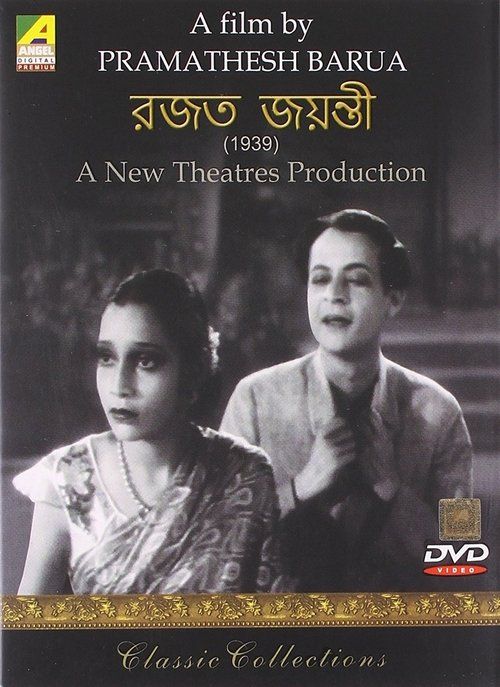

Rajat Jayanti

Plot

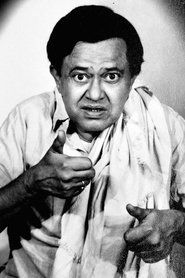

The film follows Rajat, a simple-minded young man played by P.C. Barua, who falls deeply in love with his neighbor Jayanti. His streetsmart cousin Bishwanath, portrayed by Pahadi Sanyal, along with Bishwanath's friend Samir (Bhanu Banerjee), attempts to guide Rajat in his romantic pursuits with often comical results. The plot thickens when Bishwanath and Samir try to secure money from Rajat's miserly guardian Bagalcharan, claiming they need funds to produce a 'European-style art film.' Their plans go awry when the guardian is admitted to Dr. Gajanan's clinic, where he falls victim to two professional crooks, Natoraj and Supta, who have their own sinister agenda involving Jayanti and attempt to kidnap her, leading to a dramatic confrontation.

About the Production

Rajat Jayanti was produced by New Theatres, one of the most prestigious film production companies in colonial India during its golden era. The film was made at the height of Bengali cinema's creative renaissance, when New Theatres was producing films that combined artistic merit with popular appeal. P.C. Barua, who both directed and starred in the film, was one of the pioneering figures of Indian cinema, known for his innovative techniques and ability to blend social themes with entertainment. The production faced the typical challenges of 1930s filmmaking, including limited technical equipment and the need to record sound live on set, but benefited from New Theatres' relatively advanced facilities and technical expertise.

Historical Background

Rajat Jayanti was produced in 1939, on the eve of World War II, during a period of significant political and social upheaval in India. The country was under British colonial rule, and the independence movement was gaining momentum with leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and Subhas Chandra Bose becoming increasingly prominent. Cinema during this period often served as both entertainment and a subtle medium for social commentary, with filmmakers navigating the constraints of colonial censorship while addressing contemporary issues. Bengali cinema, in particular, was experiencing a cultural renaissance, with filmmakers like P.C. Barua, Debaki Bose, and others creating films that combined artistic merit with social relevance. The film industry was also dealing with the challenges of technological transition, having fully embraced sound technology while still developing the grammar of cinematic storytelling. The year 1939 also saw the establishment of the Film Advisory Board in India, which was created to coordinate wartime film production, reflecting how global politics was beginning to influence Indian cinema.

Why This Film Matters

Rajat Jayanti represents an important phase in the development of Indian narrative cinema, particularly in the Bengali film industry. As a product of New Theatres, the studio that pioneered many technical and artistic innovations in Indian cinema, the film contributed to the establishment of cinematic conventions that would influence later generations of filmmakers. P.C. Barua's work, including this film, helped establish the prototype of the romantic hero in Indian cinema, blending vulnerability with determination. The film's exploration of themes like love, deception, and social hierarchy reflected the changing social dynamics of Bengal in the late colonial period. While not as well-remembered as some of Barua's other works like Devdas, Rajat Jayanti forms part of the foundation upon which the golden age of Indian cinema was built, showcasing the industry's ability to create sophisticated narratives that could entertain while also reflecting contemporary social realities. The film also represents the cosmopolitan nature of Bengali cinema in the 1930s, which was open to influences from both Indian traditional arts and European cinema.

Making Of

The making of Rajat Jayanti took place during a significant period in Indian cinema history when the industry was transitioning from silent films to talkies and establishing its own unique cinematic language. P.C. Barua, who had already established himself as a prominent filmmaker with earlier successes like Devdas (1935), brought his directorial expertise to this project while also taking on the challenging lead role. The film was shot at the New Theatres studio in Calcutta, which was equipped with state-of-the-art facilities for the time, including advanced sound recording equipment. The production team faced the typical challenges of filmmaking in the 1930s, including the need to record sound live on set due to the limitations of post-production technology. Barua's dual role as director and lead actor required careful coordination, and he often had to direct scenes while also performing in them, a practice that was more common in early cinema than it is today. The supporting cast, including Pahadi Sanyal and Bhanu Banerjee, were established actors in the Bengali film industry who brought their own expertise to the production.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Rajat Jayanti would have reflected the technical standards and artistic sensibilities of New Theatres in the late 1930s. While specific details about the cinematographer are not readily available, the studio was known for its high production values and technical excellence. The film would have been shot in black and white, using the lighting and camera techniques that were becoming standard in Indian cinema at the time. The visual style likely included carefully composed shots that balanced the need for clear storytelling with artistic composition. Indoor scenes would have been lit to create depth and mood, while outdoor sequences would have taken advantage of natural light where possible. The cinematography would have served the narrative needs of the film while also contributing to its overall aesthetic appeal. New Theatres was known for its relatively sophisticated approach to visual storytelling, and this would have been reflected in the cinematography of Rajat Jayanti.

