like music - it needs practice, patience, and passion to become perfect.

The streets of Leningrad may be my workplace, but the opera stage is my destiny.

Every great artist was once an amateur who never gave up.

In Soviet Russia, art doesn't just belong to the palaces - it belongs to the people.

Memorable Scenes

- Petya's impromptu performance of 'Eugene Onegin' in the taxi depot, where his colleagues discover his extraordinary talent for the first time

- The emotional confrontation scene between Petya and Tonya in the rain, where she expresses her hurt over his neglect

- The grand opera audition sequence where Petya must prove himself to skeptical theater directors

- The final reconciliation scene where Petya performs a special song dedicated to Tonya, combining his artistic success with his love for her

- The opening montage showing Leningrad's streets and taxi drivers at work, establishing the film's urban working-class setting

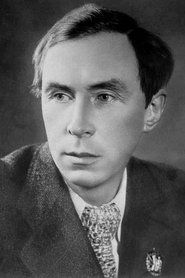

Did You Know?

- Sergey Lemeshev, who played the lead role of Petya, was actually one of the most famous tenors of the Bolshoi Theatre in real life, making his casting particularly authentic

- The film was temporarily withdrawn from circulation after WWII due to ideological concerns about its 'light entertainment' value during the Zhdanov Doctrine era

- Director Herbert Rappaport was originally from Austria and had emigrated to the Soviet Union, bringing European cinematic techniques to Soviet filmmaking

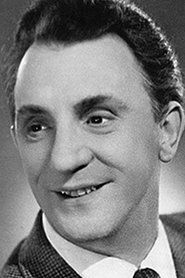

- Zoya Fyodorova, who played Tonya, was later arrested in 1946 during Stalin's purges and spent 10 years in labor camps before being rehabilitated

- The film's musical numbers included adaptations of popular Soviet songs and classical opera pieces that were carefully selected to appeal to both working-class and educated audiences

- The taxi company setting was based on real Leningrad taxi services of the 1930s, with authentic uniforms and vehicles used in the production

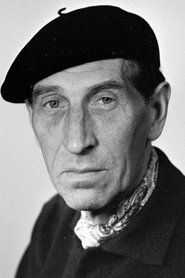

- Erast Garin, who played the comic relief character, was one of Soviet cinema's most beloved character actors known for his distinctive physical comedy style

- The film's success led to a stage musical adaptation that toured Soviet cities in the early 1940s

- The amateur opera company scenes were filmed with actual members of Leningrad workers' cultural clubs

- The film was one of the first Soviet musical comedies to feature a working-class protagonist as an opera singer, breaking from traditional class-based casting

What Critics Said

Upon its release in 1940, Musical Story received generally positive reviews from Soviet critics who praised its successful blend of entertainment and educational value. Critics particularly commended Sergey Lemeshev's performance, noting how effectively the renowned opera singer adapted to film acting. The film's musical sequences were highlighted as technically innovative for Soviet cinema of the period. However, some critics expressed concern that the film was too 'light' and didn't sufficiently emphasize socialist themes. After WWII, during the Zhdanov Doctrine era, the film was criticized for its 'formalism' and 'cosmopolitan' influences, leading to its temporary withdrawal from distribution. In later decades, particularly after the Khrushchev Thaw, the film was reevaluated and recognized as an important example of pre-war Soviet cinema. Modern film historians view Musical Story as a significant cultural artifact that reflects the complex relationship between art and politics in the Soviet Union.

What Audiences Thought

Musical Story was extremely popular with Soviet audiences upon its release in 1940, becoming one of the box office successes of that year. The film's combination of romance, comedy, and music appealed to a broad spectrum of viewers across the Soviet Union. Sergey Lemeshev's star power as a real opera singer drew audiences who were eager to see him in a film role. The relatable story of a working-class character pursuing artistic dreams resonated particularly strongly with urban audiences. During the Siege of Leningrad, the film gained additional emotional significance as a reminder of the city's vibrant cultural life before the war. After the war, despite its temporary official disfavor, the film remained popular through underground screenings and was eagerly awaited when it returned to official distribution in the 1950s. The film's songs became popular hits that were sung by ordinary people long after the film's theatrical run ended. Even today, among older generations in Russia and former Soviet republics, the film is remembered with nostalgia as representing a more optimistic era in Soviet cultural life.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- American musical comedies of the 1930s

- European operetta traditions

- Soviet socialist realist literature

- Italian neorealist cinema techniques

- German expressionist cinematography

This Film Influenced

- Kuban Cossacks (1949)

- The Composer Glinka (1952)

- The Nightingale (1979)

- Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears (1980)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Musical Story has been preserved in the Gosfilmofond of Russia, the state film archive. The original nitrate negatives survived World War II despite the Siege of Leningrad, though some damage occurred during storage. The film underwent digital restoration in the 2000s as part of a broader effort to preserve classic Soviet cinema. The restored version was screened at several international film festivals and released on DVD. Some scenes from the original release are believed to be lost, particularly musical numbers that were cut during the film's temporary banning in the late 1940s. The soundtrack has been particularly well-preserved, with high-quality audio recordings of the musical numbers surviving in the state sound archives. The film is considered to be in good preservation condition compared to other Soviet films of the same era.