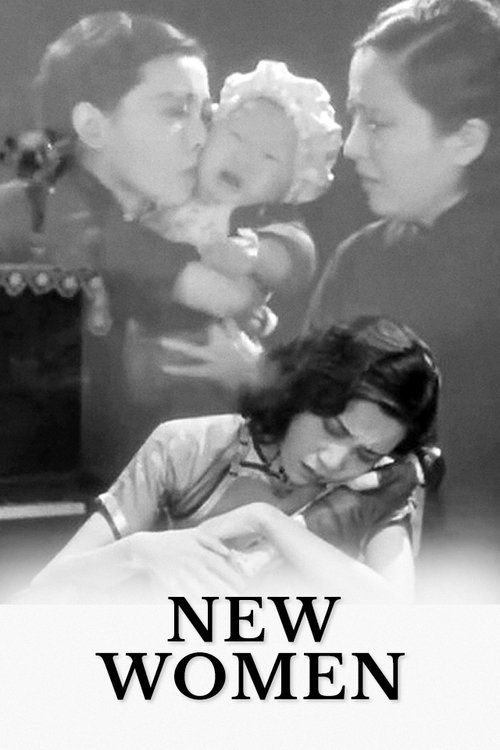

New Women

"A woman's struggle for independence in a man's world"

Plot

The film follows Wei Ming, a successful novelist and single mother struggling to support her young daughter who suffers from tuberculosis. Facing mounting medical bills and constant harassment from wealthy, predatory men, Wei Ming finds herself trapped between her moral values and desperate need for money. Despite her literary success and independence, she ultimately succumbs to becoming a high-class prostitute to fund her daughter's treatment. The film powerfully critiques the hypocrisy of 1930s Chinese society, where educated women like Wei Ming are denied genuine opportunities for self-sufficiency and are instead exploited by the patriarchal system. Her tragic journey from intellectual achievement to moral compromise serves as a devastating commentary on the limited choices available to women seeking autonomy in a conservative society.

About the Production

The film was shot at Lianhua's studios in Shanghai during a period of intense social and political upheaval in China. Director Cai Chusheng faced significant censorship challenges from both Nationalist government authorities and conservative social elements who found the film's critique of social hypocrisy too radical. The production was particularly notable for its realistic portrayal of urban life in 1930s Shanghai and its unflinching examination of prostitution and women's exploitation.

Historical Background

'New Women' was produced during a tumultuous period in Chinese history, as the country faced internal political divisions, Japanese invasion, and rapid social transformation. The 1930s saw the rise of the New Culture Movement, which advocated for modernization, women's rights, and social reform. Shanghai, where the film was made, was a cosmopolitan hub experiencing rapid industrialization and Westernization, creating tensions between traditional values and modern aspirations. The film emerged during the peak of leftist cultural activity in Shanghai, with many artists and intellectuals using their work to critique social injustice and advocate for change. The Nationalist government's increasing censorship and political repression created a dangerous environment for filmmakers addressing controversial topics. The film's release coincided with growing anti-Japanese sentiment and calls for national unity, adding layers of political significance to its social critique.

Why This Film Matters

'New Women' stands as a landmark achievement in Chinese cinema history, representing both artistic excellence and social courage. The film's unflinching examination of women's oppression and social hypocrisy was groundbreaking for its time, establishing a template for socially conscious cinema in China. Ruan Lingyu's performance became legendary, influencing generations of Chinese actresses and establishing her as an enduring symbol of artistic integrity and tragic sacrifice. The film's impact extended beyond cinema, contributing to broader discussions about women's rights and social reform in 1930s China. Its tragic connection to Lingyu's real-life suicide elevated the film to mythic status, making it a powerful cautionary tale about the destructive power of media sensationalism and social judgment. The film has been extensively studied by film scholars and feminists as a seminal work of early feminist cinema, and its themes continue to resonate with contemporary audiences. Its rediscovery and restoration in the 1980s sparked renewed interest in China's cinematic heritage and influenced a new generation of Chinese filmmakers.

Making Of

The making of 'New Women' was marked by intense controversy and tragedy. Director Cai Chusheng, known for his social realist approach, worked closely with Ruan Lingyu to create a deeply authentic portrayal of a modern woman's struggles. The filming process was emotionally taxing for Lingyu, who reportedly identified strongly with her character's plight. The production faced constant pressure from censors who objected to the film's critical view of Chinese society and its sympathetic portrayal of a prostitute. After the film's release, Lingyu was subjected to vicious media attacks and gossip columns that sensationalized her personal life, paralleling the film's themes of social hypocrisy. The intense public scrutiny and personal attacks contributed significantly to her decision to take her own life, making the film tragically prophetic. Cai Chusheng was devastated by Lingyu's death and the controversy surrounding the film, which temporarily damaged his career but ultimately cemented his reputation as a courageous filmmaker willing to tackle difficult social issues.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'New Women' was groundbreaking for its time, employing sophisticated techniques that were innovative in 1930s Chinese cinema. Cinematographer Wong Chung-yiu used dramatic lighting and camera angles to emphasize the emotional states of the characters, particularly Wei Ming's psychological deterioration. The film's urban sequences captured the modernity and chaos of 1930s Shanghai with remarkable visual poetry, contrasting the glamour of the city with the desperation of its inhabitants. The use of close-ups was particularly effective in conveying the characters' inner turmoil, while the composition of shots often created visual metaphors for the social constraints faced by women. The film's visual style combined European cinematic influences with distinctly Chinese aesthetic sensibilities, creating a unique visual language that enhanced its narrative power.

