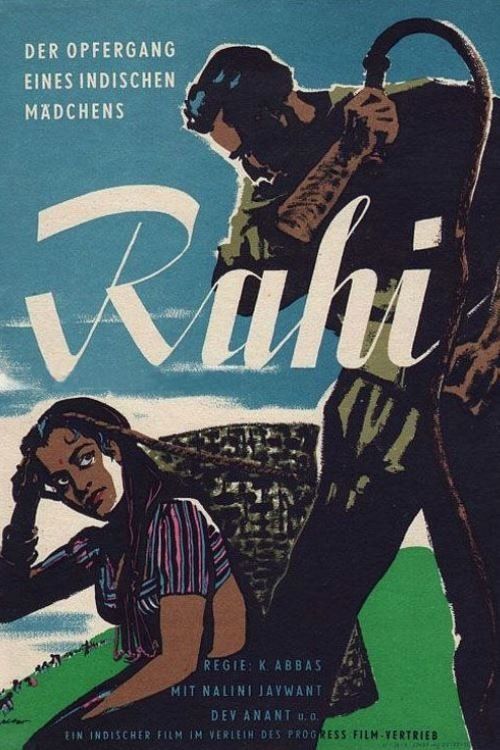

Rahi

Plot

Ramesh, a young Indian man who served in the British Army during World War II, returns to India and takes a job as a supervisor at a British-owned tea plantation in Assam. Initially, he follows his employer's orders to harass and exploit the local Indian workers, seeing it as his duty to maintain the plantation's productivity. However, as he witnesses the brutal treatment of his countrymen and develops feelings for a local village girl named Kamla, his conscience begins to awaken. The transformation culminates in Ramesh joining the workers' struggle against their colonial oppressors, leading a revolt that challenges both the British authority and his own conflicted identity. The film explores themes of colonialism, nationalism, and personal redemption against the backdrop of India's independence movement.

About the Production

The film was shot on location in actual tea plantations in Assam to capture the authentic atmosphere and working conditions. Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, known for his socially conscious cinema, faced challenges from British authorities during filming due to the film's anti-colonial themes. The production employed many local Assamese people as extras to maintain authenticity in depicting the plantation workers' lives.

Historical Background

Rahi was produced in 1953, just six years after India's independence from British rule, during a period when the nation was grappling with the legacy of colonialism and the challenges of building a new society. The film reflected the growing trend in Indian cinema towards addressing social and political issues, moving away from pure entertainment. The early 1950s saw the emergence of parallel cinema in India, with filmmakers like Abbas, Satyajit Ray, and Bimal Roy creating works that examined the realities of Indian society. The tea plantations of Assam, where the film is set, had been sites of significant exploitation during British rule, with workers often living in conditions akin to indentured servitude. This historical context gave Rahi particular relevance as it examined not just the political independence of India but the economic and social liberation of its people.

Why This Film Matters

Rahi holds an important place in Indian cinema history as one of the early examples of socially relevant filmmaking that combined entertainment with political consciousness. The film contributed to the development of what would later be known as 'parallel cinema' or 'art house cinema' in India. It was among the first mainstream Indian films to directly critique colonial economic structures and their continuing impact on independent India. The film's portrayal of the tea plantation workers' struggle helped raise national awareness about labor issues in remote regions of India. Rahi also demonstrated that commercial actors like Dev Anand could successfully transition to more serious, socially conscious roles, paving the way for other mainstream stars to take on similar projects. The film's success proved that audiences were ready for cinema that addressed real social issues, influencing a generation of filmmakers to explore similar themes.

Making Of

Director Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, a committed socialist and progressive filmmaker, conceived Rahi as part of his trilogy of films addressing social issues in newly independent India. The production faced numerous challenges, including obtaining permission to film in the tea plantations and dealing with suspicious British plantation owners who were uncomfortable with the film's subject matter. Dev Anand, who was primarily known for his romantic roles at the time, was eager to take on this serious role to prove his versatility as an actor. The cast spent several weeks living in Assam before filming began to understand the local culture and working conditions. The film's realistic depiction of plantation life was achieved through extensive research and consultation with actual plantation workers, some of whom served as technical advisors during the production.

Visual Style

The cinematography by V.K. Murthy employed stark contrasts between the lush beauty of the Assam tea gardens and the harsh reality of the workers' lives. Murthy used deep focus techniques to capture both the expansive landscapes and intimate human moments within the same frame. The black and white photography emphasized the social divisions in the plantation, with the British supervisors often shot in bright light while Indian workers were frequently shown in shadows. The camera work during the revolt sequences used handheld techniques to create a sense of urgency and authenticity. Murthy's composition often placed characters against the vast tea gardens, emphasizing their smallness against the overwhelming economic and social structures they faced. The visual style combined documentary-like realism with carefully composed artistic shots, creating a distinctive aesthetic that influenced subsequent Indian social films.

