Peat-Bog Soldiers

"Where the spirit of freedom cannot be broken, even in the darkest camps of tyranny"

Plot

Set in the brutal environment of Nazi concentration camps during the 1930s, the film follows a group of Communist political prisoners who are subjected to systematic psychological and physical torture by their Nazi captors. The guards employ various methods to break the prisoners' revolutionary spirit, including forced labor in the peat bogs, starvation, and psychological manipulation. Despite these harsh conditions, the prisoners maintain their solidarity and ideological commitment, organizing resistance within the camp and preserving their humanity through mutual support. The narrative culminates in a powerful demonstration of human resilience as the prisoners unite in song, specifically 'The Peat Bog Soldiers' anthem, transforming their suffering into an act of defiance. The film explores themes of political conviction, friendship, and the indomitable human spirit in the face of fascist oppression.

About the Production

The film was one of the earliest cinematic depictions of Nazi concentration camps, created before the full extent of the Holocaust was known to the world. Production took place during Stalin's Great Purge, making it a politically sensitive project that had to balance anti-fascist messaging with Soviet ideological requirements. The filmmakers faced challenges in realistically depicting camp conditions while adhering to Soviet censorship standards. The peat bog scenes were particularly difficult to film, requiring extensive set construction to replicate the harsh environment of actual Nazi camps.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a critical period in European history when Nazi Germany was rapidly expanding its power and influence. In 1938, the Anschluss with Austria had just occurred, and the Munich Agreement was being negotiated, effectively ceding Czechoslovakia to Germany. The Soviet Union under Stalin was promoting an anti-fascist Popular Front policy, encouraging cultural works that exposed the dangers of Nazism. However, this was also the height of Stalin's Great Purge (1936-1938), during which millions were arrested and executed. This paradoxical situation created a complex environment for filmmakers who had to condemn Nazi brutality while ignoring Soviet repression. The film's release came just before the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, which temporarily aligned the Soviet Union with Nazi Germany and led to the withdrawal of such anti-fascist films from circulation.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the earliest cinematic exposures of Nazi concentration camps, the film played a crucial role in international awareness of Nazi atrocities. It became a powerful propaganda tool for anti-fascist movements worldwide and was screened at workers' meetings, Communist party gatherings, and anti-fascist rallies across Europe and America. The film helped popularize 'The Peat Bog Soldiers' song as an anthem of resistance against fascism. Its influence extended beyond cinema, inspiring theatrical productions, literature, and political art. The film established a template for subsequent concentration camp narratives and demonstrated cinema's potential as a weapon against totalitarianism. Despite its Soviet origins, it transcended ideological boundaries to become a universal statement about human dignity and resistance.

Making Of

The production faced numerous challenges due to its sensitive subject matter. Filming took place under intense scrutiny from Soviet authorities who were simultaneously conducting their own purges. The cast and crew had to carefully navigate the fine line between exposing Nazi atrocities and avoiding any criticism of Soviet prison systems. Many of the actors studied accounts of German political prisoners to prepare for their roles, and some consulted with German Communist exiles who had fled to the Soviet Union. The peat bog sets were constructed on the outskirts of Moscow using tons of imported peat and water to create authentic swamp conditions. The film's production coincided with the Munich Agreement and the escalating tensions in Europe, adding urgency to its anti-fascist message. Despite the political pressures, Macheret insisted on maintaining the artistic integrity of the story, refusing to compromise on the realistic depiction of camp conditions.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Boris Volchek employed stark, high-contrast lighting to emphasize the brutal conditions of the camps. The peat bog sequences were shot with wide angles to convey the vast, oppressive landscape, while close-ups were used to capture the prisoners' expressions of defiance and suffering. Volchek utilized deep focus techniques to maintain both foreground and background clarity, creating a documentary-like authenticity. The camera work often remained static during torture scenes, forcing viewers to witness the brutality without escape. The visual style incorporated elements of German Expressionism, particularly in the portrayal of the Nazi guards, whose shadows loomed large across the camp grounds. The contrast between the dark, muddy camp interiors and the occasional bright exterior shots symbolized hope and the possibility of resistance.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations for Soviet cinema of the 1930s. The production team developed new techniques for creating realistic mud and water effects on set, using a combination of peat moss, cellulose, and controlled water systems. The sound recording equipment was modified to capture dialogue clearly in the challenging acoustic environment of the constructed swamp sets. The film also experimented with early forms of handheld camera work during the resistance sequences to create a sense of immediacy and authenticity. The makeup department developed new prosthetic techniques to realistically portray the physical deterioration of prisoners over time. The film's editing style, particularly in the montage sequences showing the passage of time in the camps, influenced subsequent Soviet war films.

Music

The musical score was composed by Lev Shvarts, who incorporated the actual 'Peat Bog Soldiers' melody as a recurring theme throughout the film. The soundtrack blended traditional Russian folk elements with modernist dissonance to reflect the prisoners' suffering and resilience. Choral arrangements of the resistance songs were performed by the Moscow State Academic Chorus, adding authenticity to the musical sequences. The sound design emphasized the oppressive atmosphere of the camps, with amplified sounds of marching boots, guard dogs, and the constant dripping of water in the peat bogs. The musical moments of collective singing were carefully orchestrated to represent the prisoners' unity and defiance. The score received particular praise for its ability to convey emotional depth without resorting to melodramatic clichés.

