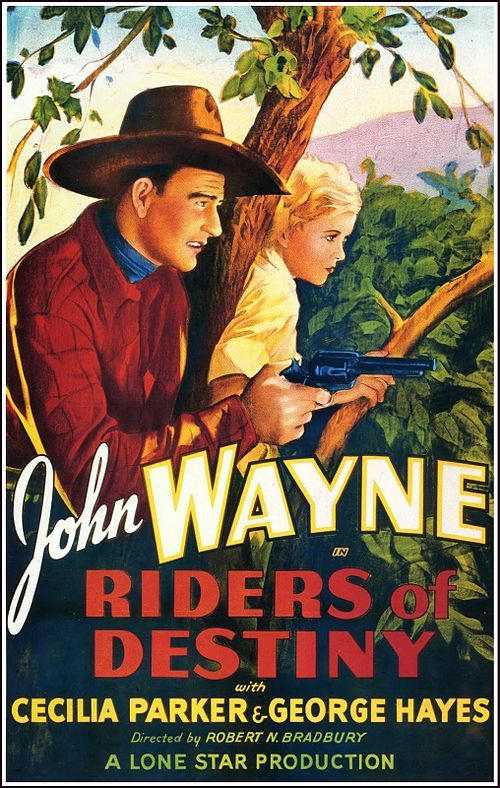

Riders of Destiny

"Singing his way to Justice!"

Plot

Government agent Sandy Saunders (John Wayne) arrives in a drought-stricken western town undercover as a traveling musician to investigate James Kincaid (Forrest Taylor), who has monopolized the local water supply. Kincaid, using his control of the only well in the area, systematically forces neighboring ranchers off their land through exorbitant water prices and violent intimidation. Saunders befriends Fay Denton (Cecilia Parker), whose father is one of Kincaid's primary targets, and begins gathering evidence while maintaining his cover as a mild-mannered singer. As Kincaid's schemes grow more ruthless, including attempts to murder competing ranchers and seize their properties through fraudulent means, Saunders must reveal his true identity to stop the villain. The film culminates in a dramatic confrontation where Saunders, with help from the oppressed ranchers, exposes Kincaid's criminal enterprise and restores water rights to the community while winning Fay's affection.

About the Production

This was one of the first films to showcase John Wayne's singing abilities, though his voice was reportedly dubbed by Smith Ballew. The production was shot in just 6-7 days, typical of the rapid shooting schedules for B Westerns of the era. The water rights theme reflected real concerns in drought-stricken California during the early 1930s. The film featured several dangerous stunts performed by Wayne himself, including horse falls and gunfight sequences.

Historical Background

Released in 1933 during the depths of the Great Depression, 'Riders of Destiny' reflected the era's anxieties about resource control and corporate exploitation. The film's water rights theme resonated strongly with audiences facing drought conditions in the Dust Bowl regions and widespread economic hardship. This was also a transitional period in Hollywood, as the industry fully embraced sound technology after the silent era. The early 1930s saw the rise of B-movie productions designed to fill double bills, with Westerns being particularly popular and cost-effective. The film's release coincided with Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal policies, which included major water projects like the Tennessee Valley Authority, making the water control theme particularly timely. Hollywood was also under pressure from the Hays Code, which was being more strictly enforced, leading to clearer moral distinctions between heroes and villains in films like this one.

Why This Film Matters

While not a major critical success, 'Riders of Destiny' holds significance as one of the films that helped establish John Wayne's screen persona and launched his transition from bit player to leading man. The film contributed to the development of the singing cowboy genre that would become hugely popular in the 1930s, though Wayne himself would quickly move away from musical Westerns. It represents an important example of the B-Western formula that dominated American cinema during the Depression years, providing affordable entertainment to struggling audiences. The film's water rights theme anticipated later environmental Westerns that would address resource management issues. As part of Wayne's Lone Star series, it helped create the template for the lone government agent fighting corruption that would become a recurring motif in Western cinema. The movie also demonstrates how early sound Westerns adapted silent film techniques while incorporating new elements like musical numbers and dialogue-driven storytelling.

Making Of

The production was rushed through in typical B-Western fashion, with principal photography completed in less than a week. John Wayne, still a relatively unknown actor at the time, performed many of his own stunts, including several dangerous horse falls. The film was part of a package deal where Lone Star Productions would deliver multiple low-budget Westerns to Monogram Pictures for distribution. Director Robert N. Bradbury, who had a background in silent films, adapted quickly to sound technology and helped establish many of the visual tropes that would define the Western genre. The singing sequences were particularly challenging, as Wayne was not a trained singer, leading to the decision to dub his voice with Smith Ballew's recordings. The water rights storyline was deliberately chosen as it reflected contemporary concerns about water scarcity during the Dust Bowl era, making the film more relevant to Depression-era audiences.

Visual Style

The cinematography, handled by Archie Stout, utilized the dramatic landscapes of Alabama Hills to create visually striking compositions despite the film's low budget. Stout employed natural lighting to enhance the outdoor sequences and used wide shots to emphasize the isolation and vulnerability of the homesteaders. The camera work during action sequences was notably dynamic for a B-Western, with tracking shots following horse chases and gunfights. The water scenes were filmed to emphasize the preciousness of the resource, using close-ups of water and contrasted shots of parched land. The cinematography helped establish the visual language that would become standard in Westerns, including the use of the landscape as a character in the story. Despite the rapid shooting schedule, Stout managed to create atmospheric shots that elevated the film beyond typical B-movie standards.

