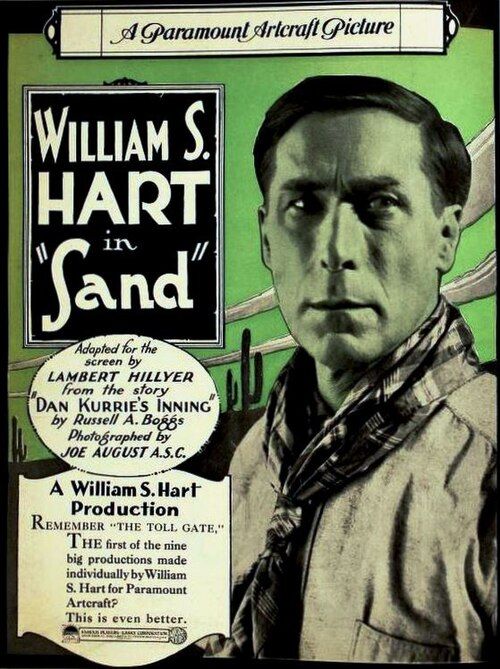

Sand

"A Man's Honor in the Lawless West!"

Plot

Dan Kurrie, a dedicated railroad station agent, finds his life upended when he's unjustly fired by Joseph Garber, his romantic rival for the affections of Margaret. Dismissed under false pretenses and disbelieved by the woman he loves, Kurrie's reputation is shattered and his future uncertain. Determined to clear his name and win back Margaret's trust, Kurrie embarks on a dangerous investigation into a series of train robberies plaguing the railroad. As he delves deeper into the criminal underworld, Kurrie discovers that Garber himself may be connected to the gang of bandits terrorizing the region. Through a series of thrilling confrontations and narrow escapes, Kurrie must use his knowledge of the railroad and his frontier skills to expose the true culprits and restore his honor. The film culminates in a dramatic showdown where Kurrie faces off against the bandits, proving his innocence and heroism while winning back Margaret's love.

About the Production

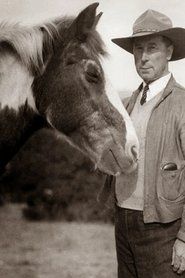

Sand was one of William S. Hart's final major starring roles before his career began to wane in the early 1920s. The film was shot on location in California's rugged terrain, taking advantage of the natural desert landscapes that Hart preferred over studio sets. Hart, known for his authenticity in Westerns, insisted on using real railroad equipment and authentic period costumes. The production faced challenges due to the remote filming locations, requiring cast and crew to endure harsh weather conditions. Lambert Hillyer, who had directed several of Hart's previous films, employed his signature style of blending action with emotional character development.

Historical Background

Sand was produced during a pivotal period in American cinema history. The year 1920 marked the beginning of the Roaring Twenties, a time of significant social and cultural change following World War I. The film industry was transitioning from short films to feature-length productions, with Westerns remaining one of the most popular genres. William S. Hart represented the older, more realistic school of Western filmmaking, which emphasized authenticity and moral complexity over the romanticized approach that would later dominate the genre. The railroad theme in Sand reflected America's ongoing fascination with westward expansion and the taming of the frontier. The film was released just before Hollywood began consolidating into the studio system that would dominate the decade. 1920 also saw the rise of new censorship pressures with the formation of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, though Hart's films generally avoided controversy due to their moralistic approach.

Why This Film Matters

Sand represents an important transitional work in the evolution of the Western genre. William S. Hart's portrayal of the wronged hero seeking justice helped establish the archetype of the noble Western protagonist who operates outside conventional authority but maintains a strict moral code. The film's emphasis on realistic frontier life, as opposed to the mythologized West that would later become popular, offers valuable insight into early 20th-century American attitudes toward progress, civilization, and individualism. Hart's approach to Western storytelling influenced subsequent directors, including John Ford, who admired Hart's commitment to authenticity. The railroad theme in Sand also reflects the historical importance of rail expansion in American consciousness, symbolizing both progress and the destruction of traditional ways of life. The film's survival and preservation have made it an important document of silent-era filmmaking techniques and Hart's contribution to American cinema.

Making Of

The making of Sand reflected William S. Hart's meticulous approach to Western filmmaking. Hart, who had been a real cowboy and understood frontier life firsthand, insisted on historical accuracy in every aspect of production. He personally selected the filming locations, favoring the authentic desert landscapes of California over studio backlots. The railroad sequences were particularly challenging, requiring coordination with actual railroad companies to use their tracks and equipment. Hart and director Lambert Hillyer developed a close working relationship, with Hart often contributing to script development and character motivation. Mary Thurman, playing the female lead, had to adapt to Hart's intense method of acting, which emphasized subtlety and emotional truth over theatrical gestures. The film's production schedule was compressed to take advantage of optimal lighting conditions in the desert, leading to long, grueling days for cast and crew. Hart's commitment to authenticity extended to the costumes, which were often actual period pieces he had collected over the years.

Visual Style

The cinematography in Sand, credited to Joseph H. August, showcases the visual sophistication of late silent-era filmmaking. August utilized natural desert light to create stark contrasts between light and shadow, emphasizing the harshness of the frontier environment. The railroad sequences feature impressive tracking shots that follow the movement of trains, demonstrating advanced camera techniques for the period. August employed wide shots to establish the vastness of the landscape, then moved to intimate close-ups for emotional moments, creating a visual rhythm that enhances the storytelling. The film's visual style emphasizes realism over romanticism, with compositions that highlight the isolation of characters in the wilderness. August's work on Sand demonstrates his mastery of location photography, particularly in capturing the textures of sand, rock, and weathered wood that define the film's authentic Western atmosphere.