Innovations

'New Women' showcased several technical innovations that were advanced for Chinese cinema in 1935. The film employed sophisticated editing techniques, including cross-cutting and montage sequences that effectively conveyed the passage of time and the psychological states of characters. The sound recording quality was notably superior to many contemporary Chinese films, allowing for more nuanced performances and dialogue delivery. The production design was meticulous in its recreation of 1930s Shanghai, providing an authentic backdrop that enhanced the film's realism. The film's makeup and costume design were particularly noteworthy, effectively showing the transformation of Wei Ming from an intellectual to a woman forced into prostitution. The film also demonstrated advanced understanding of pacing and narrative structure, maintaining dramatic tension throughout its relatively lengthy runtime.

Music

The film's soundtrack was composed by prominent Chinese composer He Luting, who created a score that blended traditional Chinese musical elements with Western orchestral techniques. The music played a crucial role in establishing the film's emotional atmosphere, particularly in scenes depicting Wei Ming's psychological distress and moral conflict. The film featured several popular songs of the era, including the theme song 'New Women' which became widely known and contributed to the film's cultural impact. The sound design was innovative for its time, using diegetic and non-diegetic sound to create a rich auditory environment that enhanced the film's realism and emotional depth. The soundtrack's integration with the visual narrative demonstrated the sophisticated understanding of cinematic language that characterized the best films of this period.

Famous Quotes

I'd rather die than be a plaything for men - Wei Ming

A woman's independence is just an illusion in this society - Wei Ming

The world calls me a new woman, but I'm still trapped in the old cage - Wei Ming

My pen can't feed my child, but my body can - Wei Ming

They praise my mind but want my body - Wei Ming

In this world, a woman's virtue is measured by her suffering - Wei Ming

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene showing Wei Ming typing her novel while caring for her sick daughter, establishing the central conflict between her intellectual life and maternal responsibilities

- The confrontation scene where Wei Ming faces the wealthy patron who offers her money in exchange for sexual favors, highlighting the power dynamics and economic desperation

- The sequence showing Wei Ming's transformation from intellectual to prostitute, using subtle changes in costume and makeup to mark her moral compromise

- The final scene where Wei Ming, broken and defeated, walks through the streets of Shanghai, symbolizing her complete loss of self and agency

- The scene where Wei Ming reads her own published novel, the irony of her literary success contrasting with her personal tragedy

Did You Know?

- Ruan Lingyu committed suicide on March 8, 1935, just weeks after the film's release, allegedly due to the intense media scrutiny and scandal surrounding her personal life and the film's controversial themes

- The film was based on the real-life story of actress Ai Xia, who also committed suicide in 1934 under similar circumstances

- The original script was heavily censored by the Nationalist government, forcing director Cai Chusheng to make multiple revisions before approval

- The film's depiction of prostitution was so controversial that it was temporarily banned in several Chinese cities

- Ruan Lingyu's final film - her suicide note famously read 'Gossip is a fearful thing'

- The film was considered lost for decades before being rediscovered and restored in the 1980s

- Director Cai Chusheng was forced to write a self-criticism after the film's release due to its perceived negative portrayal of Chinese society

- The film's title 'New Women' was ironic, as it showed how modern, educated women still faced the same oppression as traditional women

- The character of Wei Ming was partially inspired by real-life women writers struggling in 1930s Shanghai

- The film's release coincided with the height of the New Culture Movement in China, which advocated for women's rights and modernization

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to 'New Women' was deeply divided and intensely passionate. Progressive intellectuals and leftist critics praised the film for its courageous social commentary and artistic excellence, hailing it as a masterpiece of Chinese cinema. However, conservative critics and government officials condemned the film as morally corrupting and unpatriotic, arguing that it presented a negative image of Chinese society to foreign audiences. The film's realistic depiction of prostitution and social injustice was particularly controversial, with many calling for its ban. In the decades following its release, 'New Women' has been reevaluated by film scholars and critics who now recognize it as one of the most important and influential works in Chinese cinema history. Modern critics praise the film's sophisticated narrative structure, powerful performances, and bold social critique, considering it far ahead of its time in both artistic technique and social consciousness.

What Audiences Thought

The film's reception among audiences in 1935 was intense and polarized. Urban audiences, particularly educated women and young intellectuals, responded strongly to the film's honest portrayal of modern women's struggles, finding validation in its depiction of their own experiences. The film generated enormous public discussion and debate, becoming a cultural phenomenon that extended beyond cinema into broader social conversations about women's roles and social reform. However, conservative elements of society were outraged by the film's sympathetic portrayal of a prostitute and its critique of traditional values. The tragic suicide of Ruan Lingyu shortly after the film's release intensified public reaction, turning the film into a symbol of the destructive power of social hypocrisy and media sensationalism. In subsequent decades, as the film was rediscovered and restored, it has developed a cult following among film enthusiasts and scholars who appreciate its artistic merit and historical significance.

Awards & Recognition

- Named one of the 100 greatest Chinese films of the 20th century by Hong Kong Film Awards in 2005

- Recognized as a masterpiece of Chinese cinema at various international retrospectives

Film Connections

Influenced By

- European realist cinema of the 1930s

- Soviet social realist films

- German expressionist cinema

- The New Culture Movement's literary works

- Realist novels by Lu Xun and other May Fourth writers

This Film Influenced

- Spring in a Small Town (1948)

- The Spring River Flows East (1947)

- The Red Detachment of Women (1961)

- Farewell My Concubine (1993)

- In the Mood for Love (2000)

- The Story of Qiu Ju (1992)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for several decades before being rediscovered and restored in the 1980s by the China Film Archive. The restoration process involved piecing together multiple incomplete prints and reconstructing damaged sections. The restored version has been preserved in digital format and is periodically screened at international film festivals and retrospectives. While some scenes remain incomplete or damaged, the majority of the film has been successfully preserved and is considered one of the most important surviving works of 1930s Chinese cinema.