Famous Quotes

They can break our bodies, but they cannot break our spirit. In the mud of this peat bog, we plant the seeds of freedom.

Every shovelful of peat we dig is a shovelful of our own grave, but also a brick for the foundation of a new world.

When they take away our bread, we sing. When they take away our names, we remember. When they take away our lives, we become immortal.

The guards think they own this camp, but we own the songs in our hearts and the ideas in our minds.

In this hell on earth, we have discovered that the only thing more powerful than their guns is our unity.

Tomorrow belongs to those who endure today.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the arrival of prisoners at the camp, shot with stark, documentary-like realism

- The collective singing of 'The Peat Bog Soldiers' anthem during a forced labor break, transforming the prisoners from victims to resisters

- The secret nighttime meeting where prisoners organize resistance, illuminated only by moonlight through the barbed wire

- The confrontation scene where the lead prisoner refuses to betray his comrades despite extreme torture

- The final sequence showing the prisoners marching together, their faces showing both suffering and unbroken determination

- The moment when a guard hesitates after hearing the prisoners sing, revealing a crack in the fascist facade

Did You Know?

- The film is based on the famous anti-fascist song 'Die Moorsoldaten' (The Peat Bog Soldiers), written by political prisoners in the Börgermoor concentration camp in 1933

- It was one of the first films internationally to expose the existence and conditions of Nazi concentration camps

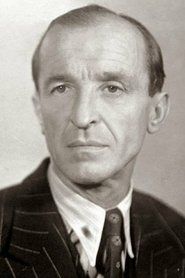

- Director Aleksandr Macheret was later arrested during Stalin's purges in 1939, shortly after completing this film

- The film was banned in Nazi Germany and all occupied territories during World War II

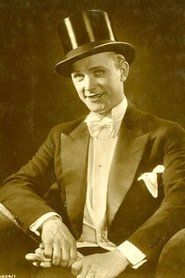

- Oleg Zhakov, who played one of the lead roles, would later become one of the Soviet Union's most respected dramatic actors

- The peat bog sequences required actors to work in actual mud and water conditions for extended periods

- The film's title in Russian is 'Torfyanye soldaty' (Торфяные солдаты)

- It was screened internationally at anti-fascist rallies and congresses before WWII

- The musical score incorporates variations of the actual 'Peat Bog Soldiers' song

- The film was considered lost for decades before being rediscovered in Soviet archives in the 1970s

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its powerful anti-fascist message and artistic merit, with Pravda calling it 'a brilliant indictment of Nazi barbarism and a testament to the unbreakable spirit of the working class.' International critics, particularly in leftist publications, hailed it as a courageous expose of Nazi crimes. Western mainstream press gave it more mixed reviews, with some questioning its propaganda elements while acknowledging its historical importance. Modern critics and film historians recognize it as a historically significant work that, despite some ideological limitations, effectively documented the early nature of Nazi concentration camps. The film is now studied as an important example of anti-fascist cinema and as a historical document of pre-WWII awareness of Nazi atrocities.

What Audiences Thought

The film was received enthusiastically by Soviet audiences, particularly workers and intellectuals who understood its political significance. It became especially popular among Communist Party members and was frequently shown at party meetings and educational institutions. International audiences at anti-fascist gatherings responded emotionally to its depiction of resistance. However, after the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in 1939, the film was withdrawn from Soviet circulation and became difficult to see for nearly two decades. Post-war audiences rediscovered it as an important historical document. Modern audiences viewing the film in retrospectives and film festivals often comment on its prescience and emotional power, while noting its period-specific stylistic elements.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize (Second Degree) for 1938

- Honorable Mention at the Venice Film Festival, 1938

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema of the 1920s

- Soviet socialist realist film tradition

- Documentary footage of early Nazi camps

- John Steinbeck's 'The Grapes of Wrath' (thematically)

- Bertolt Brecht's epic theater techniques

- The actual 'Peat Bog Soldiers' song and its history

- Leni Riefenstahl's propaganda films (as counter-influence)

This Film Influenced

- The Great Dictator (1940)

- Mister Johnson (1939)

- The Long Walk (1940)

- The North Star (1943)

- None Shall Escape (1944)

- The Seventh Cross (1944)

- Kapo (1960)

- The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)

- The Prisoner (1963 TV series)

- Schindler's List (1993)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered partially lost for many years after being withdrawn from circulation following the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. It was rediscovered in the Gosfilmofond archive in the 1970s in relatively complete condition. A restoration project was undertaken in the 1990s by the Russian State Archive of Film and Photo Documents, which preserved the original nitrate elements and created new safety prints. The restored version has been screened at various international film festivals and is now considered well-preserved. Digital restoration was completed in 2015, ensuring the film's long-term survival. The original Russian version is intact, though some international versions with different edits may have been lost.