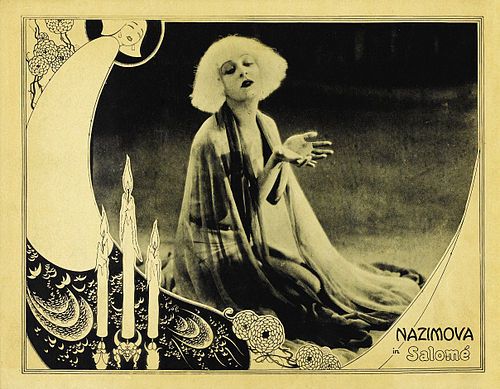

Salomé

"The Most Daring Picture Ever Made!"

Plot

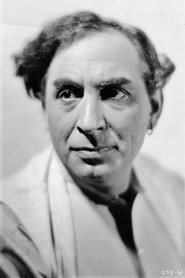

In ancient Judea, Princess Salomé becomes infatuated with the prophet John the Baptist (Jokanaan), who rejects her advances and condemns her mother Herodias's marriage to King Herod. When Herod promises Salomé anything she desires in exchange for performing the Dance of the Seven Veils, she demands the head of John the Baptist on a silver platter. After receiving her gruesome reward, Salomé passionately kisses the dead prophet's lips, horrifying Herod who orders her immediate execution by his soldiers. The film culminates in a tragic tableau of unfulfilled desire and destructive obsession.

About the Production

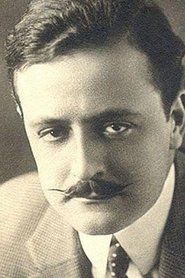

The film was an ambitious artistic project with complete creative control given to Alla Nazimova. The sets and costumes were designed by Natacha Rambova based on Aubrey Beardsley's illustrations for Wilde's play. Production took place over several months with meticulous attention to visual detail. The Dance of the Seven Veils sequence required extensive rehearsal and was considered scandalously erotic for its time. The film faced significant censorship challenges and was banned in several cities.

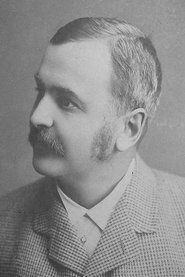

Historical Background

The early 1920s was a period of transition in American cinema, as Hollywood established itself as the global film capital while European art cinema was gaining recognition. The Jazz Age brought new freedoms in artistic expression, though censorship remained powerful. Oscar Wilde's play, written in 1891, had been considered scandalous for decades, making this adaptation particularly daring. The film emerged during the height of the silent era's artistic experimentation, influenced by German Expressionist films like 'The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari' (1920). This was also a time when LGBTQ+ themes, though heavily coded, could find expression in avant-garde art. The film's failure reflected the tension between artistic ambition and commercial expectations in early Hollywood.

Why This Film Matters

Salomé represents a pivotal moment in American cinema as one of the first truly avant-garde art films produced in Hollywood. Its bold visual style influenced subsequent art films and music videos for decades. The film is now recognized as a landmark in queer cinema history, with its all-gay cast and subversive approach to gender and sexuality. Its aesthetic impact can be seen in the work of later directors like Kenneth Anger, Derek Jarman, and even modern music video directors. The film challenged conventional notions of cinema as purely entertainment, proposing it could be high art. Its rediscovery and restoration have cemented its status as a cult classic and an important document of LGBTQ+ representation in early cinema.

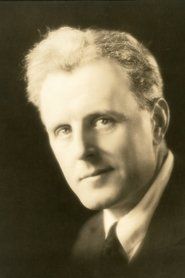

Making Of

The production was a labor of love for Alla Nazimova, who had complete artistic control and invested her own money. She handpicked the cast from actors she had worked with in theater, many of whom were part of her artistic circle. The film's distinctive aesthetic was heavily influenced by European art movements, particularly Art Deco and Expressionism. Natacha Rambova, Nazimova's partner at the time, designed the elaborate sets and costumes based on Beardsley's illustrations. The Dance of the Seven Veils sequence was the most challenging part of production, requiring extensive rehearsals and multiple takes. The film faced constant censorship battles during production and release, with several scenes ordered to be cut or modified. Despite its artistic ambitions, the production was plagued by budget overruns and creative conflicts.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Charles Van Enger was groundbreaking for its dramatic use of shadow and light, creating a stark, theatrical effect that emphasized the film's artificiality. The predominantly white, black, and silver color scheme created a dreamlike, otherworldly atmosphere that was unlike anything else in American cinema at the time. Van Enger employed innovative lighting techniques to create sharp contrasts and geometric patterns, influenced by German Expressionism. The camera work emphasized stylized compositions and theatrical framing, often using unusual angles to enhance the film's surreal quality. The cinematography was crucial in creating the film's distinctive visual language that separated it from conventional Hollywood productions.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was its innovative use of lighting and set design to create a completely stylized visual world. The production pioneered techniques for creating the Art Deco aesthetic on film, using extensive use of mirrors, geometric patterns, and stark lighting. The Dance of the Seven Veils sequence showcased advanced choreography and camera techniques for the period, including multiple camera setups to capture the complex movements. The film also demonstrated innovative approaches to creating visual effects without modern technology, using mirrors, shadows, and clever set design to achieve its surreal atmosphere. The production's use of a limited color palette (black, white, silver) was technically challenging but created a distinctive visual signature that influenced subsequent films.