Innovations

While not technically innovative, the film demonstrated efficient use of limited resources and rapid production techniques that would become standard for B-Westerns. The production successfully integrated sound recording with location shooting, which was still challenging in the early sound era. The film's use of natural locations rather than studio sets helped create authenticity despite budget constraints. The stunt work and action sequences were choreographed to maximize impact while minimizing risk and cost. The film's efficient editing and pacing set a standard for B-Westerns that would influence the genre for decades. The dubbing of Wayne's singing voice, while not a technical achievement per se, represented an early example of vocal replacement in film that would become more sophisticated in later years.

Music

The film's music was typical of early 1930s Westerns, featuring traditional cowboy songs and original compositions by various uncredited studio musicians. The soundtrack included several musical numbers performed by Wayne's character (dubbed by Smith Ballew), including the title song 'Riders of Destiny' and various ballads performed during the narrative. The musical score was simple but effective, using piano and guitar accompaniment typical of low-budget productions. The sound design emphasized the importance of water through audio cues, with the sound of flowing water used as a recurring motif. The soundtrack helped establish the singing cowboy genre that would dominate Western films in the mid-1930s. The musical interludes, while sometimes interrupting the narrative flow, were popular with audiences of the era and became a signature element of Wayne's early Westerns.

Famous Quotes

I'm Sandy Saunders, government agent. I'm here to see that justice is done.

Water is life, mister. And you're trying to kill this whole valley.

A man who controls the water controls the land, and I won't stand for it.

You can't buy justice, Kincaid, and you can't sell water that belongs to everyone.

This isn't just about ranches anymore. It's about right and wrong.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Saunders arrives in town as a traveling musician, establishing his undercover identity

- The tense confrontation at the water well where Kincaid tries to extort money from desperate ranchers

- The musical performance scene where Saunders sings while secretly gathering information

- The climactic gunfight where Saunders reveals his true identity and leads the ranchers against Kincaid's men

- The final scene where water rights are restored and Saunders wins Fay's heart

Did You Know?

- This was the first of sixteen films John Wayne would make for Lone Star Productions between 1933-1935, establishing his persona as the singing cowboy before he became a major star.

- John Wayne's singing voice was actually dubbed by Smith Ballew, a popular singing cowboy of the era, though Wayne would later sing in his own voice in later films.

- The film was originally titled 'Water Rights' before being changed to the more action-oriented 'Riders of Destiny'.

- Director Robert N. Bradbury was a prolific Western director who made over 100 films and frequently worked with Wayne during this period.

- The water monopoly plot was inspired by real historical water rights disputes in the American West, particularly those involving William Mulholland and Los Angeles water supply.

- This film was one of the earliest to feature Wayne as a government agent rather than a typical cowboy or rancher.

- The movie was filmed on location in Alabama Hills, which would become a classic filming location for hundreds of Westerns.

- Wayne was paid only $2,500 for this film, a fraction of what he would command just a few years later.

- The film's success led to a series of 'Singing Sandy' films, though Wayne reportedly disliked the musical aspects of these early roles.

- Cecilia Parker, who played the female lead, was better known for her role as Marian Hardy in the 'Andy Hardy' film series.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews were generally positive for a B-Western, with Variety noting Wayne's 'appealing screen presence' and the film's 'efficient storytelling.' The Motion Picture Herald praised the action sequences and the timely water rights theme. Modern critics view the film as an important stepping stone in John Wayne's career, though they note its formulaic plot and low production values typical of the era. Film historians recognize it as a representative example of early 1930s B-Westerns and appreciate its role in developing Wayne's star persona. The singing aspects have been criticized as somewhat awkward, particularly given that Wayne's voice was dubbed. Despite its limitations, the film is often cited for its efficient pacing and effective use of limited resources, characteristics that would define the B-Western genre for years to come.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by its target audience of Depression-era moviegoers who appreciated its straightforward morality, action sequences, and timely themes. John Wayne's performance resonated with viewers, helping establish him as a reliable Western hero. The musical elements, while not Wayne's strength, were popular with audiences who enjoyed the singing cowboy trend of the early 1930s. The water rights storyline struck a chord with rural audiences familiar with real-life water disputes and corporate exploitation. The film's modest success at the box office led to multiple sequels and cemented Wayne's status as a B-Western star. Contemporary audience letters to fan magazines frequently praised Wayne's authentic cowboy demeanor and the film's exciting action sequences. The movie developed a cult following among Western enthusiasts and remains popular among classic film collectors and John Wayne completists.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Silent Westerns of the 1920s

- Tom Mix films

- Ken Maynard Westerns

- D.W. Griffith's Western shorts

- Zane Grey stories

- Contemporary newspaper stories about water disputes

This Film Influenced

- 后续的John Wayne Lone Star系列电影

- The Singing Cowboy (1936)

- Riders of the Purple Sage (1931) remakes

- Later water rights Westerns like 'The Big Country' (1958)

- Government agent Westerns like 'The Lone Ranger' series

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in complete form and has been preserved by various film archives. It entered the public domain in the United States due to copyright renewal issues, which has led to its availability on numerous budget DVD releases and streaming platforms. Several restoration efforts have been undertaken to improve the audio and video quality, though the original film elements show some deterioration typical of films from this era. The Library of Congress holds a preservation copy, and the film is part of the collection at the Academy Film Archive. Its public domain status has actually helped ensure its survival through multiple distribution channels.