Innovations

Sand demonstrated several technical achievements for its time, particularly in its use of location photography and action sequences. The film's railroad scenes required innovative camera mounting techniques to capture moving trains from various angles. The production team developed specialized equipment to film from moving platforms, creating dynamic shots that put audiences in the middle of the action. The desert location work presented challenges in terms of equipment transport and film stock protection from heat and sand, requiring careful planning and execution. The film's editing, particularly during the action sequences, shows sophisticated understanding of rhythm and pacing for maintaining audience engagement. The use of natural lighting in desert environments demonstrated advanced understanding of exposure and contrast control in challenging conditions. These technical elements contributed to the film's realistic feel and helped establish new standards for location-based Western filmmaking.

Music

As a silent film, Sand would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have been compiled from classical pieces and popular songs of the era, adapted to match the film's mood and action sequences. For the dramatic scenes, theater organists or small orchestras would have used melancholic compositions to underscore Dan Kurrie's emotional turmoil. The action sequences, particularly the train robberies and chase scenes, would have been accompanied by more energetic, rhythmic music to heighten tension. Modern restorations of Sand have been scored by contemporary silent film composers who attempt to recreate the musical experience of the 1920s while using modern recording techniques. The original cue sheets, if they exist, would have provided specific musical suggestions for theater musicians, though these documents are often lost for films of this period.

Famous Quotes

"A man's name is all he has in this country, and I won't see mine dragged through the dirt by the likes of you!" - Dan Kurrie

"The desert doesn't lie, and neither do I when I say those trains are being robbed by someone who knows every inch of this track." - Dan Kurrie

"You can fire me from my job, but you can't fire me from being a man who knows right from wrong." - Dan Kurrie

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic confrontation scene where Dan Kurrie confronts Joseph Garber after being fired, with Hart's intense performance conveying both anger and dignity. The spectacular train robbery sequence featuring real vintage railroad equipment and dangerous stunt work performed by the actors. The final showdown in the desert where Kurrie exposes the gang of bandits, filmed during golden hour for maximum visual impact. The emotional reunion scene between Kurrie and Margaret after his name is cleared, showcasing the subtlety of silent-era acting at its best.

Did You Know?

- William S. Hart was 56 years old when he made this film, playing a much younger character, which was common for leading men of the silent era.

- The film features authentic 19th-century railroad equipment that Hart had collected for his productions.

- Sand was one of the last films Hart made with Artcraft Pictures before he moved to Paramount.

- Director Lambert Hillyer collaborated with Hart on multiple films, including 'The Toll Gate' (1920) and 'Three Word Brand' (1921).

- Mary Thurman, who played Margaret, was a former Mack Sennett bathing beauty who transitioned to dramatic roles.

- The film's title 'Sand' refers to both the desert setting and the shifting nature of trust and loyalty in the story.

- G. Raymond Nye, who played the villain Joseph Garber, frequently appeared as a heavy in Hart's films.

- The train robbery sequences were performed without stunt doubles, with Hart doing many of his own dangerous riding scenes.

- Sand was released during the height of Hart's popularity but came just before Western tastes began to shift toward more romanticized portrayals.

- The film's original negative was believed lost for decades before a print was discovered in the 1970s in a European archive.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Sand for its authenticity and Hart's powerful performance. The Motion Picture News noted that 'Hart once again proves his mastery of the Western genre, bringing depth and humanity to what could be a routine tale.' Variety highlighted the film's spectacular railroad sequences and praised Lambert Hillyer's direction for maintaining tension throughout. Modern critics have reassessed Sand as a significant example of Hart's mature work, with film historian Kevin Brownlow calling it 'one of Hart's most emotionally complex Westerns.' The film is now appreciated for its realistic depiction of frontier life and its avoidance of the romantic clichés that would later dominate the genre. Critics have also noted the film's impressive location photography and its effective use of the desert landscape as a character in the story.

What Audiences Thought

Sand was well-received by audiences in 1920, particularly among Hart's loyal fan base. The film performed solidly at the box office, though it didn't achieve the blockbuster success of some of Hart's earlier films like 'Hell's Hinges' (1916) or 'The Toll Gate' (1920). Audience response letters published in trade papers praised Hart's performance and the film's exciting action sequences. The railroad robbery scenes were especially popular with viewers, who appreciated their realism and danger. Modern audiences who have had the opportunity to see Sand at film festivals or in archival screenings have responded positively to its straightforward storytelling and Hart's charismatic performance. The film's themes of wrongful accusation and redemption continue to resonate with contemporary viewers, demonstrating the timelessness of Hart's approach to Western storytelling.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Great Train Robbery (1903)

- Hell's Hinges (1916)

- Stagecoach (1939) - influenced by Hart's realistic approach

This Film Influenced

- The Iron Horse (1924)

- Union Pacific (1939)

- Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) - railroad themes

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Sand was considered a lost film for several decades before a complete 35mm print was discovered in the Czechoslovakian Film Archive in the 1970s. The discovered print, though showing some signs of deterioration, was remarkably complete. The film has since been preserved by the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. A restored version was released on DVD as part of the William S. Hart collection, featuring new musical scores and improved picture quality. The preservation efforts have ensured that this important example of Hart's work remains accessible to modern audiences and scholars of silent cinema.