Innovations

Rajat Jayanti was produced during a period of significant technical development in Indian cinema. As a New Theatres production, it would have benefited from the studio's commitment to technical excellence and innovation. The film would have used the sound recording technology available in 1939, which represented a significant improvement over early sound films. The studio was known for its relatively sophisticated lighting equipment and camera capabilities, allowing for more dynamic visual storytelling than was possible in earlier years. The editing techniques would have been evolving to better serve narrative needs, with more sophisticated use of cuts and transitions. While the film may not have introduced groundbreaking technical innovations, it would have represented the state-of-the-art in Indian film production of its time. New Theatres was one of the few studios in India that could match international technical standards, and this would have been reflected in the production quality of Rajat Jayanti.

Music

The soundtrack of Rajat Jayanti would have been typical of Bengali films of the late 1930s, featuring a mix of songs and background music that enhanced the narrative. While specific information about the music director or songs is not readily available, New Theatres productions were known for their quality music, often featuring compositions that blended traditional Bengali musical elements with contemporary influences. The songs would have been an integral part of the film's appeal, as music was a crucial component of Indian cinema even in these early years of sound films. The background score would have helped establish mood and enhance emotional moments in the narrative. The sound recording technology of the period would have presented challenges, but New Theatres was equipped with relatively advanced facilities for the time. The music would have been recorded live during filming, as was the practice in Indian cinema during this period.

Memorable Scenes

- The scenes where Rajat receives advice from his cousin Bishwanath on how to court Jayanti, showcasing the comedic elements of the film and the contrast between the simple-minded protagonist and his streetsmart relative

- The sequence involving the attempt to secure money from the miserly guardian Bagalcharan for the supposed 'European-style art film', which provides meta-commentary on the film industry itself

- The dramatic confrontation at Dr. Gajanan's clinic where the guardian falls into the clutches of the crooks, marking the shift from romantic comedy to thriller elements

Did You Know?

- P.C. Barua was not only the director but also the lead actor in the film, showcasing his multi-talented abilities in early Indian cinema.

- The film was produced by New Theatres, which was responsible for many landmark films in Indian cinema history during the 1930s and 1940s.

- Rajat Jayanti was made during the period when Bengali cinema was experiencing a creative renaissance, with films addressing social issues while maintaining entertainment value.

- The film's title 'Rajat Jayanti' translates to 'Silver Anniversary' in English, though the plot doesn't appear to directly relate to this theme.

- P.C. Barua was known for his innovative approach to filmmaking, often experimenting with narrative structures and cinematic techniques that were ahead of their time in Indian cinema.

- The film featured a mix of established actors like Pahadi Sanyal and emerging talents, reflecting New Theatres' policy of nurturing new talent while working with experienced performers.

- New Theatres was known for its sophisticated studio system that rivaled Hollywood in its approach to film production during the 1930s.

- The film was released just before World War II, a period that would significantly impact the Indian film industry.

- P.C. Barua had already established his reputation with earlier successes like Devdas (1935) when he made this film.

- The film's plot involving an attempt to make a 'European-style art film' was somewhat meta, reflecting the artistic ambitions of filmmakers of the era.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of Rajat Jayanti is difficult to ascertain due to the limited availability of archival materials from that period. However, films from New Theatres during this era were generally well-received by critics who appreciated the studio's commitment to quality production values and meaningful content. P.C. Barua's reputation as a filmmaker of substance likely ensured that the film received serious critical attention. Modern film historians and critics who have studied the film often note its place in Barua's filmography and its reflection of the cinematic trends of the late 1930s. The film is sometimes mentioned in scholarly works about early Indian cinema as an example of the type of sophisticated entertainment that New Theatres was known for producing. Critics have noted that while the film may not have the lasting impact of Barua's Devdas, it demonstrates his versatility as a filmmaker and his ability to work across different genres within the commercial cinema framework.

What Audiences Thought

The audience reception of Rajat Jayanti in 1939 would have been influenced by several factors, including P.C. Barua's star status as both an actor and director, the reputation of New Theatres as a quality production house, and the popularity of the supporting cast. Bengali audiences of the late 1930s had developed sophisticated tastes and appreciated films that combined entertainment with artistic merit. While specific box office figures or detailed audience reactions are not readily available, the fact that New Theatres continued to produce films and that Barua remained an active filmmaker suggests that films like Rajat Jayanti found their audience. The film's mix of romance, comedy, and drama would have appealed to the broad audience base that cinema was attracting in India during this period. The urban middle class in Calcutta and other Bengali-speaking regions formed the core audience for such films, and their patronage was crucial for the success of productions like Rajat Jayanti.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- European cinema

- Bengali literary traditions

- Theatrical performance styles

- Hollywood romantic comedies of the 1930s

This Film Influenced

- Later Bengali romantic comedies

- Films exploring similar themes of love and deception

- Works by filmmakers influenced by P.C. Barua's style

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

As a film from 1939, Rajat Jayanti faces the preservation challenges common to early Indian cinema. Many films from this period have been lost due to the unstable nature of early film stock and inadequate preservation facilities. The current preservation status of this specific film is not clearly documented in available sources, which suggests it may be a rare or possibly lost film. New Theatres productions were generally better preserved than many other films of the era, but the passage of over 80 years means that even well-maintained films can deteriorate. Film archives in India and internationally may hold copies or fragments of the film, but comprehensive information about its preservation status is not readily available. The National Film Archive of India has been working to preserve and restore early Indian films, but the sheer volume of material and the condition of many prints make this a challenging task.