Music

As a silent film, Salomé would have been accompanied by live musical performances in theaters during its original run. The specific musical selections would have varied by theater, but likely included classical pieces that matched the film's dramatic and exotic tone. The original score has been lost, but modern screenings typically feature newly composed scores or carefully selected classical music that complements the film's avant-garde visuals. Contemporary screenings often use music by composers like Richard Strauss or Gustav Mahler, whose work matches the film's decadent and dramatic atmosphere. Some modern screenings have featured original compositions by contemporary artists specifically created to accompany the restored film.

Famous Quotes

I will kiss your mouth, Jokanaan. I will kiss your mouth.

The mystery of love is greater than the mystery of death.

Ask of me what you will, and I will give it to you, even to the half of my kingdom.

I am chaste, and the blood of your body stains my lips.

The moon is like a virgin seeking a lover.

I have kissed thy mouth, Jokanaan. I have kissed thy mouth.

Memorable Scenes

- The Dance of the Seven Veils: Salomé's seductive and symbolic dance for Herod, where she removes seven veils, each representing a different aspect of her desire and power, culminating in her shocking demand for John the Baptist's head.

- The final kiss: Salomé passionately kissing the severed head of John the Baptist, a shocking and controversial moment that leads to her execution and represents the culmination of her obsessive desire.

- Salomé's first encounter with Jokanaan: The princess's fascination with the imprisoned prophet, establishing the film's central obsession and showcasing the stylized set design.

- Herod's feast: The elaborate banquet scene with its geometric patterns and theatrical staging, establishing the decadent atmosphere of Herod's court.

Did You Know?

- All cast members were reportedly gay or bisexual, leading to it being called 'the queerest film ever made'

- The film's distinctive visual style was based on Aubrey Beardsley's black and white illustrations for Wilde's play

- Nazimova invested her own fortune in the production, which nearly bankrupted her when it failed commercially

- The costumes and sets used only white, black, and silver colors to create a stylized, otherworldly effect

- It was one of the first American art films, influenced by European Expressionist cinema

- The film was considered so scandalous that it was banned in New York City and other major markets

- The Dance of the Seven Veils was choreographed by Theodore Kosloff, a former Ballets Russes dancer

- The film was thought lost for decades before being rediscovered in the 1970s

- Nazimova reportedly said she would rather have one beautiful failure than ten commercial successes

- The film's failure effectively ended Nazimova's career as an independent producer

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics were sharply divided. Some praised the film's artistic ambition and visual innovation, while others condemned it as immoral and pretentious. Variety called it 'a weird picture of artistic pretensions' while The New York Times criticized its 'unpleasant' subject matter. Modern critics have reassessed the film much more favorably, recognizing it as a groundbreaking work of queer cinema and avant-garde filmmaking. The film is now appreciated for its bold visual style, its place in LGBTQ+ film history, and its influence on subsequent art cinema. Critics particularly praise its innovative use of design and its subversive approach to biblical material.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a commercial disaster, alienating mainstream audiences with its avant-garde approach and controversial themes. Many viewers found the stylized presentation confusing and the erotic content shocking. The film's failure nearly ended Nazimova's career as an independent producer and marked a turning point in Hollywood away from such experimental projects. However, it developed a cult following among artistic and queer communities who appreciated its boldness and aesthetic innovation. Over time, its reputation has grown among film enthusiasts and scholars who recognize its historical importance and artistic merit.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Aubrey Beardsley's illustrations for Wilde's play

- German Expressionist cinema

- Art Deco movement

- Symbolist art and literature

- Ballets Russes

- European avant-garde theater

- Oscar Wilde's aesthetic philosophy

This Film Influenced

- Kenneth Anger's experimental films

- Derek Jarman's Sebastiane (1976)

- Federico Fellini's Satyricon (1969)

- Peter Greenaway's The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989)

- Catherine Breillat's Anatomy of Hell (2004)

- David Lynch's artistic sensibilities

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was thought lost for many years but was rediscovered in the 1970s in a private collection. A restored version has been preserved by film archives including the Museum of Modern Art and the UCLA Film and Television Archive. The restoration has preserved the film's unique visual style and historical significance, though some scenes may remain incomplete. The film is now available in restored versions that showcase its original artistic vision.