Innovations

Rahi was technically innovative for its time in several aspects. The film pioneered the use of location shooting in remote areas of India, setting a precedent for realistic filmmaking. The sound recording techniques used during the plantation scenes were advanced for the period, capturing ambient sounds of the tea gardens to enhance authenticity. The film's editing style, particularly during the revolt sequences, employed rapid cuts that were unusual in Indian cinema of the era. The production design successfully recreated the colonial-era atmosphere using actual plantation buildings and minimal studio sets. The film also experimented with narrative structure, using flashbacks to reveal the protagonist's past in the British Army, a technique not commonly used in Indian films of the 1950s. These technical achievements contributed to the film's realistic feel and helped establish new standards for Indian cinema's technical capabilities.

Music

The music for Rahi was composed by the renowned duo Shankar-Jaikishan, with lyrics by Shailendra and Hasrat Jaipuri. The soundtrack featured a mix of classical Indian melodies and folk influences from Assam, reflecting the film's geographical setting. The songs were not mere entertainment but served to advance the narrative and express the characters' inner conflicts. Particularly notable was the use of Assamese folk instruments in the orchestration, which added authenticity to the film's setting. The soundtrack included both romantic numbers and protest songs, with the latter becoming particularly popular among progressive circles. The song 'Aaj Phir Jeene Ki Tamanna Hai' (though more famous from another film) had a similar spirit to some of Rahi's tracks expressing hope and resistance. The music received critical acclaim for its ability to blend commercial appeal with social consciousness, a hallmark of Shankar-Jaikishan's work.

Famous Quotes

When a man sees his own people suffering, he cannot remain a servant to their oppressors

This land may belong to the British on paper, but its soul belongs to those who work it

Love for one's country begins with love for one's people

Freedom is not just about removing foreign rulers, but about ending all forms of exploitation

In every worker's eyes, I saw the reflection of my own slavery

Memorable Scenes

- The powerful sequence where Ramesh witnesses the brutal punishment of a worker and his conscience awakens

- The romantic interlude between Ramesh and Kamla by the tea garden stream, contrasting natural beauty with human suffering

- The climactic revolt scene where workers unite against their British oppressors, set against the backdrop of the vast tea plantations

- Ramesh's internal conflict scene where he burns his British Army uniform, symbolizing his rejection of colonial identity

- The final confrontation between Ramesh and the British plantation owner, representing the larger conflict between India and British imperialism

Did You Know?

- Rahi was one of the first Indian films to directly address the exploitation of tea plantation workers in Assam

- The film was banned in several British territories due to its strong anti-colonial message

- Dev Anand took a significant pay cut to work on this socially relevant project

- Director Khwaja Ahmad Abbas wrote the screenplay based on his own experiences visiting Assam tea plantations

- The film's title 'Rahi' means 'traveler' or 'wayfarer' in Hindi, symbolizing the protagonist's journey of self-discovery

- Balraj Sahni, who played a supporting role, was a close associate of director Abbas and appeared in many of his socially conscious films

- The film was shot in black and white despite the availability of color technology to emphasize the stark reality of plantation life

- Nalini Jaywant's performance was particularly praised for bringing depth to the role of the village girl who becomes the catalyst for change

- The film's release coincided with India's early years of independence, making its themes particularly resonant

- Rahi was selected for screening at several international film festivals, bringing attention to Indian social cinema

What Critics Said

Upon its release, Rahi received widespread critical acclaim for its bold storytelling and social relevance. Critics praised Khwaja Ahmad Abbas's direction for balancing entertainment with social commentary without becoming preachy. The performances, particularly Dev Anand's departure from his usual romantic image, were noted for their authenticity and emotional depth. Filmfare magazine called it 'a landmark in Indian cinema that dares to speak truth to power.' International critics at film festivals where it was screened appreciated its universal themes of oppression and liberation. Modern film historians consider Rahi a precursor to the Indian New Wave cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. The film is often cited in academic studies of post-colonial Indian cinema as an example of how popular cinema engaged with the nation-building process in early independent India.

What Audiences Thought

Rahi resonated strongly with Indian audiences in the early 1950s, particularly among the educated middle class and urban workers who could relate to its themes of social justice. The film performed well in major cities like Bombay, Calcutta, and Delhi, though it had more limited commercial success in rural areas. Audiences appreciated Dev Anand's transformation from a romantic hero to a socially conscious character, which expanded his fan base. The film's depiction of the Assam tea plantations introduced many viewers to a part of India they knew little about, generating interest in the region's social issues. Despite its serious themes, the film's emotional core and romantic subplot helped it connect with general audiences. Over the years, Rahi has developed a cult following among cinema enthusiasts and is frequently screened at film festivals and retrospectives dedicated to classic Indian cinema.

Awards & Recognition

- Filmfare Award for Best Story - Khwaja Ahmad Abbas

- National Film Award - Certificate of Merit for Best Feature Film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Italian Neorealism

- Russian socialist cinema

- Indian independence movement literature

- Progressive Writers' Movement

- Bengali social cinema

This Film Influenced

- Maa Tujhe Salaam

- Ankur

- Nishant

- Manthan

- Aakrosh

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Rahi is partially preserved at the National Film Archive of India, though some prints have suffered from nitrate deterioration common in films of that era. The Film Heritage Foundation has undertaken restoration work on surviving elements. Several versions exist in different archives worldwide, with varying degrees of completeness. The film is occasionally screened at classic film festivals and retrospectives, but a fully restored digital version is not yet available to the general public.